Baniwa

- Self-denomination

- Walimanai

- Where they are How many

- AM 7145 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Colombia 7000 (, 2000)

- Venezuela 3501 (XIV Censo Nacional de Poblacion y Viviendas, 2011)

- Linguistic family

- Aruak

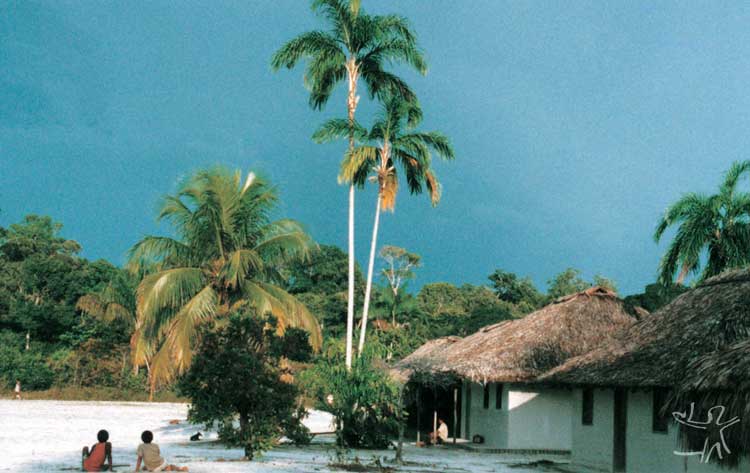

The Baniwa live on the borders of Brazil with Colombia and Venezuela, in villages located on the banks of the Içana River and its tributaries the Cuiari, Aiari and Cubate, as well as in communities on the Upper Rio Negro/Guainía and in the urban centers of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Santa Isabel and Barcelos (AM). The Kuripako, who speak a dialect of the Baniwa language and are kin of the Baniwa, live in Colombia and on the upper Içana (Brazil). Both groups are highly skilled in the manufacture of arumã (aririte) basketry, an age-old art that was taught to them by their creator heroes and which is being commercialized today in Brazilian markets.

Recently, they have also become outstanding for their active participation in the indigenous movement in the region. This movement includes a cultural complex of 22 different indigenous groups who are articulated through a network of trade and are very similar in their social organization, material cultural, and worldview.

Names and languages

Since colonial times, the name Baniwa has been used to refer to all peoples who speak Arawakan languages who live along the Içana River and its tributaries. It should be emphasized, however, that the name is not a self-designation. It is a generic name used by these Indians to represent themselves in multiethnic contexts or to the non-indigenous world. The term “Walimanai” means "the other new generations who will be born" and is a collective self-designation used in contrast with the ancestors, “Waferinaipe”, the ancestors who created and prepared the world for the living, their descendants, the Walimanai of today. The Baniwa more frequently use as collective self-designations the names of their phratries such as Hohodene, Walipere-dakenai or Dzauinai.

The Kuripako, who live in Colombia and on the upper Içana (Brazil), are related to the Baniwa and speak a dialect of the Baniwa language, although they do not identify themselves as a Baniwa subgroup. The Kuripako live in communities along the Guainía River (the name for the Rio Negro outside of Brazil, above the junction with the Cassiaquiare Canal) and its tributaries, and the upper Içana. In Venezuela, they are called Wakuenai, a collective self-designation that means “those of our language", and live in communities along the Guainía River and its tributaries. There is another group, called Baniva, who speak a distinct Arawakan language, and who live in the village of Marôa, on the Guainía.Despite their having a specific identity, the Kuripako are very similar to the Baniwa, such that the information relative to the Baniwa in most items of this section can, in large part, be extended to the Kuripako.

History of occupation

Like their neighbors on the Uaupés River, the Baniwa presently live on the banks of the main rivers, but they say that their ancestors did not live so close to the rivers and built their malocas (longhouses) generally at the headwaters of the main feeder streams. Even today, the Baniwa indicate ancient dwelling places which are presently uninhabited. Many of the elders say that they have even seen houseposts, the remains of ancient malocas, still standing in some of these places. In the region of the upper Içana, there was an ancient and important maloca at the headwaters of the Pamari stream, which is an area traditionally occupied by the Walipere-dakenai (or Siuci, in língua geral, the trade language of the area, which means “descendants or grandchildren of the five stars", the constellation of the Pleiades) phratry. The Walipere-dakenai say that this maloca was the dwelling place of their first leader, Vetutali (or Wetsúdali), a powerful warrior ancestor of all the present-day Walipere-dakenai. They say that, in the time of slavery, Vetutali and many other Baniwa were taken as slaves by the Portuguese. When the boat that took prisoners was on its way down the Rio Negro, Vetutali and a Hohodene companion threw themselves into the river and succeeded in escaping, then returning to the Içana.

Like the Walipere-dakenai, the Hohodene tell of a warrior ancestor called Keruaminali, who was also taken prisoner by the whites and stayed for some time in Barcelos on the lower Rio Negro until he succeeded in fleeing and returning to the Içana. Like Vetutali, Keruaminali, on returning to his land, went to live at the headwaters of a feeder stream, the Uaraná, tributary of the upper Aiari River. The Walipere-dakenai then came to occupy a large area of lands, from the mouth of the Pamari on the Içana River to the south, to the area around the present-day village of Tamanduá to the west. To the north, the limits of this territory reached the Cuiary River, in Colombia. The Hohodene settled in the interfluvial region of the Içana and Aiari rivers, more precisely at the headwaters of the Quiari, Uirauassu and Uaraná streams. Some Walipere-dakenai went to live near the Hohodene and since then there have been numerous marriages between the two groups. According to Hohodene and Walipere-dakenai traditions, the flight and return of these two leaders marked an important moment in their history, for it was when the Içana came to be reinhabited after a period of nearly total abandonment resulting from the enslavement and descents (descimentos, relocation) of the indigenous population.

Over time and due to the influence of missionaries, the military and white merchants, the Baniwa began progressively moving away from the sites of their ancient malocas in the interior of the forest to the banks of the Içana. The Baniwa population grew and the Walipere-dakenai, for example, spread over the whole Içana river region. The Hohodene built their villages further down the Quiari stream and eventually occupied the entire Aiari River region. There are Baniwa communities who have settled in more recent times even on the Rio Negro, below São Gabriel da Cachoeira and a number of Walipere-dakenai and Hohodene are living in the vicinity of Barcelos. Even so, the area described above continues to be considered their territory par excelence and is so recognized by other Baniwa groups.

Location and population

The hydrographic basin of the Içana River has its sources in Colombia, but after a short distance it defines the border with Brazil, then flowing directly into Brazilian territory in a southwesterly direction. The Içana is about 696 kilometers in length. From its headwaters to the Colombia/Brazil border it flows for 76 kilometers. It forms the border with Colombia for another 110 kilometers and from there it flows another 510 kilometers until it joins the Rio Negro. In Brazilian territory, the river has 19 rapids.

At its sources, the Içana is a whitewater river and begins to change its color to reddish and then becomes a blackwater river after receiving the waters from feeder streams such as the Iauareté (or Iauaiali, as the Baniwa and Kuripako call it) and others. The principal tributaries of the Içana are the Aiari, Cuiari, Piraiauara and Cubate rivers, all of these being blackwater rivers. The Içana flows into the Rio Negro above the mouth of the Uaupés River.

The Baniwa in Brazil are distributed in 93 settlements, between villages and smaller sites; out of a total approximate population in the year 2000 of 15 thousand individuals, around 4,026 live in Brazil. The villages on the Brazilian side are located on the mid- and lower Içana and on the Cubate, Cuiari and Aiari rivers. The Baniwa also live in communities along the upper Rio Negro, and in the cities of São Gabriel, Santa Isabel and Barcelos. The Kuripako are found almost exclusively on the upper Içana and, in Brazil, total approximately 1,115 people.

There has been a Salesian mission at Assunção on the Içana since 1952. There are four other mission bases along the Içana River, all of them maintained by the New Tribes Mission of Brazil: Boa Vista, located at the mouth of the river; Tunuí, at a rapids of the same name on the middle Içana; São Joaquim and Jerusalém, on the upper Içana (among the Kuripako). In São Joaquim, there also is a Frontier Platoon of the Army.

History of contact

The first documented reference known about the Baniwa mentions their alliance with the Caverre (a Piapoco group of the Guaviare river), at the beginning of the 18th Century, against Karib warriors engaged in obtaining slaves for the Spaniards. The Baniwa are also mentioned in Portuguese sources of the same period as having been brought as slaves, probably by the Manao people of the middle Rio Negro, from the upper Rio Negro to the Fort of Barra at the mouth of the river. There are records in the Public Archives of Belém do Pará that indicate that the Baniwa were captured in great numbers between the years 1740 and 1755, and sent to Belém. It is also possible that they may have absorbed renegades from other indigenous peoples into their population during the wars for the capture of slaves in the first half of the 18th Century.

With the intensification of colonization on the Rio Negro, in the second half of the 18th Century, sicknesses introduced by the Whites began to spread death among the Baniwa. Although it is impossible to estimate losses, the records mention several major epidemics of measles and smallpox in the 1740s and 1780s. Their effects, coupled with the generally deteriorating living conditions and supplies of merchandise guaranteed by the Whites led many Baniwa to leave their homelands and descend the Rio Negro to settle in the newly-founded colonial towns of the lower Rio Negro. There they worked for the Whites in agriculture, in the Royal Service and in the gathering of forest products. When it was not possible to convince those Baniwa who wished to remain on their lands, to descend, the Portuguese military – at times allied with other Arawakan peoples, such as the Baré – resorted to force. There are various cases on record of “descents” in the 1780s which basically consisted of armed attacks on Baniwa villages, which the Indians resisted, and which earned them the reputation of being "warlike".

The Indians’ stays in colonial towns were more often than not temporary as many saw what they had gotten into and quickly withdrew. Colonial towns of the late 18th cnetury were chronically plagued by diseases and suffered from depopulation and frequent desertions of Indians descended from the upper regions. The Baniwa, who never seemed to have been settled anywhere else than on the lower Rio Negro, were among those who often deserted. Those who stayed were assimilated into the white, or caboclo, population.

By the end of the 18th century, the Portuguese and Spanish colonies had fallen into a period of disorganization which enabled native peoples to recover, in part, from the losses they had suffered and to reorganize. The Baniwa had barely survived by the end of the 18th century but, with the disorganization of the colonies, they returned to their homelands on the Içana and sought to rebuild their society. But the respite was brief for, by the 1830s, traders and merchants began to work permanently on the upper Rio Negro. Many of these were caboclos who lived for long periods of time in Indian villages and served as useful allies to the military at the forts of São Gabriel and Marabitanas in corraling Indian labor for the Royal Service, commercial industry and extraction of forest products, or to work as domestic servants in elite family households of Manaus. Whatever business the military needed done, traders could be engaged to do it for them in return for protection of their trade. Numerous cases may be found in the records of military who conducted their own trade or became full-time traders once they’d left military service. The naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace, for example mentions cases of former soldiers turned merchants on the Içana who continued to receive the sponsorship and protection of the military commander at Marabitanas to take Baniwa Indians to work for him in gathering salsaparilla.

Through their skillful manipulation of the threat of force, distribution of trade goods and cachaça, and manipulation of local chiefs, the merchants and military maintained an oppressive system of labor exploitation in operation for years, doing what they could to increase production and revenues and, at the same time, their own wealth. Indigenist policy of the state government in Manaus in the early 1850s seemed to grant legitimacy to this system, for the records amply testify to the unchecked abuses of authority by local officials on the upper Rio Negro.

The Baniwa bore a great deal of the brunt of this system although, where they could, they kept their distance from the Whites. Growing popular resistance to white domination among Indians of the upper Rio Negro culminated in a series of millenarian movements among the Baniwa, Tukano, and Warekena from 1857 on.

The first movement was led by Venancio Anizetto Kamiko, a Baniwa of the Dzauinai phratry, from the upper Guainia, the most famous of all the prophets from the mid-19th Century until his death in 1903. According to the written sources, he organized large festivals among the communities of the Içana in which he preached, in the presence of a cross. He suffered from catalepsy and, during his attacks, he said that he died and went to heaven where he communicated with God, who gave him orders to pardon the debts of the Indians to the white merchants. He attracted a large following who believed in his powers and that he was an emissary of God. Then came the moment when he prophesied the destruction of the world by a great fire from wich only the Baniwa of the Içana who danced in circles, day and night, singing the music of the rituals of initiation, would be saved. According to the narratives that the Baniwa and other peoples of the upper Rio Negro tell even today, Kamiko preached the strict observance of fasts, cerimonial chants, and the total avoidance of social and economic relations with the Whites (especially, the military), as the means to obtain salvation in the promised paradise. The narratives also relate that he preached against witchcraft and sorcery in Baniwa communities, for he sought to implant a new moral order amongst his followers.

Other prophetic leaders, disciples of Kamiko – such as Alexandre, who preached more on the Uaupés river -, spoke of the inversion of the existing socio-economic order, after which the the Whites would serve the Indians in compensation for the time that the Indians had been dominated by the Whites. All narratives relating to this time are clear in affirming that the messiahs set their power and knowledge against the repression of the Whites and that the key to indigenous survival was to be found in autonomy in relation to the devastating influences of contact.

With the military repression of these movements, the messiahs and their followers had no choice but to retreat into inaccessible areas of refuge; many refused to obey the military’s orders to return to riverine settlements, or only did so with reluctance. The messiahs, however, continued to have great influence throughout the latter half of the 19th century, practicing their cures and providing counsel to the Indians who came to visit them from throughout the region.

By the 1870s, the rubber boom had reached the upper Rio Negro, introducing a more intense system of labor exploitation than the Baniwa had known before. Local bosses working for large export firms gained control over the lands and resources of vast areas of the region which they exploited with their armies of rubber-gatherers. The Içana and its tributaries came under the control of a Spanish-born merchant, Germano Garrido y Otero, who, with his brothers and sons literally controlled the region for over 50 years. Garrido set up a sort of feudal system in the region, with hundreds of Baniwa at his service. With considerable skill, he placed his sons and allies as “Delegates of the Indians” in strategic villages, manipulated social relations of compadrio and marriage with the Indians, maintained a regular supply of goods and controlled commerce on the Içana, and held in permanent debt a sufficient number of Indians to serve as examples to others.

While the Baniwa remember Garrido as the most influential patrão of this time, they also remember the terror and persecution from the military at the Fort of Cucuy who, at the turn of the century, hunted the Indians of the Içana and Uaupés to serve as rowers, invaded longhouses, stole commercial products from the Indians, cheated Indian laborers, and conducted trade in contraband as well. Like the Colombian patrões of the Uaupés at this time, these military were feared, as evidenced by reports of whole villages seeking refuge in inaccessible areas, or taking to immediate flight at the appearance of the white man.

While the creation of S.P.I. posts from 1919 on, and Salesian missions from 1914 on, helped to control the situation in the region, they had minimal effects, at least initially, on the Içana. Testimony of Baniwa experiences with patrões from the 1930s on confirms that the extractivist regime continued in operation, intensifying during the Second World War, and that Baniwa life-histories in large measure were defined by their work for patrões.

Baniwa narratives about this time are full of episodes of violence, flight and terror that marked their lives. Nevertheless, in the 1920s and 30s, another prophetic figure, the son of Kamiko called Uétsu (of the Adzanene sib), arose, and, like his father, waged a campaign against witches in Baniwa communities in order to re-establish moral order and happiness. Narratives tell how Uétsu had powers just like those of his father, led a great movement with festivals, and consolidated a group of disciples who considered him like a "king". He communicated with the souls of the dead and with God, who advised him about events that were about to happen. He was eventually killed by his enemies; but, the descendants of his disciples continue even today to visit his tomb to ask for his protection from witchcraft and evil omens.

Shortly after the death of Uétsu, in the late 1940s, the North American evangelist Sophie Muller, of the New Tribes Mission, began her work of evangelizing the Kuripako of Colombia, extending this to the Içana in 1949-50. Initially at least, Baniwa conversion to evangelism had all the makings of a millenarian movement - many Baniwa considered Muller a messiah and flocked to hear her message and convert to the new faith. At about the same time, Salesian priests began working on the Içana, producing a division between evangelical, or crente, and Catholic communities which has lasted until the present day.

Over the last two decades, Baniwa communities have confronted a new level of white penetration, representing the interests of national security and corporate mining. Beginning with the announcement in the 1970s that the Northern Perimeter highway would cut through their lands, followed soon after by the building of airstrips and, since 1986, the implantation of the Northern Channel Project, top-level government commissions from Brasília have visited the area with frequency, introducing a qualitatively different dimension of government interest in, and control over, the Baniwas’ future. Official indigenist policy of assimilation, supported at least initially by the Salesians and until the present day by the military, has also put a new strain on Baniwa defense of their territory and culture. In the 1980s, gold-panners, followed by mining companies, often with the protection of the Federal Police have invaded Baniwa territory, causing disruption and various instances of violence.

In the face of these recent invasions, the Baniwa initially re-affirmed their historical stance of autonomy from the Whites, seeking control over their mineral resources and the removal of all gold-panners from their lands. The constant pressure exercised by mining companies - such as Paranapanema and GOLDMAZON - supported by repression from Federal Police agents produced grave internal divisions among Baniwa communities: some took the side of the companies, others against. At the same time, the Northern Channel Project threatened to diminish drastically both the size of Baniwa territory and their capacity to impede the invasions.

In view of these circumstances, various leaders emerged to organize the resistance in a more effective way. The active participation of these leaders in the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the upper Rio Negro (F.O.I.R.N.), founded in 1988 - a pan-indigenous political organization - and in party politics, and the recent creation of various local associations of Baniwa communities – such as the Indigenous Organization of the Içana Basin (OIBI) and the Association of Indigenous Communities of the Aiari River (ACIRA) -, represents a new configuration of political articulations that is defining the specific and concrete demands of Baniwa communities.

For more on the process of demarcation of Indigenous Lands and the creation of the FOIRN, see the section on “Demarcation of Indigenous Lands and Indigenous Organizations” in the Etnias do Rio Negro entry .

Social and political organization

Baniwa society today is subdivided into various phratries or groups of sibs – such as the Hohodene, the Walipere-dakenai and the Dzauinai – traditionally located on determined parts of the rivers of the region. The phratries are exogamous (that is, their members do not marry amongst themselves) and, in the past, there is evidence that they were organized in linguistic groups corresponding to the dialects of the Baniwa language – such as kuripako, karom and others -, similar to what occurs in some areas of the Tukanoan peoples. But today, due to dislocations and historical migrations, probably the only linguistic groups that continue to maintain their identity are the Kuripako of Colombia, whose name refers to a dialect (Kuri- = negative; -pako = they speak) and the Wakuenai of Venezuela (Waku- = our speech; -enai = collective; or "Those of our language").

According to the tradition of the Hohodene phratry, they are the highest-ranking sib of a group of five sibs - the Maulieni, the Mulé dakenai, the Hohodene, the Adzanene, and “the younger brothers of the Adzanene" (Alidali dakenai), whose ancestors were “born" at the same time in the epoch of creation. It is notable in this phratry the sibs’ sentiments of identity based on a common place of mythical emergence and territory. In the myth of the creation of this phratry, there is evidence that there exists an hierarchical relation associated with cerimonial roles among the sibs: the first sib born was the Maulieni, the “grandfathers of the Hohodene”, also called "maaku", or servant sib, who cleaned the ground where the other sibs would be born; the second sib to be born was the Mulé-dakenai, the elder brothers of the Hohodene and a chiefly sib, who arranged the benches for everyone to sit in the cerimonial room; the third group to be born, when the sun was high, was the Hohodene, the “children of the Sun", a warrior group, and the highest ranking group in the hierarchy for they were born in the middle of the order; after them, the Adzanene and their younger brothers were born.

Each phratry thus consists of at least four or five patri-sibs ordered according to the emergence of a group of mythical ancestral brothers, from the oldest to the youngest. The name of the phratry is the same as the sib which is considered the highest in the hierarchy of brothers. For example, the Tuke-dakenai, Kutherueni, and approximately four other sibs – not all of whom have living respresentatives today - all belong to the phratry of the Walipere-dakenai, which is considered the highest ranked sib in the hierarchy, though they are not the eldest brother sib; the model for conceptualizing the relations among the sibs is the cluster of stars comprising the Pleiades constellation. The Walipere-dakenai are considered to be the “head” of the constellation. The Dzauinai phratry consists of the Kadapolithana, the Liedawiene, the Dzauinai, and a number of others, the model for which is the body of a jaguar, for which the Dzauinai (meaning people of the jaguar) likewise represent the head.

The Baniwa trace descent through the paternal line. The core of local communities consists of a group of brothers who are descendants of the founding family, along with their families. The ties among brothers form the basis of a system of hierarchical order according to relative age. The social and political importance of the order, however, is subject to local variations in practice. On the Aiary, for example, it is the eldest brother of the group of ‘brother’ descendants of the founding family (including parallel cousins) who is traditionally the chief (thalikana) of the community, while among Dzauinai communities of the Guainía, it is the youngest brother who is attributed this function.

Communities of the same sib are likewise ordered in terms of a hierarchy of ‘brothers’, descendants of the sons of the founding ancestor of the sib. The Hohodene of Uapui Cachoeira, for example, consider that they are the eldest brothers of all Hohodene communities, although they say that in the past, there was another descent group – which today no longer lives on the Aiary - which was their elder brothers. This internal ordering of the sibs according to a hierarchy among local communities is mostly reflected in the use of kinship terms, and it is evidently subject to disputes as to relative position in the hierarchy.

Marriage rules among the Baniwa prescribe phratric exogamy and express a preference for marriage among patrilateral cross-cousins. Direct exchange of sisters frequently occurs among preferred affinal lineages and sibs and, in some cases, a preference is expressed for marriages between people of sibs pertaining to different phratries but who are of similar hierarchical positions. Marriages are generally monogamous (although there still are cases of polygamy) and are arranged by the parents of the couple.

Virilocality is the predominant residence pattern; however, the rule of brideservice frequently produces situations of temporary or permanent uxorilocality. Communities thus include affines and even may evolve into multi-phratric or multi-sib communities, or even, in cases of longtime exchange partners, moieties. The intolerance of the evangelical missionaries has considerably modified residence patterns and marriage between cross-cousins, thus contributing to situations of permanent uxorilocality.

The leaders of the communities, or capitães, vary in terms of their exercise of authority, but all must have the approval of the community – principally the group of elders – in any decision they take, and the expectation is that the capitães act as intermediaries in internal affairs and as interlocutors in relations with outsiders. Besides that, they organize collective work parties, preside over community meetings and religious activities, distribute community production, and reinforce the patterns of community behavior. Should a capitão not comply with his obligations, the elders of the community may decide by consensus in favor of his substitution. In evangelical communities, the structure of religious authority is superimposed onto the traditional hierarchy of the elders, and may even reinforce it. With the creation of new political associations since the 1990s, various young leaders have emerged who are connected to the regional indigenous movement. These young leaders, however, remain under the control and censure of the traditional political authority of their communities.

Ecology and subsistence

The two basic subsistence activities of the Baniwa are agriculture and fishing, which have equal and complementary cultural and economic importance. Baniwa knowledge of the forests is extensive. Every man knows where to find the best lands for gardening, where to look for fruits, and where to hunt game. In the Walipere-dakenai territory there are many areas of terra firme which means that land for new gardens is found in abundance. But, there are no flooded areas on their lands, in contrast with the lands of their affines, the Dzauinai who live downriver in a region of many lakes. The Dzauinai of the community of Juivitera, for their part, do not have terra firme to plant gardens and they only have one small island located in the middle of a great flooded area in the mid-Içana. They say that this island was “made” by the Walipere-dakenai, who brought earth for them in many journeys by canoe. At that time, the Walipere-dakenai women who married the Dzauinai men suffered because they did not have manioc to make beiju in sufficient quantity, and it was for that reason that they decided to make a place where their affines could plant gardens.

Near their ancient dwelling places, the Baniwa also indicate the existence of patches of black earth which, when possible, are used for gardens because of their excellent productivity. There also are old areas of brushwood, from which they obtain great quantities of plant remedies. Besides the major ecological divisions - terra firme (not flooded), campinarana (bush forest with hard and stiff leaves, in sandy soils) and igapó (forest flooded over most of the year) - the Baniwa demonstrate a refined and detailed knowledge of the differences in the forests of their area. This is evident, for example, in the narratives of origin of the various Baniwa groups. In one version of these narratives, it is said that when the Creator/Transformer Nhiãperikuli took the ancestral couple of each one of the phratries (Walipere-dakenai, Hohodene, Dzauinai, Adzanene, etc.) out of the holes of the rapids of Hipana on the Aiari river, each of them went to live in a determined place, in the middle of the forest, where there was a cluster of patauá fruit trees.

In fact, the manner in which the Baniwa perceive their environment not only includes the macrodivisions mentioned above based on ecological studies, but also demonstrates a refinement within these categories. These “scientific” units are given specific names in the Baniwa language: hamariene (open fields, or savannah), édzaua (terra firme) and arapê (flooded land), although they do not specifically designate the type of vegetation or soil, for they refer more precisely to the type of landscape, associated with a type of vegetation and soil. For example, the term hamariene designates a “clear” environment, a marked characteristic of savannah formations, for the forest is more open in comparison with terra firme.

Besides that, there are terms in the Baniwa language to designate specific types of vegetation, which refer to an enormous gamut of identified variations within the above cited categories. This is a system of classification based on the perception of the dominance of different species in specific parts of the forest. For example: the term punamarimã is comprised of punama (= patauá) and rimã (= concentration of), which can be translated as “area of patauá", or even "patauazal". According to the Baniwa, the punamarimã consists of a specific kind of vegetation that occurs in the interior of the campinarana forest, that is, the presence of a dominant species indicates in this system a specific typological sub-unit. This classificatory resource is employed in a generalized way, such that all the different parts of the forests, in terra firme, campinarana or igapó, have specific names.

The Baniwa classify the terra firme forest soils according to a gradient of colors that varies from yellow to black. Black soils occur in various points of their territory, as is the case of the mukulirimã type, which is one of the best types of earth, even for planting corn. They consider precisely the dark coloring and gross texture of the earth in their choice for the clearing of a garden. Another criteria used by their ancestors is the taste of the soil: the more bitter the soil, the more inappropriate for a garden (comparing with the taste of castanha, brazilnuts). As for campinarana, they say that in general the soil is sandy, except for the types called uaparimada, mapuruti and kuiaperimã which are clearly darker, and are more useful for the opening of small gardens.

While fishing is an activity that occurs throughout the year, it is in the summer dry season that the great fishing expeditions on the lakes of the mid-Içana occur. The Baniwa know many techniques for fishing including the use of traps and nets, hooks, bow and arrow, machetes and spears and fish poison. Both fishing and agriculture are activities that are synchronized with a variety of environmental indicators and mythical calendars and, in the past, were connected with a series of important rituals.

Probably commercial and extractive activities have contributed the most to change traditional subsistence patterns. From early on in their contact history, the Baniwa have participated in a series of extractive activities such as piaçava, borracha, sorva, castanha, and minerals. Since the distribution of these resources is unequal, seasonal labor migration has become a common pattern. Commercial activities include the production of artwork (baskets, manioc scrapers, feather headdresses) and manioc to sell to merchants, or in urban markets. <object height="203" style="float:right" width="270"> <param name="movie" value="http://www.youtube.com/v/LqgNUO2900o?version=3&hl=pt_BR&rel=0"/> <param name="allowFullScreen" value="true"/> <param name="allowscriptaccess" value="always"/><embed allowfullscreen="true" allowscriptaccess="always" height="203" src="http://www.youtube.com/v/LqgNUO2900o?version=3&hl=pt_BR&rel=0" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="270"/></object>

The Baniwa are excellent artisans. They are the only producers of manioc scrapers made of wood and quartz points which are distributed throughout the region, through interethnic trade or by merchants. Currently, they are the principal producers of urutu baskets and balaios in a great variety of shapes, sizes and types of designs and colors, which are sold in markets throughout Brazil.

To know more about this activity, see the website Arte Baniwa.

Cosmology

In Baniwa cosmology, the universe is formed by multiple layers, associated with various divinities, spirits, and “other people." According to the drawing made by a Hohodene pajé (see figure to the side), the cosmos basically consists of four levels: Wapinakwa ("the place of our bones"), Hekwapi ("this world"), Apakwa Hekwapi ("the other world") e Apakwa Eenu ("the sky of the other world").

Another pajé elaborated an even more complex scheme consisting of 25 layers: 12 below the earth and 12 above. Each one of the layers below the earth is inhabited by “people” with distinctive characteristics (people painted red, people with large mouths, etc.). Above the level of our world are the places of various spirits and divinities related to the pajés: bird-spirits who help the pajé in his search for lost souls; the Lord of Sicknesses, Kuwai, whom the pajé seeks in order to cure more serious ailments; the primordial pajés and Dzulíferi, the Lord of pariká (shaman’s snuff) and tobacco; and finally, the place of the Creator and Transformer Nhiãperikuli, or 'Dio' which is a paradise, the source of all remedies, and the place where the harpy eagle, Kamathawa, Nhiáperikuli’s pet, also lives.

Baniwa cosmogony (that is, the time of the beginning of the world) is remembered in a complex set of numerous myths the main protagonist of which is Nhiãperikuli, beginning with the appearance of the primordial world and ending with his creation of the first ancestors of the Baniwa phratries and Nhiãperikuli’s withdrawal from the world. More than any other figure of the Baniwa pantheon, Nhiãperikuli was responsible for the form and essence of the world, for which reason he may be considered the Supreme Being of Baniwa religion.

The name Nhiãperikuli means "He inside the bone", referring to his origin. Summarizing this story, in the beginning of the world, tribes of savage animals roamed about the world, then miniature, killing and devouring people. One day the chief of the animals took a bone from the finger of a person whom he had devoured and threw it into the middle of the river. An old woman wept for the loss of her kin; so the animal chief ordered her to fetch the bone. There were three shrimp inside the bone; she got it and took it back to the house with her. There they transformed into crickets. She gave them food and they began to sing and grow. Later she took them to her garden and again gave them food. They continued transforming, growing and singing, until they appeared like people: three brothers called the Nhiãperikunai ("They inside the bone"). The old woman warned them not to make any noise, but they began to transform everything and thus they made the world. When they finished, they decided to take vengeance against the animals who had killed their kin. The story then recounts a series of acts of vengeance in which the heroes finally re-establish order in the world. After awhile, however, the chief of the animals – wanting to kill the three brothers – made a new garden and called the brothers to help him burn it. While he sent them to the center of the garden, the chief set fire to the borders. But each of the brothers made a small hole in an ambaúba treetrunk, got inside, and closed off the hole. When the fire (described in the myth as a conflagration which burned the world) approached the center, the ambaúba trunks exploded one after another, and the three brothers flew out, saved from the flames and henceforth immortal. They went down to the river to bathe and, when the chief of the animals approached, they blew magic spells over him.

In this summary, one perceives that the initial situation of the cosmos is one of chaos and catastrophe and, in Baniwa mythology, there are other similarly catastrophic situations, which likewise represent the prelude to the creation of a new order, when the forces of chaos are controlled. In the myth of the beginning of Nhiãperikuli, the bone is the symbolic vehicle that represents the beings who would recreate order in the new world. Catastrophic destruction, however, still remains as a real possibility today, for when the world becomes infested by insupportable evil – witchcraft, sorcery, killings – the conditions are then sufficient for destruction and renewal.

The second great cycle in the history of the cosmos is told in the myths of Kuwai, the son of Nhiãperikuli and the first woman, Amaru. These myths have a central importance in Baniwa culture for they explain at least four major questions on the nature of existence in the world: how the order and ways of life of the ancestors are reproduced for all future generations, the Walimanai; how children are to be instructed about the nature of the world; how sicknesses and misfortune entered the world; and what is the nature of the relation among humans, spirits, and animals, that is the legacy of the primordial world.

The myth tells of the life of Kuwai who is an extraordinary being, whose body is full of holes and consists of all the elements of the world, and whose humming and songs produce all animal species. His birth sets in motion a rapid process of growth in which the miniature and chaotic world of Nhiãperikuli opens up to its real-life size.

Kuwai teaches humanity the first rites of initiation. During the period of seclusion of four boys being initiated, three of them break their restrictions against eating roasted food which causes a catastrophe to occur. Kuwai transforms into a monster and devours the three initiates who had broken the fast by eating roasted uacú nuts. At the conclusion of the ritual, however, Nhiãperikuli kills Kuwai, pushing him into an enormous fire, which some narrators describe as an “inferno” that burnt the earth, reducing the world again to its miniature size. From the ashes of Kuwai’s fire, there emerged an enormous paxiúba tree and other plant materials with which Nhiãperikuli made the first sacred flutes and trumpets that would be played in rites of initiation and sacred cerimonies for all future generations of Walimanai. Amaru and the women, however, stole these flutes from Nhiãperikuli, which set off a long chase in which the world opened up a second time, as the women, fleeing from Nhiãperikuli, play the flutes throughout the entire world. Nhiãperikuli and the men, disguised as animals, finally catch up to the women, make war against them, and regain the instruments. With them, Nhiãperikuli later looks for the first ancestors of humanity who emerged from the holes of the sacred rapids of Hipana on the Aiari River.

The myth of Kuwai marks a transition between the primordial world of Nhiãperikuli and a more recent human past, which is brought directly into the experience of living people in the rituals. For that reason, the pajés say that Kuwai is as much a part of the present world as of the ancient world, and that he lives “in the center of the world". For the pajés, he is the “Lord of Sicknesses" and it is he whom they seek in their cures, for his body consists of all sicknesses that exist in the world – including poison used in witchcraft and which still is the most frequently cited ‘cause’ of death of people today – the material forms of which he left in this world in the great conflagration that marked his “death” and withdrawal from the world. The pajés say that Kuwai’s body is covered with fur like the black sloth called wamu. Kuwai ensnares the souls of the sick, grasping them in his arms (as the sloth does), and suffocating them until the pajés bargain with him to regain the souls and return them to their owners.

A fundamental consequence of Baniwa cosmogony is that the world of humans is inherently flawed by evil, wicked people who cause harm and put sickness on others, and by the misfortune of death. The pajés call this world maatchíkwe, place of evil; kaiwikwe, place of pain; ekúkwe, place of rot, due to there being so many dead rotting beneath the earth. In contrast, the other worlds of the cosmos – principally that of Nhiãperikuli – are considered beautiful places, without sickness, without evil, eternally young. Like a sick person, this world of humans needs to be constantly freed of evil, of witchcraft and sorcery that bring on suffering and death. Thus the role of the pajés is as "guardians of the Cosmos", and the chanters in rituals of initiation perform lengthy chants in order to make the world safe for the new generations.

Religious life

Baniwa religious life was traditionally based on the great mythological and ritual cycles related to the first ancestors and symbolized by the sacred flutes and trumpets, on the central importance of shamanism (pajés and chanters, or chant-owners) and on a rich variety of dance rituals, called pudali, associated with the seasonal cycles and the maturation of forest fruits.

The initiation rituals are celebrated during the time of the first rains and the maturation of certain forest fruits, when there is a group of boys between ten and thirteen years of age who are considered ready to be instructed about the nature of the world. It is absolutely prohibited for the women and uninitiated to see the sacred flutes and trumpets, under pain of death by poison.

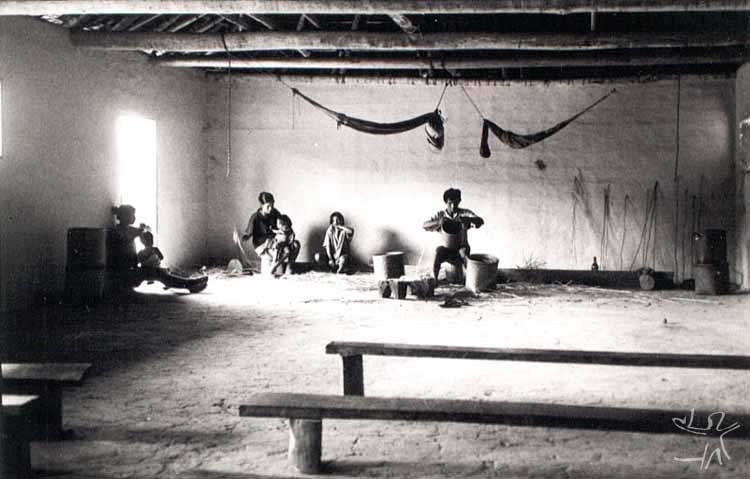

The ritual is celebrated in three phases: in the first, called wakapethakan, or "we whip", the “owner of the ritual” (who is responsible for the organization of all the preparations and is the owner of the house where the ritual will take place) sends the men to the forest to gather fruits and orders the women to make manioc beer, caxiri. When all is ready, on the appointed day, the men go down to the port where the sacred flutes and trumpets are hidden, paint themselves black with carbon, and wait for the calling.

An elder, the chant-owner of the ritual, stays together with the initiates who are blindfolded, at the door of the ritual house and, with a ritual staff in hand, he calls out to the ancestors of the sib, represented by the flutes and trumpets, three times, and each time, the men respond by blowing the flutes. On the third calling, the men march in procession up from the port playing the flutes and trumpets in unison, parading in front of the house until finally they stop and place the instruments on the ground. At that moment, the elder removes the blindfolds and shows the boys the instruments, explaining their significance, the prohibitions against speaking about them, and how they are to stay in seclusion for one month (these days, two weeks), until they are ready to come out of the ritual house. From that moment on, the boys stay in seclusion, fasting on forest fruits, learning the myths, and – most importantly – learning how to make all kinds of basketry.

In the final phase, the owner of the ritual invites the elder chanter and two companions to perform the most important part of the initiation ritual – chanting over pepper and salt, called Kalidzamai. For one whole night, the elders chant, while the men play the instruments and drink caxiri, recreating – in their thought – the voyages of Amaru throughout the world with the instruments while Nhiãperikuli and the men pursued them. With these chants, the elders blow protective smoke over the pepper and salt, which will later be served to the initiates on a piece of manioc bread. Having finished the chants, as the sun is rising, the elders present the sacralized pepper to the owner of the ritual and he calls the initiates to stand in front of him in order to hear their counsel on how to live in the world after they have left the initiation house. After giving the counsel, the elder takes his ritual whip and strikes the boys three times on their chests.

Having completed the phase of seclusion, the final phase of coming out of the house, wamathuitakaruina, begins, that is, the integration of the initiates into adult life. The initiates are painted all in red (a color symbolizing happiness) by their mothers, and ornamented with feather crowns and heron down. Carrying the manioc sifters that they have made during their seclusion, they form a line and, at a signal, they come out of the house as the men sing. They come out and go back in three times and, on the third time, each of them presents his manioc sifter to a girl, chosen to be the initiate’s partner, called a kamarara, "like a wife". At that time, the ritual ends, in the midst of much festival and happiness, for a new generation of adults has been produced.

The initiation rituals for girls happen soon after their first menstruation. The organization of the ritual is like that for the boys; girls, however, generally are initiated individually since menstrual cycles begin at different times. First, their hair is cut short, “like the boys” and they are not shown the sacred instruments. During the period of seclusion, the girl learns how to make manioc scrapers (which involves the extremely detailed task of fixing pieces of quartz in geometric patterns onto a board cut and prepared by the men), various kinds of ceramics (painted plates especially), the woven materials for making manioc bread; besides everything about how to take care of gardens, cooking, etc. After the pepper is prepared, the girl – ornamented and painted like the boys – is instructed to stand inside a manioc bread basket, while another basket, ornamented with heron feathers, is placed upside down over her head, symbolizing her status as the maker of manioc bread, the daily sustenance of the community. She receives the sacralized pepper, and then receives from her aunt or grandmother and the elder chanter the specific instructions for girls on how to live in the world. Finally, she, like the boys, is whipped three times on the chest.

Another important ritual celebrated by the Indians of the region is the pudali (or dabukuri in língua geral), principally during the times of the ripening of forest fruits, but also on other occasions such as the piracema, when fish migrate upriver in great numbers to spawn. These are occasions when kin and affines get together to drink caxiri (either manioc beer or fruits such as pupunha) and dance. On these happy occasions, whatever conflicts that exist among affines, for example, can be settled.

There is a great variety of types of pudali: Mawakuápan, a dance with whistles called mawaku, made of pieces of sugarcane; Wethiriápan, celebrated when the ingá fruit ripens; Heemápana, when the participants drink the psychoactive caapi (Banisteriopsis sp) and dance with rattles; Aaliapan, dance of the jaburú; Kapetheápan, dance with whips, which is the festival of Kuwai, also called Kuwaiápan celebrated at the beginning of the rains; Wanaapan, dance of the ambaúba treetrunks; and Kuliriápan, the dance of the surubi fish – perhaps the most famous of the Baniwa pudali, when surubi flutes are made in great quantities. The flutes are made of paxiúba, with basketwork in the form of the surubí fish, painted brown and white, and ornamented with heron feathers. Even today, several communities of the upper Aiari make this kind of flute and celebrate this dance. It is the flute and dance which most distinguish the Baniwa from other peoples of the region.

Besides these dances, the Baniwa – at least those of the upper Aiari until the beginning of the 20th Century – had masked dances, called hiwidaropathi, representing various spirits and animals. Koch-Grünberg photographed these dances among the communities of the upper Aiari in 1903, as well as various instruments (flutes) and ornaments (acangataras, bracelets, ankle rattles), which are no longer made.

In relation to shamanism, there are two main categories of shamans: the chant-owners (malikai-iminali) and the pajés (maliiri). The pajés can be chant-owners and vice versa, but there are differences in the training, cures, and knowledge that each dominates. The pajés "suck out” (extract by suction pathogenic objects from their patients), while the chant-owners “blow”, or, as they say, "pray" (sing or recite formulas with tobacco on herbs and medicinal plants to be consumed by the patients). Only the pajés use rattles with their songs and dances and the sacred hallucinogenic powder pariká in their cures, which puts them into a state of transe. For the chant-owners, tobacco and a gourd of water are the principal instruments. Both the pajés and the chant-owners have extensive knowldge of medicinal plants used in cures.

A great part of the power of the pajés lies in their extensive knowledge and understanding of mythology and cosmology, as well as the detailed and systematic understanding of the multiple sources of sicknesses and their cures. Through their role as mediator between the sick and the spirits and deities of the Baniwa pantheon, the pajés cure, counsel, and guide the people, thus performing one of the most vital servives for the continued health and well-being of the community. It is believed that true pajés can transform into various powerful animals, notably the jaguar, and into the divinities themselves. Normally, the pajés perform their cures in groups of two or three, with a leader guiding the songs and ritual actions.

The chant-owners, in turn, mainly use chants, accompanied by tobacco-blowing over medicinal plants. They are mainly elders who chant or recite these formulas in order to perform various tasks: protection against sicknesses, cure and alleviating pain, or even calling animals for hunting and fishing, or to make gardens grow, among other activities. The more knowledgeable elders also know how to perform the special chants called Kalidzamai, sung during the rites of passage (birth, initiation and death). These chants represent a highly specialized and esoteric knowledge of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the cosmos and classes of being. It is the most sacred and powerful of all activities known by the chant-owners.

In the 1950s and 60s, serious religious conflicts erupted in Baniwa communities as the result of evangelization by Protestant and Catholic missionaries, which introduced a previously inexistant tension between religious specialists. Protestant communities, especially, lost all of their pajés, along with the flute cults and the Kalidzamai chanters. Only the chant-owners of lesser importance continued with their knowledge and practice without persecution. The intolerance of the protestant missionaries provoked a spiritual crisis among the chant-owners, many of whom claimed that a “sickness” made them forget their art. Several more radical pastors, moreover, waged campaigns against the pajés of the Aiari river, the only place in Baniwa territory where shamanism is still practiced. Today, the institution is in decline, with only a half-dozen pajés in all Baniwa territory in Brazil.

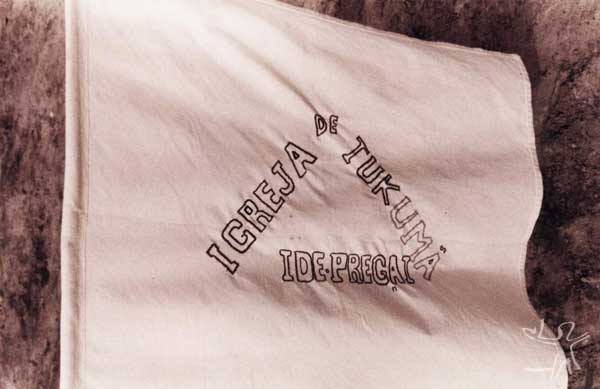

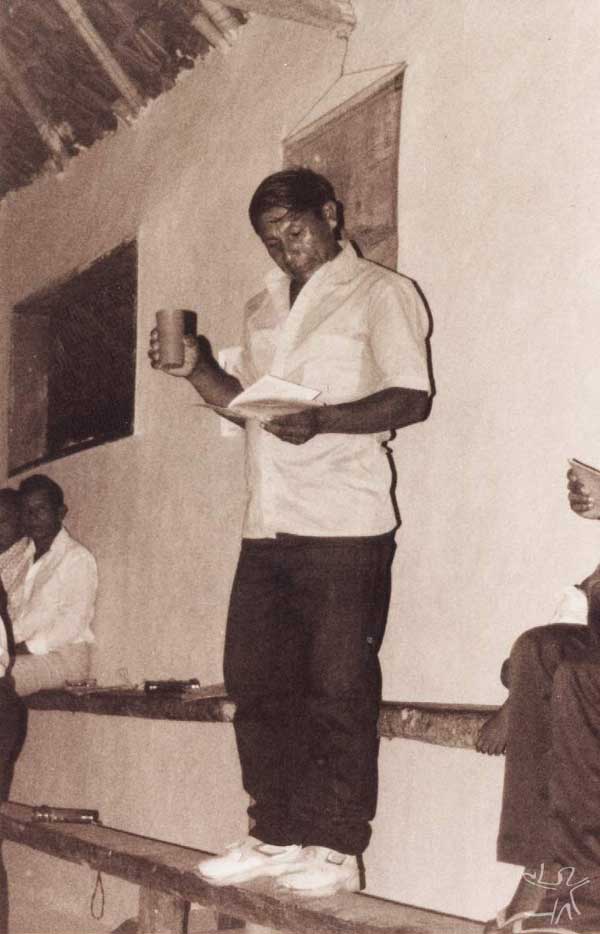

With their conversion to evangelism, all pudali were prohibited by the missionaries and their followers. Thus, there is an entire generation today which has never heard the music of the pudali. The great change provoked by the loss of these rituals is evidenced by the innumerable conflicts between “believers” and “traditionals” over the way in which the sacred instruments and traditions were “thrown away.” Tobacco and caxiri, also prohibited, were two things that, according to the Baniwa, brought happiness to their souls. With their prohibition, naturally, internal conflicts also increased. Instead of these, the believers introduced readings of the Evangelists, the monthly cerimonies of Holy Supper and the Conferences (every two or three months), which, once consolidated, substituted the pudali. Thus, today, among believer communities, such cerimonies provide occasions of happiness, when, - besides the Biblical teachings – there is an abundance of food and games for all.

Note on the sources

Very little was known of Baniwa society and culture until the beginning of the 20th Century, when the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg spent several months on the Içana and Aiari and left the first extensive ethnographic records on them. Before then, several scientific travellers, such as Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira in the 1780s, Johann Natterer in the 1820s, and Alfred Russell Wallace in 1852-3, left a few notes on their contacts with the Baniwa, as did various missionaries and military. There is extensive documentation on the messianic movements of the mid-19th Century to be found in the Arquivo Histórico Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, and in the Arquivo Público and the Instituto Histórico e Geográphico Brasileiro, both in Manaus.

These documents were left by government officials, military officials, and missionaries who were in direct contact with the indigenous communities engaged in the movements; they are extremely useful for reconstructing this history and, to a certain extent, contain ethnographic information. On the other hand, their value is limited by the interests of their authors in suppressing the movements and controlling the border region from presumed foreign invasions. Besides these, various official commissions, such as the First Commission for the Demarcation of the Borders (archives in Belém do Pará), have left valuable information concerning population. The informative and sensitive ethnography written by the mayor of the Venezuelan town of Maroa, Martín Matos Arvelo (1912) refers to the Baniva people who, as mentioned in the introduction, are distinct from the Baniwa and Kuripako.

Thus it was the pioneering work of Koch-Grünberg that initiated Baniwa ethnography. Since then, in intervals of nearly every 25 years, ethnographers have visited or worked on the Içana and its tributaries, producing the records essential for reconstructing the recent history of the Baniwa: Curt Nimuendajú in 1927, Eduardo Galvão in 1954, Adélia de Oliveira in 1971, Berta Ribeiro in 1977. Since 1976, Robin Wright has dedicated his anthropological work to the history and religious ethnography of the Baniwa, mainly of the Aiari River, producing numerous articles and a book on their religion, history, mythology, warfare, shamanism, prophetic movements, and conversion to evangelical protestantism.

The production of the anthropologist Jonathan Hill on the Wakuenai of Venezuela includes articles on social exchange, social organization and ecology, ritual and cerimonial life, and a book on specialist chanters. On the Colombian side, Nicolas Journet has produced an ethnography of the Kuripako, focussing on social organization, kinship, warfare, political and economic organization, and ritual exchange.

Finally, there is a book of myths of the Baniwa of the Aiari River, A Sabedoria dos Nossos Antepassados (The Wisdom of our Ancestors), produced by the Association of Indigenous Communities of the Aiari River, with the collaboration of the anthropologist Robin Wright. The book is the third volume of the series Indigenous Narrators of the Rio Negro, published by the Federação das Organizações Indígenas do Rio Negro (FOIRN). The volume contains nearly all the myths recorded by the anthropologist during his fieldwork on the Aiari in 1976-7 among the Hohodene and Walipere dakenai. The anthropologist organized a first version of the collection which was then discussed in detail with indigenous narrators, in order to clarify obscure points. A second version was produced which was then revised by several people, both anthropologists and indigenous narrators, until all agreed on the final version.

Sources of information

Baniwa

- BEZERRA, Elizabeth Ferreira et al, orgs. Vamos escrever nossa língua! : Método experimental de alfabetização para falantes de Baniwa. Manaus : Univ. do Amazonas, 1992. 67 p. (Caderno de Leitura Baniwa, 1)

- CASTELLANOS, Juan M., ed. Fepaite, nuestro territorio : Atlas Curripaco. Bogotá : Papawiya, Ñewiam, 1992. 60 p.

- CHIAPPINO, Jean; ALES, Catherine, eds. Del microscopio a la maraca. Caracas : Ex Libris, 1997. 402 p.

- GARNELO, Luiza; WRIGHT, Robin. Doença, cura e serviços de saúde : representações, praticas e demandas Baniwa. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 17, n. 2, p. 273-84, mar./abr. 2001.

- HILL, Jonathan; MORAN, Emílio F. Adaptive strategies of Wakuénai peoples to the oligotrophic rain forest of the Rio Negro Basin. In: HAMES, Raymond B.; VICKERS, William T., eds. Adaptive responsees of native amazonians. New York : Academic Press, 1983. p. 113-38.

- JOURNET, Nicolas. Los Curripaco del rio Isana : economia y sociedad. Rev. Colombiana de Antropologia, Bogotá : Instituto Colombiano de Antropologia, n.23, p.127-82, 1981.

- --------. Hommes et femmes dans la terminologie de parenté curripaco. Amerindia, Paris : A.E.A., n. 18, p. 40-74, 1993.

- --------. Les jardins de paix : Etude des structures sociales chez les Curripaco du Haut Rio Negro. Paris : École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1988. 473p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. La paix des jardins : structures sociales des indiens curripaco du haut Rio Negro. Paris : Institut d'Ethnologie, 1995.

- KNOBLOCH, Francis A. The Baniwa indians and their reaction against integration. The Manking Quarterly, Edinburgh : R. Gayre of Gayre, v.15, n.2, p.83-91, out./dez. 1974.

- MEIRA, Márcio. Laudo antropológico Área Indígena Baixo Rio Negro. Belém : MPEG, 1991. 183 p.

- MOHRENWEISER, Harvey et al. Eletrophoretic variants in threee amerindian tribes : the Baniwa, Kanamari, and Central Pano of Western Brazil. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, New York : Alan R. Liss, n.50, p.237-46, 1979.

- MULLER, S. Beyond civilization : a collection of letters written to describe jungle journeys while pioneering among a hitherto unreached indian tribe in the jungles of South America. Wisconsin : Brown Gold Publications, 1952. 128 p.

- NIMUENDAJU, Curt. Reconhecimento dos rios Içana, Ayari e Uaupés : março a julho de 1927 - Apontamentos Lingüísticos. Parte II. Journal Sociétè des Américanistes, Paris : Sociétè des Américanistes, n.44, p.149-97, 1955.

- OLIVEIRA, Adelia Engracia de. Depoimentos Baniwa sobre as relações entre índios e “civilizados” no Rio Negro. Boletim do MPEG: Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, n.72, 31 p., jan. 1979.

- --------. “Co yvy oguereco ijara” : Esta terra tem dono. Ciência Hoje, Rio de Janeiro : SBPC, v.2, n.10, p. 58-65, jan./fev. 1984.

- --------. A terminologia de parentesco Baniwa - 1971. Boletim do MPEG: Série Antropologia, n.56, 34 p., jan. 1975.

- OLIVEIRA, Ana Gita de. O mundo transformado : um estudo da "cultura de fronteira" no Alto Rio Negro. Brasília : UnB-ICH, 1992. 286 p. (Tese de Doutorado) Esta tese foi publicada no final de 1995 pelo MPEG de Belém dentro da Coleção Eduardo Galvão.

- ORTIZ, Francisco, ed. Waaku Idana : cartilha para leer y escribir en Curripaco - Aja. Bogotá : Fundación Etnollano, 1993. 64 p.

- PEREIRA, Maria Luiza Garnelo. Poder, hierarquia e reciprocidade : os caminhos da política e da saúde no Alto Rio Negro. 2 v. Campinas : Unicamp, 2002. 476 p. (Tese de Doutorado).

- RIBEIRO, Berta. A civilização da palha : a arte do trançado dos índios do Brasil. São Paulo : USP, 1980. 590 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- RICARDO, Carlos Alberto; MARTINELLI, Pedro. Arte Baniwa : cestaria de arumã. 2a. ed. revisada. São Paulo : ISA ; São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Foirn, 2000. 64 p.

- ROJAS SABANA, Filintro Antônio. Ciencias naturales en la mitologia Curripaco. Bogotá : Fundación Etnollano, 1997. 266 p. --------. Relatos astronomicos Curripaco. Bogotá : Fundación Etnollano, 1992. 48 p.

- ROMERO, Manuel. La territorialidad para los Curripaco. Informes Antropológicos, Bogotá : Inst. Colombiano de Antropología, n. 6, p. 5-32, 1993.

- SAAKE, Guilherme. O mito do Jurupari entre os Baníwa do rio Içana. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 277-85. --------. Uma narração mítica dos Baníwa. In: SCHADEN, Egon. Leituras de etnologia brasileira. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976. p. 286-91.

- SALZANO, Francisco M. et al. Gene flow across tribal barriers and its effect among the Amazonia Icana River indians. American Journal. of Physical Anthropology,New York : s.ed., p.3-14, 1986.

- SANTOS, Antônio Maria de Souza. Etnia e urbanização no Alto Rio Negro : São Gabriel da Cachoeira-AM. Porto Alegre : UFRS, 1983. 154 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SILVA, Algenir Ferraz Suano da, ed. Manual de doenças tradicionais Baniwa. Manaus : EDUA, 2001. 39 p.

- SOUZA, Boanerges Lopes de. Do Rio Negro ao Orenoco : a terra, o homem. Rio de Janeiro : CNPI, 1959. 260 p.

- TAYLOR, Gerald. Introdução à língua baniwa do Içana. Campinas : Editora da Unicamp, 1991. 136 p. --------. Proposta ortográfica para o Baniwa do Içana. Chantiers-Amerindia, Paris : A.E.A., n.2, 20 p., jan. 1989.

- TELES, Iara Maria. Atualização fonética da proeminência acentual em baniwa-hohodene : parâmetros físicos. Florianópolis : UFSC, 1995. (Tese de Doutorado)

- WEIGEL, Valeria Augusta C. de M. Escolas de branco em malokas de índio : formas e significados da educação dos Baniwa do rio Içana. São Paulo : PUC-SP, 1998. 294 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- WRIGHT, Robin M. Os Baniwa no Brasil. In: KASBURG, Carola; GRAMKOW, Márcia Maria, orgs. Demarcando terras indígenas : experiências e desafios de um projeto de parceria. Brasília : Funai/PPTAL/GTZ, 1999. p. 281-95.

- --------. For those unborn : cosmos, self and history in Baniwa religion. Austin : Univer. of Texas Press, 1998. 301 p.

- --------. Guardians of the cosmos, Baniwa shamans and prophets : I. History of Religions, Chicago : Univ. of Chicago, v. 32, n. 1, p. 32-58, ago. 1992.

- --------. Guardians of the cosmos, Baniwa shamans and prophets : II. History of Religions, Chicago : Univ. of Chicago, v. 32, n. 2, p. 126-45, nov. 1992.

- --------. History and religion of the Baniwa peoples of the Upper rio Negro valley. Stanford : Stanford University, 1981. 630 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. Ialanawinai : o branco na história e mito Baniwa. In: ALBERT, Bruce; RAMOS, Alcida Rita, orgs. Pacificando o branco : cosmologias do contato no Norte-Amazônico. São Paulo : Unesp ; Imprensa Oficial, 2002. p.431-68.

- --------. Pursuing the spirits : semantic construction in hohodene kalidzamai chants for initiation. Amerindia, Paris : A.E.A., n. 18, p. 1-40, 1993.

- --------. O tempo de Sophie : história e cosmologia da conversão Baniwa. In: WRIGHT, Robin, org. Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 155-216.

- --------. Umawali : hohodene myths of the anaconda, father of the fish. Bulletin de la Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, Genebra : Soc. Suisse des Américanistes, n. 57/58, p. 37-48, 1995.

- --------, org. Waferinaipe Ianheke, a sabedoria dos nossos antepassados : histórias dos Hohodene e dos Walipere-Dakenai do rio Aiari. Rio Aiari : Acira ; São Gabriel da Cachoeira : Foirn, 1999. 192 p. (Narradores Indígenas do Rio Negro, 3)

- Arte Baniwa - Rio Negro, Amazonas. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 6 min., 2000. Prod.: Instituto Socioambiental

VIDEOS