Cinta larga

- Self-denomination

- Matetamãe

- Where they are How many

- MT, RO 1954 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Mondé

The name “Broad Belt" [Cinta Larga] or "Broad Big Belt” [ Cinturão Largo] had been used to refer to several groups who inhabit the region near the border between Rondônia and Mato Grosso, since all of these groups used some kind of belt and built large and long houses.

The main activity of this Tupi group is hunting, and festivals, when the game is consumed after a complex ritual, which symbolically equates hunting and warfare, thus revealing significant aspects of Cinta Larga society and guaranteeing the equilibrium of the group. This equilibrium in the last few years has been deeply upset by the presence of goldpanners on their lands.

Identification and location

The name Cinta Larga is a generic designation invented by the regional population and adopted by the National Indian Foundation (Funai), and results from the fact that the group uses wide belts around their waists which are made from inner treebark. According to available information, it is not possible to discover from the Cinta Larga something like a self-designation, a general term for the whole group – except for the nickname “Broad Belt", which they have adopted as a result of their living together with members of Brazilian society. One cannot accept hasty translations, as one sometimes sees, for generic expressions such as “we” or “our people”, which in the Cinta Larga language is pãzérey (pã-, personal pronoun, 1ª person. plural; zét, person; -ey, plural). The Cinta Larga are emphatic in saying: "We don’t give a name, the ones who give names are the others". In other words, an Other seems to be necessary in order to give a name to this We-ness, someone who, being from the outside, defines and names his opposite.

Located in the southwest of the Brazilian Amazon, the traditional territory of this group which covers part of the states of Rondônia and Mato Grosso, extends from the region around the left bank of the Juruena River, near the Vermelho River, up to the headwaters of the Juina Mirim River; from the headwaters of the Aripuanã River to the waterfall of Dardanelos; on the headwaters of the Tenente Marques and the Capitão Cardoso rivers and the areas surrounding the Eugênia, Amarelo, Amarelinho, Guariba, Branco do Aripuanã and Roosevelt rivers. They inhabit the Roosevelt, Serra Morena, Parque Aripuanã and Aripuanã indigenous lands, all of which are ratified, in a total area of 2.7 million hectares.

The population is distributed into three large groupings. Way to the south, in the areas around the Tenente Marques and Eugênia rivers, are the villages of Paábiey (“those from above”), or Obiey (“from the headwaters”). Near the juncture of the Capitão Cardoso and Roosevelt rivers live the Pabirey (“those of the middle”). And, slightly more to the north, on the Vermelho, Amarelo and Branco rivers, there are the Paepiey (“those from below”). The Cinta Larga think of their spatial distribution in terms of an axis that follows the directions in which the waters of the Aripuanã and Roosevelt rivers flow, which, in this part, run nearly parallel from south to north. Thus, they use categories high/middle/low, that refer to a space which is defined by a slope, distinguishing the groupings in relation to each other, in accordance with the geographical position that each occupies.

To understand the present distribution of the Cinta Larga population, it is necessary to consider that, besides the spatial and ecological codes that provide terms for identifying the groupings, the relations between the group and the national society, in particular the intervention of the Brazilian state, have consolidated a quite specific referential system. It was in the midst of a complex interplay of pressures, omissions and mainly concessions to economic and political interests that the Funai came to define four contiguous indigenous lands, within the territory inhabited by the Cinta Larga. They are: the Aripuanã Park, the Roosevelt area, the Serra Morena area and the Aripuanã area. In continuation with these lands are the lands of the Suruí, Zoró and Arara of Beiradão; besides these lands, a narrow corridor separates the Aripuanã Park from the lands of the Salumã (Enawenê-Nawê) and Nambikwara of Campo.

Language and population

The Cinta Larga language belongs to the Tupi Monde family, Tupi linguistic trunk, as do the languages of the neighboring Gavião, Suruí Paiter and Zoró.

In 1969 the Cinta Larga populations was estimated to be around 2,500 people. In 1981 their population was not more than 500 individuals, which was an optimistic estimate. From that time, their population resumed its growth, reaching around 1,302 individuals in 2001 and, in 2003, it is estimated to be around 1,300 individuals.

History of contact

Only in the 20th Century did there emerge precise information about the Indians today called the Cinta-Larga. Two centuries ago, however, information was left by the explorer/ bandeirante Antônio Pires de Campos in the year 1727, who crossed the plateau of the Parecis. Having probably reached the Juruena River in his journey, western border of what he called the “Kingdom of the Parecis”, he came across the “Cavihis Nation” which, from their location and from the ethnographic data that Pires de Campos left about them (1862), could be related to the present-day Cinta-Larga.

The earliest source which makes reference with some certainty to the Cinta Larga is the encounter which took place with the reconnaissance team of the Rondon Commission that explored the Ananaz River in May 1915 – thus crossing through the area of the present-day Aripuanã Park. In the beginning of the journey, the expedition caught sight of several Nambikwara groups, with whom the Commission was already on friendly terms, but later, downriver, near the Perdidos stream, their camp was attacked by Indians from an “unknown nation”, who killed the head of the expedition, lieutenant Marques de Souza, and the canoeman Tertuliano, while the other members of the expeditions managed to escape (A. B. de Magalhães 1941: 455). When the survivors got to Manaus, the Telegraphs Lines commission, conducted an inquiry, concluding that the attacking Indians were “Macaws”- an ambiguous designation which is certainly due to the use of various macaw feathers on their headdresses and armlets, as is the custom of the Cinta Larga and other Tupi-Mondé peoples.

During the 20th Century, various incidents occurred which marked the history of the Cinta Larga: in 1928 a group of rubber-gatherers led by Julio Torres, following orders by the Peruvian Dom Alejandro Lopes, the rubber boss who dominated the Aripuanã River, massacred a village of Indians who were then called “Iamé”- yamên is a typical form of greeting among the Cinta Larga. The case was denounced to the Inspector of the SPI, Bento Martins de Lemos (SPI- Amazonas and Acre Inspectorate 1929: 180-183), who opened a inquiry, but which produced little results.

The Cinta Larga who had their villages in the region of the Rio Branco and Guariba, to the north of the territory, the present Aripuanã indigenous land, had been at war with the rubber-gatherers since the 1950s, and it was from the time of these conflicts that they began to acquire their first metal tools. If the tools became, since then, the principal reason for war, they would also be, according to the discourse of the Cinta Larga themselves, what would lead them to seek to establish relations of reciprocity with the Zarey, the non-Indians.

In the same decade of the 1950s, there are the first records of attacks by the Cinta Larga on the trading posts of the rubber-gatherers, wagon trains of goldpanners and settlements that had grown up in the vicinity of the telegraph stations, particularly Vilhena, José Bonifácio (formerly Três Buritis) and Pimenta Bueno. Several Cinta Larga groups, migrating to the south of the territory, had occupied the headwaters of the Roosevelt and Tenente Marques rivers, dislocating the surviving Nambikwara.

The invasions of the Cinta Larga territory continued during the 1950s by mining and rubber companies, and the situation worsened even more after the inauguration of the Cuiabá-Porto Velho (BR-364) highway, in 1960. Hostile to the invaders, the Cinta Larga represented an impediment to the expansion of these enterprises, particularly along the Juruena and Aripuanã tributaries. As a result, the operations to “clean the area” of the Cinta Larga grew to alarming proportions, organized by the firma Arruda and Junqueira company and others, which exploited rubber and prospected for gold and diamonds in the region.

Among the numerous assaults on the Cinta Larga villages – there are records of expeditions which took place in 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1962 -, one of these crimes was widely publicized and had great impact, including in the international press, the so-called “Massacre at Parallel 11”, which resulted in denunciations of genocidal practices against Indians in Brazil, for one of the participants, Atayde Pereira dos Santos, not having received the payment that he was promised, showed up at the headquarters of the SPI Inspectorate in Cuiabá to denounce the case and indicate the ones responsible for the massacre (A.P.dos Santos 1963).

Even at the end of the 1960s, the Cinta Larga villages, were generally located near small streams, according to the reports of backwoodsmen and missionaries who flew over the territory of the Roosevelt and Aripuanã rivers and their tributaries. A few years later, in 1976, a map prepared by the photographer Jesco Von Puttkamer indicated precisely 16 Cinta Larga villages and two Funai posts. In the years following the depopulation and the attraction policy of the Funai posts, concentrating the indigenous population, the total number of villages was substantially reduced. In the Aripuanã area, where the Funai only established itself in 1984, when the Ouro Preto prospecting area was de-activated, eight villages were set up there at the same time, being established at distances which varied from ten to a hundred kilometers apart, with the total population of the area being only 90 people. In 1987, however, half of this population was already residing on the Rio Preto post, the name that the Funai gave to the place of the old prospecting site, while the rest was divided among four remaining villages.

Pacification: another war

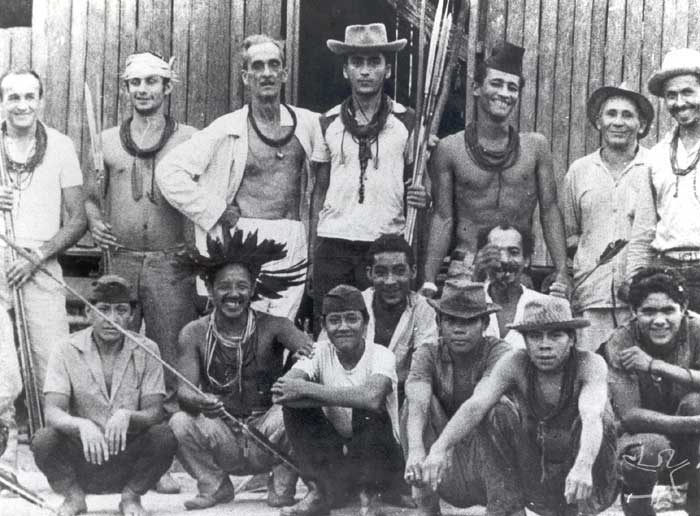

A visit from the Cinta Larga surprised the dwellers of the town of Vilhena (Ro) in February, 1965: unarmed, around 60 “Indians” set up camp near the old telegraph station, exchanged presents and watched a soccer match.

According to Father Ângelo Spadari (1984: pers. Info.), who was at that time parish priest in the village, a young man came to the house of the retired telegraphman Marciano Zonoecê, a Paresi Indian, and, trembling, pressed his belly in a sign of hunger. The telegraphman brought manioc cereal and sugar, and soon the other Cinta Larga approached, in small groups – young men, an elderly couple and a young girl. The FAB [Brazilian Air Force] detachment, located six kilometers away, was advised of the Indians’arrrival, and sent a truck-cart with supplies, trinkets, and various articles. Quite at ease, the Cinta Larga stayed at the Post until nearly mid-night, little by little going off to sleep.

In June of the same year, the commander of the FAB detachment, Sergeant Pereira, made note of vestiges left by the Cinta Larga on the headwaters of the Iquê, a few kilometers from Vilhena, whom he presumed went out on hunting expeditions (Archives of the SPI: microfilm 236, p.505). In May, 1966, however, another visit to the same telegraph station degenerated into conflict. In mid-afternoon, around 20 Cinta Larga, among them only one woman, came apparently on a “peaceful mission”, walking on the clearing of the telegraph line and were amicably received by the head of the station Marciano, the Bolivian Victor Garcia and by Anízio Ribeiro da Silva, nicknamed “Parazão”, worker of the 5th Engineering and Construction Battalion (BEC). But an accidental gunshot, from a hunter who was coming in the BEC truck to get to know the visitors, provoked a sudden response from the Cinta Larga, who mortally wounded Parazão and his dog, and wounded the Bolivian Victorio and Marciano’s daughter. The girl reacted with shotgun fire and, at the arrival of the truck, the Cinta Larga fled.

At that time, the prospectors numbered in the hundreds, and were combing the region for diamonds, gold and cassiterite, and the conflicts broke out in a dramatic way. At the very end of the 60s, the hostilities got worse with cases of Cinta Larga shooting various regional people on more than one occasion and, at other moments, being the target of gunshots by rubber-gatherers and other inhabitants of the region.

Thinking that they were dealing with the same ethnic group that was already frequenting the Sete de Setembro Post, the Funai quickly took measures to remove the prospectors and establish the Roosevelt sub-post, taking advantage of the short landing-strip and the barracks built by the prospectors. And in this way they continued contacts with the Cinta Larga. In fact, it was a virulent flu epidemic that decimated the population of several villages. The survivors planned to take revenge, and attacked the camp where the Funai had recently become established. For the Cinta Larga this would be the most plausible explanation for such a lethal disease, which until then was unknown. Accusations of poisoning are frequent when there are deaths or sicknesses, since that kind of assault is quite common.

Throughout their history of contact, the relations between the Cinta Larga and the Brazilian national society have been very distinct: all of the friendly contacts have been established through a clear initiative on the part of the indigenous peoples. Thus, we could say that it was the the Cinta Larga who pacified the “whites”; an unprecedented accomplishment, in January 1974, the “pacification”, ostensibly derived from the Cinta Larga themselves. When they talk about their visit to the city, in effect, the Cinta Larga who participated in the adventure explain that they wanted to obtain tools - dabékara weribáte: they had no more axes and machetes. And they recall the dramatic moments of the undertaking, which took place through a series of approaches. Observing the route of the planes, the presence of which became more frequent in Aripuanã from the beginning of the “Aripuanã Project” (the pioneering Humboldt nucleus, of the Federal University of Mato Grosso), they came to Paíkini. And today, Paíkini designates this happening for them, with a word that they, the Aripuanã dwellers, thought meant “friend”. The Cinta Larga indeed wanted to meet up with the Whites, and receive the desired metal tools – thus changing radically the nature of the relationship that they had maintained with the Zarey.

Social organization

The Cinta Larga groups are Mân (with various subdivisions), Kakín (with subdivisions) and Kabân (no subdivisions). Probably, before, there was greater clarity in the demographic distribution of these divisions: the Kabân to the north, in the region of the Branco and Vermelho rivers, the Mâmderey in the middle, and the Mâmjiwáp on the headwaters of the Tenente Marques and Eugênia rivers. After the establishment of the Funai posts, a series of changes were made in the spatial occupation of these groups.

The family is the most important unit of Cinta Larga social organization: it is practically self-sufficient and is free to move from one village to another. A man, his wives and children take care of the complementary activities which are necessary for life – each village has one or two large houses – in the Aripuanã area, there were three to five families: the owner of the house, his wives, married or single sons, single daughters and sons’ wives, perhaps their brothers and families, sometimes their married daughters and daughters’ husbands.

In effect, the village is constituted and organized around a prestigious man - zápiway, literally, the ‘owner of the house. The leadership that this man exercises results, to begin with, from his predisposition to take initiatives, such as in building a new house, clearing a garden, organizing festivals, and also, arranging marriages.

Thus founded by a man who wishes to have his own záp – the term designates both the place and the building -, the village remains as long as the necessary ecological and political conditions continue: abundance of game, strips of fertile land in the area, good relations with neighboring villages. If these conditions do not exist any longer, moving from the place occurs in intervals of five years or less.

The relation of descent between father and son, thus, seems to offer the basis for cohesion of a Cinta Larga village – which differentiates it, as everything indicates, from the Zoró model, where the uxorilocal residential choice joins, from the beginning, wife’s father and daughter’s husband and distinguishes the male children. In the case of the Cinta Larga, the choice is evidently patrilocal, although this is conditioned by injunctions of a political nature. The male children, with their wives and children are accustomed to living together sometimes until the death of their father when they then separate to establish their own villages. These villages, however, are relatively close geographically, on the average 10 to 15 kilometers between them, and their members are used to visiting each other frequently, just to visit or for other exchanges.

Traditionally, - above all before contacts with the Funai, the Cinta Larga villages consisted of one or two houses which sheltered a patrilineal lineage. With the intensification of contacts with the agents of national society, villages came to consist of houses that sheltered a nuclear family from different lineages.

This movement of concentration and dispersion, ordering and re-ordering is, in part, regulated by kinship relations (where the ‘owner of the house’ brings together a group of agnates); cycles connected to hunting and gathering; political differences and disagreements; besides contact between the Indians and national society.

The situation after contact with the Funai made the balance of political relations even more unstable, mainly due to the agglutination of nuclear family houses around the posts, along with the difficult relation of the Cinta Larga with the cities of the region, and the invaders of the territory – such as timbermen, prospectors, and other intruders -, with whom the group often maintained trade relations. Given this situation, some time ago, the solution that many Indians found was to sign contracts with timbermen and prospectors opening up the area to timber, gold, and diamond extraction. When the group did not reach an internal agreement on these commercial accords, new fissions occurred. But, even when a consensus is reached and the group as a whole agrees with such enterprises, dispersion continues. This being so, the money obtained from the transactions makes several young couples decide to establish houses in the cities of the region where they reside, with non-Indian wives, visiting the village from time to time. In all these situations, the values that traditionally sustained the prestige of the chiefs were changed.

Kinship

Even though it is not entirely without a certain dose of competition, the relation between brothers is openly marked by solidarity and familiarity. And generally, one of these brothers has a certain ascendancy over the rest, being recognized as zábiway of the area.

Filiation to the divisions is, by rule, strictly patrilineal. There are still individuals to whom double filiation is attributed, on the grounds that two men, from different divisions, participated in the individual’s conception, because both had sexual relations with his mother. They are, as they say, “mixed”. Thus a person could be Kabân and Mâmgip at the same time. Double filiation, however, is not transmitted to their children, who will only maintain the preponderant division of the father, traced through the father’s mother’s husband, thus remaining obscure secondary filiation derived from extra-marital relations. That is, a “mixed” Kabân/Mâmgip man thus contributes to the child only through the Kabân quality, which is the division of his “true father” (zóp teré), husband of his mother.

Naming

The naming system delineates a certain field of social life, centered on the domestic sphere, which consolidates ties of consanguinety and affinity. For the Cinta Larga, in contrast with the Suruí (Mindlin 1985) and the Zoró, naming does not provide a system for addressing people, a role that is left to kinship terminology, the rules of etiquette and, with unexpected importance, to nicknames. In general, the “true names” are only known by close family members and people of confidence. On the one hand, they are signs of individuality, and, on the other, an index of intimacy; the “true names” of the Cinta Larga are to be kept secret, and are for that reason removed from daily life, they are the set teré (“secret names”). In daily life, other forms of identification are used, also representing certain slices of social life, highlighting certain relations, certain contexts.

At birth, the child receives its first name: if it is a boy, from his kokó (maternal uncle) or from his kiña (paternal grandmother or grandfather), if it is a girl, from her zobey (maternal grandmother or grandfather). It is worth noting the individualizing character of the names: they translate a characteristic or some personal, physical or behavioral mark. For example, Oy Páiáy (“owner of poison”), Dáiéy Akára (“killer of the civilized”), Oy Pereá Tiri (“man who is a good animal killer”), Poposãmpirakíra (“bird hunter”), Jápã Goroey Aká (“many arrows to kill”) and the Oy Ãndát Kabira (“small-headed man”), are names for men. And Zêgina (“fertile”) and Pãgópakóba (“who learns to speak”), for women. During childhood, the father or the zábiway of the village – perhaps, other kin as well -, will be able to give a second or third name to the child, but inspired by the circumstances or things that have happened in the child’s life. Among the chosen names, while they are individual marks of identity, nothing prevents the occurrence of homonyms.

There are other indications that, in the Cinta Larga system, the principle of consanguinety constitutes a privileged model for expressing social identities of various orders, for example patrilineal divisions and local groups. In particular, the Cinta Larga think of the very notion of kinship as consanguinety, or more specifically, germane relations (the relation between brothers of the same father and mother). There are two ways for asking about the relation between two people: Me ã te zá kayá ("How do you call him ?"), which underlines the classificatory sense of kinship, and Tet êzâno ("Is he your kin?"). The word zãno, which in this case serves as the general term for kinship, is, in a more precise context, the very word for “brother".

For the Cinta Larga, fertility is not an innate quality of women, but is due to the action of the divinity Gorá, who enters girls’ vaginas, when they are still in the crawling stage. Paternity, on the other hand, is attributed to all those men who “helped to make the child”, that is, who had sexual relations with the woman during her pregnancy. Given this, the mother, will be obliged, at the moment when the child is ready to understand, to tell him/her who are the other “fathers” in order be able to treat them correctly, píípa.

Marriage

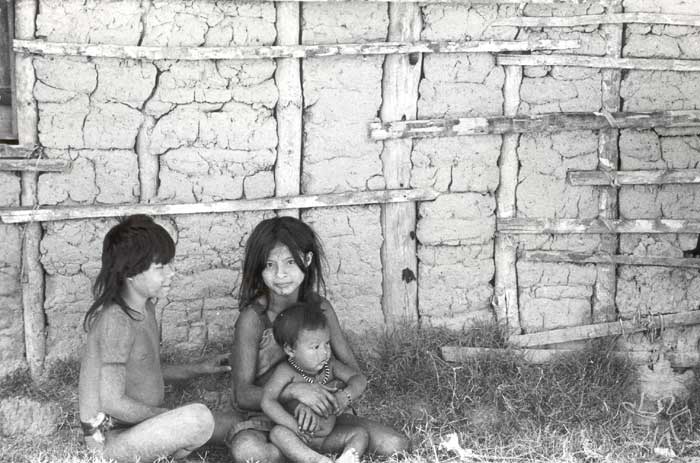

Girls are accustomed to marrying, for the first time, between eight and ten years of age, since the girl’s husband’s mother – according to the preferential marriage choice, the husband’s parents and maternal grandparents, from the woman’s point of view, coincide – will take charge of her education, a task directly connected to the husband. This happens because of avuncular marriage, between a maternal uncle and his niece, since in this type of marital union, for the spouse, parents-in-law and maternal grandparents are the same people.

Going to live in the husband’s group (patrilocality), she will continue for several years after, to play with the other children, and will only begin to assume domestic responsibilities (cooking, gathering, weaving etc.) after her first menstruation. At menarche (her first menstruation), which is ritually marked by a period of seclusion, there will also be sexual relations between spouses. It is interesting to note that, as a sign of passage to a new phase, husband and wife usually paint their bodies with genipapo: zig-zags, lines and points, on the face, a typical pattern, formed by a broad horizontal line and points.

At times, some girls go from one husband to another, and in certain cases they return to their parents, before they have consolidated a more stable marriage – which frequently happens with the birth of the first child. For example, a Kakin woman of the Aripuanã area was first given to a Kâban mother’s brother (maternal uncle); he in turn gave her to his oldest son, but, later, she married a half-brother of this man, with whom she had children and has stayed with him.

On the other hand, marriages of young men with older women, widows or wives of polygamous kin are common – whether because their sisters still have no marriageable girls, or for other reasons, the union of young men with young girls is rare. Inexperienced and with little prestige, when they think of looking for spouses in other villages or distant areas, the young men always ask for help from their eldest kin: this intermediary goes to speak with the father, brother or husband of the betrothed girl, and chants a “ceremonial speech” on behalf of the young man. An indirect way, with the same results, is marriage with one or more of the father’s wives (with the exception of one’s own mother), which, sometimes, takes place because of the displeasing recognition of a de facto situation, that is, the sexual involvement of the son with that woman.

In their alliance system, avuncular marriage (marriage of the daughter with the mother’s brother) has a special place. The Cinta Larga formulate the rule in a very clear way: “good marriage”, they say, is with the sister’s daughter. “With the daughter of my sister I marry”, is the lesson of the myth told by Pichuvy (Cinta Larga informant of João Dal Poz), in which the brothers were convinced by the sister’s husband to wait for the birth of their niece, in order to marry and live with her.

“He said that the first had a wife, three brothers of the wife and another Indian husband of the woman. The Indian wanted to have sex with the woman. Her husband said:

-You can’t have sex with that woman! She is your sister- thus he said- I will make your wives! When my daughter is born, then you marry her...live with her.

For that reason, the Cinta Larga marry with the sister’s daughter.

Polygamy

Polygamy is widely practiced by the Cinta Larga, and in a variety of arrangements. In general, the wives differ in age, when adolescent girls are incorporated to the family as second or third wives. It is very common, for example, for a man to take in marriage the youngest sister of his wife, or a classificatory sister of hers. To marry with a widow allows a man at times to receive at the same time her daughter as a second wife. Generally speaking, the number of wives a man has served as an index of prestige, political strength and, in a certain sense, wealth – although polygamy is not, among the Cinta Larga, an exclusive right of the chiefs or “owners of the house”, zápiway, they are in fact the principal beneficiaries.

Marriage strategy takes various forms and alternatives. The relations between the sexes, despite these facts, is far from being an aleatory process; on the contrary it is the result of the play of interests and power which is reserved to the men. As a corollary, it is called “woman stealing”, that is, the involvement and later flight with someone from another community, Cinta Larga or not, without the consent of the father, brother or husband, which upsets the life of the community, for it puts in question male authority, and oftentimes leads to war. The women are, declaredly, the pretext or pivot of almost all the conflicts. But these conflicts are settled as “confrontations between men”, since they are perceived as disputes of interests of groups led by the men. And, in this sense, “to exchange women” could be the beginning of a peaceful period of living together between groups, settling pending differences by means of a process based on reciprocity.

Socialization

It is known that the birth of a child is the beginning of a strong, marked time, for the married couple and the family: it involves numerous risks, demanding all types of care. In the Cinta Larga case, the liminal period is explained because what is in question is the separation between men and animals. A period devoted to shaping the social being of the child, they make the child go through herbal baths, massages and orations, they give it a name and “converse” constantly with the newborn. As for the food restrictions, this is a way of creating a univocal relation, necessary for identifying the child as a member of society.

The process of raising individuals involves essentially the constitution of an independent and self-sufficient personality. Until three or four years of age, the child is an inseparable companion of the mother. When it already moves and speaks with agility, the child joins up with small groups who imitate the adults in the gathering of fruits, in the capture of small animals and fish. The result is the formation of a light and somewhat turbulent gait, which stimulates the readiness to react to any fact that is displeasing to the individual. In general, a youth of around 16 years old best demonstrates this behavior. Unafraid, the Cinta Larga youth appears to accept no limitation, imposition or orders from anyone. He knows how to ask for what he wants directly, straight to the point, and no-one is subservient or a flatterer. Little by little girls and boys dominate the work techniques that apply to each sex, preparing themselves for public life.

The hunting style of life of the Cinta Larga can even be seen in infancy. From the time they are small, boys walk around all the time carrying their little bows and arrows, almost always chasing after lizards and butterflies. When they are older, they accompany their fathers on hunts, and in adolescence they go hunting with their companions, little by little collaborating in providing meat for the family.

After they reach seven years of age, they are submitted to the perforation of their lower lip, where they use as adornment a small stick of tree resin. The girl enters seclusion in her own house during her first menstruation. The boy, to the extent that he is successful in the hunting expeditions that he participates in, in the company of adult men, and, in the past, when he successfully participated in war expeditions, goes on to compose his own songs that tell of his success. Finally when the man marries with his sister’s daughter, thus passing definitively into adult life, this passage is marked by the ceremony of delivering ritual presents (richly adorned arrows) to his wife’s father, and by his commitment to take care of and treat his spouse well which is recited in a discursive dialogue that he has with the father of the bride and the classificatory parents of the bride.

Cycles of production and production of cycles

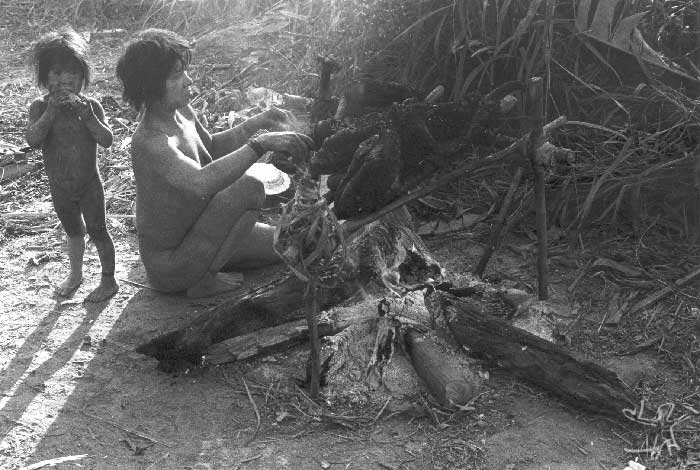

In general terms, the economic life of the Cinta Larga is organized along three dimensions: the sexual division of labor, the opposition between village and forest and the alternation of the seasons.

In the rainy period, activities are concentrated in the village; they are dispersed in the dry season. In the forest, predation; at home, the production of food and artwork. The men, excellent hunters; the women, cookers. Better said, the dividing lines, in practice, do not seem to be so exact, and much mediation and versatility permeate the daily tasks. It is not rare to see a man splitting firewood if there is meat to be smoked on the jirau, even if his wife doesn’t have an infant to take care of. Never, however, does a man weave cotton or make chicha, nor does a woman take a bow and arrow to hunt.

The Cinta Larga call the annual cycle gao, which in a strict sense is the dry season (July-October). The wet season is zoy (January-April) – translated as “rain”. The intermediary periods are called mãgábiká, “time of the garden” (May-June) and gao weribá, “end of the dry season”, or “end of the year”. The economic and social activities are unequally distributed in relation to these four periods.

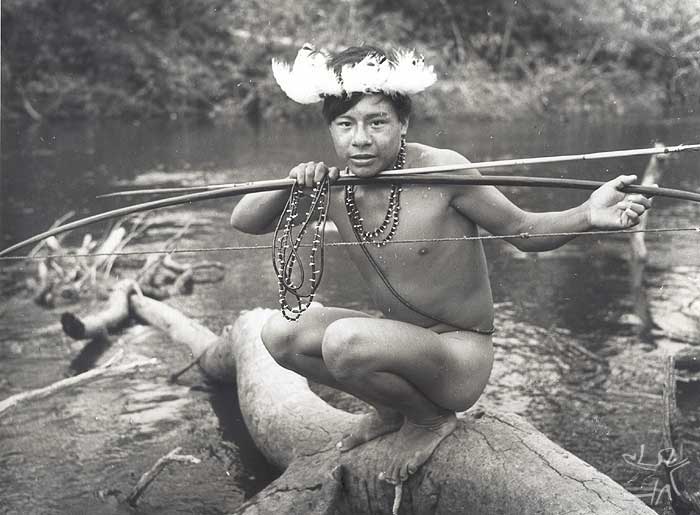

Fishing

The Cinta Larga make special arrows (long wooden shafts, with no blade on the tip), to shoot at fish, from the river or streambank. These days, they also fish with nylon line and hook. Although they fish all year long, it is in the months of November to January, when the rivers rise again and the fish ascend, that fishing (borípey) gets better results, principally in the pools and rapids. In the Aripuanã area, they are even able to catch piranha, and, on the rio Branco, surubins during the dry season.

Instead of large rivers, the Cinta Larga fish on the small streams, where they take advantage of the ecological variation in the dry season months, with light water currents and many pools where the fish hide. That is when they go out to camp and put timbó in the waters.

In these camps (gerep), organized by two or three families, during the months of August and September, they live what appears to be the ideal Cinta Larga way of life: plenty of food (fish, honey and everything else that can be found), temporary and precarious order, much improvisation and freedom of movements. It is in the forest that the Cinta Larga feel at home: “To sleep in the woods is good”, they would confirm. At a distance of a few hours walk from the village, it is there they spend about a week, before going back to the village; days later, with a new load of manioc and yams, they set off in another direction, to a new campsite.

To put plant poison, timbó, in the water, they choose certain places propitious for this activity: large pools, still water, many fish. Itaká (“to beat on the water”) or bókobóko (onomatopoeic word) is, in general, an activity that demands the cooperation of several men. First, they cut the vine (dakáptapóa) and tie it in bundles; sometimes they also use the bark of a certain tree, packed in baskets of palm leaves. They then start to beat the fish upstream, which goes on until mid-afternoon. The fish then begin to turn back and they are shot with arrows or caught by hand, but it is on the following day that the waters and the banks, sometimes over a kilometer or more, will be clogged with dead fish. Children, women and men – all participate, tieing them up on fishing lines. They are then roasted on jiraus, the smaller ones in “packets” made of fresh babaçu leaves.

Agriculture

They spend very little time on agricultural practices, which are even considered secondary when compared with the adventure of hunting. Thus, they do only what is absolutely necessary: cutting and burning by the men, but planting with the help of the women. The gardens are almost never cleaned or weeded, which makes the task of harvesting difficult, gradually done by the women.

Agriculture is, on the other hand, the responsibility of the married men: a man without a wife, normally doesn’t have a garden. The initiative and the effort are taken by the owner, but there exists much cooperation among all. Even though each married man has his own, the largest garden of them all is generally that of the zápiway, “the owner of the house”. It’s as though, in a certain sense, the dwelling and the garden were inherent to the function of the chief – and, as we shall see in the item on “festivals”, house and food are among the ritualized elements in the festival. It is worth remembering that, to invite kin and allies to the festival, it is necessary to clear gardens that are much larger than usual, obliging the host village dwellers, the year before, to double their agricultural efforts.

After choosing the area, the “owner of the garden” begins to cut the underbrush at the end of May. In this phase already, as well as in the phase of cutting the larger trees, which lasts until July, and planting, which begins in September, he always invites several men who are available, married and single men of the village, or whoever is passing through the village or is visiting.

The work in the gardens, which is done in the mornings or at the end of the afternoon, happens in a discontinuous way, interspersed with hunting expeditions, fishing expeditions, camping, journeys, and days of rest.

Corn (mék) is the first to be planted; after awhile, varieties of manioc (xíboy), yams (moñã) and sweet potatoes (mãkap) and one other starchy rootcrop, marãjía, which is eaten raw and the seeds of which look like big beans. Today, they also plant rice, beans, papaya and banana.

The Cinta Larga do not plant the so-called “wild manioc”, nor even have a process for making manioc flour – a typical food of the historical Tupi and other peoples of this linguistic trunk. In view of this, the possibility of storing foods is reduced: except for corncobs, which are stored in corn cribs in the garden or in tied-up bundles in the roof of the house, the harvesting of other agricultural products depends on domestic consumption. They harvest their gardens in a peculiar way: the manioc plants, for example, are not pulled up. The women dig with a special stick and take out only the largest roots, leaving the others intact.

One of the principal results of cultivating the gardens is “chicha”, a daily food: of manioc, yams, corn, or sweet potato, it has the consistency of porridge and is reputed to have a highly nutritive content for, they say, it strengthens and “fattens” the consumers. In this cuisine, there is at least one more elaborate recipe: the women cook pieces, pound them, chew them, and add condiments – when in season, honey is almost always one of the ingredients. Different from the Surui “makaloba” and the Zoró chicha, that of the Cinta Larga practically is not fermented, being consumed on the night of the same day and on the following days.

Hunting

Hunting is the activity that most interests the Cinta Larga: they devote themselves assiduously to it and it is one of the preferred subjects in conversations among the men. They spend numerous afternoons in their “shops”, small camps about two hundred meters from the house, in the cool forest, where, alone or together they make bows and arrows. Precious objects, the hunters do everything to recover the arrows they have shot, taking precautions on aiming or scaling, at which they are quite agile, the highest trees.

Hunting is practiced throughout the entire year, however, the results of the expeditions vary, there being a very weak period – perhaps due to the migration cycle of the animals – at the height of the dry season (August-September). Almost all the animals - birds, mammals, fish and reptiles, but only the boa constrictor among the snakes – are used for food. The ones most often killed, certainly in terms of numbers, are the varieties of monkeys and birds, such as the jacu, jacutinga and curassow. Peccary, wild pig, and tapir, however, are greatly appreciated. And the presence of fat is what is most looked for: when someone is cleaning the game, they soon ask: Tét kamdák (“Is it fat?”).

Hunting, in general, is developed on habitual trails (bé), each hunter exploiting a region near the village, in a maximum radius of 15 kilometers around it; the trails are periodically explored by the hunters.

Night hunting was not practiced traditionally, but the introduction of firearms and lanterns has been changing this pattern. The Cinta Larga, on the other hand, are experts in building hiding-places (digit), as they are in “calling” the animals, imitating their whistle or cry, with perfection. At the end of the rainy season, they are accustomed to tracking down and asphyxiating the paca and the armadillo in their holes, fanning smoke into the holes. And in the dry season, they look for the alligator in the streambeds, pulling it out from its lair.

The adventure of hunting, however, is not reduced to its technology nor to personal skill, but rather it presupposes magical expression, dream symbolism, and a food diet – these are the elements that denote an essential relation between hunters and animals, linked to their cosmology. Truly an ethic for guiding the hunter’s steps, it obliges them to make careful preparations before encountering the victim, through a process that assimilates the hunter to his game.

Arriving from the hunt laden with game, the hunter, in a somewhat theatrical gesture, throws the pasápé (an improvised basket made of palm leaves) in the middle of the house, or leaves it at the entrance of the trail for his wife to fetch. Normally, he has already cleaned and quartered the game, leaving the game cut up in appropriate sized pieces. His wife unwraps the bundle and, if necessary, removes the hair from the hide, before putting the pieces in the pot.

In the preparation of meat, be it game or fish, cooking is the principal technique of Cinta Larga cuisine. While fish is quick to cook, meat requires a slow burning, which begins at nightfall, lasting from five to six hours, in the case of larger animals. Fearing the evil effects of the bloody remains, the meat is boiled until there is not a single trace of blood left. A crucial rule of eating, avoid any contact between blood and food - the Cinta Larga were horrified, for example, with our habit of putting small cuts on the fingers into the mouth. They say that the blood, if ingested, brings on serious sicknesses (fevers, headaches, malaria etc.). For that reason, they carefully wash with sand the knives used for cutting the meat, and do not by any means allow bloody meat to be put in the baskets that they use to eat.

Among the Cinta Larga, in principle, each family has a kitchen: husband, wife, or wives and children form a unit of production and consumption. Each one of them, in the corner that he/she occupies in the village, lights his/her own fire, to cook and, at night, to warm themselves. Self-sufficient, but not impervious, the families represent the units of food exchange, in their daily version. Regularly, they are articulated in a network of circulation of foods that includes all of the village dwellers, as well as the visitors. All the time, small presents or things to nibble on go from one man to another, one woman to another. Always courteous, they do not hesitate to settle into a hammock and offer cooked yam or some other morsel, even to a co-resident who has only approached to chat. Along with this series of polite gestures and informal demonstrations of affection, another circuit stands out, this one more conventional. Strictly speaking, a markedly male etiquette, which distinguishes two foods, meat and chicha, the distribution of which is considered obligatory. Along with that, there is a subtle play of formalities and shyness, or we would say, rules of good manners to be observed in relation to food – in making, giving, receiving and eating.

Gathering

Among the subsistence activities, the gathering of forest products can represent, above all, occasions for eating. It is quite true that forest fruits, such as cacau (akóba), pama (abía), abiurana (dedena), jatobá (madéa), ingá, patauá (oykap) or pequi (bixãma), although much appreciated, are no more than delicacies, seeing as how they have little influence on the diet. The important items are castanha nuts (mãmgap) and honey from bees (íwít), for which they organize expeditions to the forest which bring together, on normal days, two or more families – men, women and children. These expeditions are like excursions, full of happy and pleasurable moments.

The method for gathering is the same as for the hunts. If someone locates a beehive, days or weeks before, while hunting or on a trip, he will be the béxipo to organize the expedition with the others: he cleans the trails with machetes, cuts down or directs the cutting down of the tree, opens the beehive and distributes the honeycombs and the honey, and gathers the greater part for his family.

On these gathering expeditions, the men walk in front carrying their arms, alert for sounds, signs or movements that indicate the nearness of some game animal; further behind, at a distance, are the women carrying their babies, baskets, pots and axes, keeping step with the older children. Without getting lost, they march on the – at times, almost imperceptible - trail of their husbands – a footprint, a broken branch here, a turned over leaf there. Besides that, another interesting fact is that, when they walk in the forest, the Cinta Larga rarely change the initial order of the Indian file: if they stop to rest or slake their thirst in a stream, on returning to the march, they fall into place, obsequiously, in the same order as before. As a rule of good manners, the group forms a hierarchy in walking, and reveals with that, once again, a form of organization of the collective activities that has the bexipó as their main coordinator. If he is the leader on going to the place for gathering, on returning, positions are inverted, and he occupies the last place in the file. First or last, but always a unique, necessary place, a focal point.

Among the types of honey used by the Cinta Larga, they prefer that of the tame bees. They confront aggressive bees, but which do not sting, such as the “xupé” (arama), courageously and festively, with laughter and shouting. The scene of such a confrontation suggests, although this was never explicitly stated, a parody of the warrior combats: they advance with straw torches alight, balancing on the trunk of the tree that was cut down, to throw the torches over the fallen beehive; making much noise, they do not retreat despite the swarms of angry bees, which stick to and bite the body and in the hair. Once the beehive has been opened with an axe, distribution is made around it quickly, in large pieces. Only then do the men withdraw, running, and go to taste the honeycombs with their wives and children, at a distance. Little by little, then, the pots and paxiúba recipients (daroíp) are filled up with honey and pieces of the beehive.

In the same way, in the rainy period, two or more of the families go out to break castanha nuts, going to the known castanha groves. There, men and women freely gather the chestnut burs scattered over the ground – in anticipation, in the dry season they set fire to the creeping vegetation under the castanha trees, to facilitate the search. Highly appreciated, they eat the nuts all the time, as a food complement or not. They drink chicha at the same time they chew nuts – kindly, they offer shelled nuts to invited guests. And, pounded and roasted in straw shells, the nuts make a delicious dish called mâmdík.

Tidbits which are appreciated in the seasons when they appear, insect (Coleopters) larvae are gathered mainly by the women; these are found nested in babaçu and tucumã nuts, and also Lepidoptero larvae, which are rolled up in leaves. During November, they all go out to gather the tanajuras (mamóri) – female saúva – which fly out from the antholes. Both larvae and tanajura are fried for eating.

Outside of these food elements, there is an extensive list of raw materials for which they make excursions into the forest: a wide variety of leaves and roots for remedies; açaí, babaçu, and tucum straw for baskets; tucum and other fibres for string and cords; nuts and xikába for collar beads; grainy rocks to scrape the collars; tabocas for transversal flutes and reed flutes; taquaras for arrows; pupunha saplings for bows; woods and enviras for the most diverse uses; the sheathing part of paxiúba leaves to make storing-places for instruments and feathers; roots of the paxiúba saplings to make scrapers; resins for lighting etc.

Another list would include several new materials and “imported” products from the cities, which are integrated to the daily lives of the Cinta Larga: umbrella ribs as perforators; aluminum and plastic materials for beads and collar; pieces of metal as bead-cutters; cans poked with holes as sieves; bottles for putting honey; knives, machetes, axes and hoes; nylon lines and hooks; rifles, clothes, sandals and suitcases; lighters and numerous other items.

Division of labor

Outside of these, their tasks are quite clear. If they are not cooking or harvesting in the gardens, the women occupy themselves, indefatigably, in the tasks of artwork. At any time, one can see them on the plaza or inside the house spinning cotton, breaking nuts, or weaving little straw baskets. They make the following items: sleeping hammocks (iñi), armbands (nepóáp) and bracelets (arapéáp), hammocks for babies, shell collars (bak’rĩ), vine collars (amoíp), womens’ belts (xiripót), baskets (adó and datía). Ceramic pots (bosáp) were quickly substituted by aluminum buckets, and are no longer produced.

Male labor on the other hand is characterized by discontinuity: intense efforts in hunting or in the garden are spaced between hours or days of rest. At home, they sleep in hammocks, eat or drink chicha and make: headdresses, flutes, lip adornments, piercing instruments, mortars, troughs etc. But, visibly, it is the bows and arrows which are the main articles of the men. Beyond what has already been mentioned, it is worth mentioning that, although they are articles of personal use, the quantity of arrows in a village is also among the concerns of a zápiway. Inviting his companions to jápâga (“make arrows”), getting them together in the shop, getting all the necessary materials (taquara bamboo for the points, feathers, string, wax), putting these at the disposal of the others, supervising the work and inspecting the quality of the arrows, are forms of stimulating production. Others are the expeditions to look for taquara, in parts of the low forest within or outside their areas. In particular, the festival would be an occasion for making a stock of arrows, and in this sense it is one of the reasons, among others, for a zápiway to organize them.

After 1980 they began to work in rubber extraction and gathering nuts seeking to commercialize these products. The isolation of the area, difficulties in transportation and small scale of production yielded an insignificant monetary return.

Male activities include hunting, the cutting of the trees and preparation of the soil for planting, the making of arrows, bows, flutes, feather ornaments, rubber extraction, fishing, building of the house and cleaning of the forest around the village. The women gather, spin cotton and tucum fibre, make hammocks, ceramics, take care of harvesting the gardens, preparing the daily food, producing collars and bracelets. And, as was said, men and women gather honey, nuts, and work in the planting of the gardens.

No doubt, the presence of the diamond mine on Cinta Larga lands is what, in fact, is presently moving the local economy, producing a group of chiefs who have access to the principal Western goods, obtained in trade for the diamonds exploited by the prospectors.

Material culture

Indigenous artwork includes the making of baskets, bows, arrows, collars of tucum nut, wristbands also of tucum and monkey teeth, feather ornaments for the head and arms, sleeping hammocks, straw or jaguar skin adornments, flutes, mortars, spinning implements, piercing implements, resin adornments for the lip and other less important ornaments.

For war, the Cinta Larga painted themselves with jenipapo (wésoa), using animal or plant motifs and, in the past, they cut their hair very short. They wore eagle feather crowns (katpé), thick collars of shells (bak´rĩ) around the neck and crossed over on the chest (nakósapíap) and the typical belts (zalâpíáp), made from the innerbark of the tauari tree (wébép). They also ornamented themselves with rolled-up buriti straw (wébay) on their arms and legs. Their weapons are bow and arrows and the tacape club, utilized in specific situations.

The bows (matpé, oval shaped, are about 2 meters long, and are made from the young pupunha trees (jobát). The arrows (jáp), on the average 1.80 meters, consist of a shaft of taquara, into which is inserted a point in the form of a knife, made from a kind of taboca, and, on the lower extremity, eagle wing or curassow feathers. The bows are quite resistant and demand of the archer training and physical force. There are various kinds of arrows, for birds, monkeys, large-sized animals and fish, but they are always made with much care. Some, with the shaft part made of wood (ipép), toothed and ornamented with plaits of peccary hair (jápsík), in lozenge patterns. The tacape (sóká club is similar to a short sword, a meter long, made from the pith of very hardwood, black or red, and the handle is ornamented with red and yellow feathers.

The tacape club, which today has been substituted by the machete (big knife), served in lightning or sudden attacks. If, by chance, they got into an argument with a visitor (akwesotá- “speak badly”, the Cinta-Larga say) due to “woman jealousy” or for some other reason, and decided to kill him, they would approach the victim with the club hidden behind the back, and when the chance occurred, they would strike a blow on the adversary’s neck and, when he fell, they would thrust it into his chest. This type of homicide was very frequent, giving rise to constant hostilities among the various groups.

Still among the warrior techniques, the Cinta Larga use several kinds of poison to put on the eyes of the enemy, blinding them temporarily. Mórat is the general term for classifying these, the same term used for “hunting medicines”. Of these mórat for war, it is possible to single out the bébésirík (“pig skin”) and the wásakoroyáp (“tapir womb”), both extracts from treebark.

They also know other powerful poisons (pósot- “bad thing”), that can be added to the food of their adversaries, causing them death. This technique, however, is practically restricted to use among those who eat together, those who share the same social space. Further, it is a form of homicide associated with the women, not only due to a food metonym, but also because it is the only death-dealing weapon to which they have access – and which serves to eliminate undesired rivals or spouses -, even though it is not exclusive to them.

As plants are very often used as a weapon of vengeance, it is important to recall that witchcraft accusations are constant among the Cinta Larga. Mutual accusations are responsible for aggression among the Indians, and, should deaths occur, this sets off a series of retaliations and war expeditions. Several kinds of poisons are used against the women to cause fatal hemorrhaging, those that cause abortion and others their death. To be used against anyone, there is Po sut, poison that, when mixed in the food of the victim makes him/her lose weight progressively until death.

Cosmological aspects

From the ethnographic point of view, the Cinta Larga are one of the few groups affiliated to the Tupi linguistic trunk who have not incorporated tobacco into their culture. Thus, the curing rituals involve the recitation of efficacious words, the shaman’s placing of hands and breath. This ritual finds lesser expression in the overall set of Cinta Larga ceremonies, in the same way as the rituals of female seclusion and the piercing of the lower lip of the children. They are minor celebrations when compared to the festival of the bebé-aká (see the item Festivals).

Basically, they use certain “medicines” which are specific to the animal species they wish to kill and that propitiate the individual success of the hunter. Classified as mórat, a term that is also used to refer to poisons used in war, these “medicines” are extracted from plants which are associated by the “law of similarity” to the animal sought in the hunt.

A few examples: To hunt tapir, there is a wild bush the leaves of which have the shape of the foot of this animal- wásapí, “tapir foot”, is the name of the plant and the medicine. The leaves are soaked in buckets full of water, at the riverbank, and then the mixture is drunk causing vomiting, which “cleans the insides” of the hunter. The medicine for hunting peccary has the same smell as this animal, as does the medicine for the monkey called macaco-prego. The root of the plant is chewed and spat onto the hands, arms and chest, and rubbed over the body.

Dream images, likewise, have symbolic relations to animal species, and are interpreted in standardized ways. To dream that one is crossing the river, underwater, means that the hunter will find a tapir. To dream of a woman means a female tapir, while homosexual relations indicate a male tapir. If one dreams of taking out chiggers from the foot, the hunter will kill an eagle – and the explanation is that, as it eats, the eagle holds the meat in its claws, at times already infested with larvae. Dreaming of living in an old house means armadillo, but if one dreams of “walking with a light at night, like a firefly, it’s a jaguar!”. Dream symbolism is formed around predator and prey images.

Among these practices we find a taboo: the consumption of meat by the biological parents whose children are in early infancy. This prohibition more strictly affects the mothers. In the first days of the child’s life, the mother’s diet must be restricted to plant foods, honey, and, if there is any available, alligator meat and fish that are permitted; shortly after, jaguar, wildcat, tayra, giant armadillo, coati, jacutinga and partridge can also be eaten. Regarding tapir meat, nothing more than small pieces can be eaten by the father.

These concerns are progressively abandoned, according to the stages of the child’s development: until it is “a bit more firm”; when he/she begins to sit, to walk and to speak. In the first three weeks, the child’s father even suspends his hunting and restrains from doing heavy chores. The older women take special care that the young people correctly observe the norms: the argument is that, by carelessness or gluttonry, a father or mother who does not respect food taboos will cause sicknesses or even convulsions (pãdágña) in their child. The list below indicates the kinds of meat that are prohibited and allowed after birth, some of these being taboo for a long time, for example the peccary, which the father can only eat when the child begins to walk, and the coatá, the last to be permitted, when the child begins to speak.

Mammals

| Prohibited Meat | Permitted Meat |

| Coatá (basáy); big-bellied monkey (xakát); macaco-prego - monkey (basáykip); guariba monkey (péko);ko), cuxu(pprego(kguariba, cuxucuxu cuxuí (básaypip); peccary (bébékót); deer (ití). | paraguaçu (parapxíp); sloth (alía); jaguar (nekó); wildcat (nekókip); tayra (awaráp); boar (bébé); tapir (wása); giant armadillo (málola); coati (xoyíp); cutia(wakí). |

Birds

| Jacu (tamoáp); jacamim (tamaríp); mutum (wakóy); arara-vermelha (kasít); arara-cabeçuda (ãmiâ). | Jacutinga (pixakót); nambu (wañã); gavião-real (ikônô) |

Fishes

| Piranha (iñeñ); mandi; surubim (koledé); poraquê (goyâna). | Other species (bórip) |

Reptiles

| Alligator (wawó) |

The high value that the Cinta Larga place on individual self-sufficiency makes them always careful about bodily health. At the first signs of not feeling well, the individual takes to his/her hammock and seeks to identify the causes of discomfort. He relies on the support of a wide gamut of knowledge and practices to help him in eliminating sickness. Out of the many hundreds of plant species that are found in the forest, several have been selected for their special properties in assuring protection through cures, prevention of diseases, or even by permitting the development of abilities that directly or indirectly help in maintaining good health. This a form of knowledge which all share, and which increases with age. By way of example, we cite several uses of plants which are regularly used: to increase female fertility; to guarantee male potency; to ensure a good birth; to avoid abortion; to diminish uterine contractions; to purify the parents of a new-born; for the well-being of a newborn; to avoid the constant crying of the newborn; to make the child sleep well; to make adults sleep lightly; to prevent the child from biting his mother’s breast while he is nursing and many others.

Once health is guaranteed, a set of plants meets the needs of another sector: the good performance of the man while hunting and the use of weapons. There are even plants used to attract animals the leaves of which the hunter rubs over his body.

Creation myth

The universe is seen through the prism of unity. The creation myth is a detailed account of how Gorá created human beings, members of different tribes who populate the region and conferred on them specific identities and characteristics. Animals, birds and other living beings were created through the transformation of men; some became jaguars, others tapirs etc., all through the work of Gorá. Gorá and other minor heroes of Cinta Larga mythology are responsible for all that is positive in the social and cultural universe. The counterpart of these beneficial acts of creation is a spirit that inhabits the forest and which incarnates the dark side of existence. Its name is Pavu. It wanders through the forest in search of victims and, as soon as it comes upon a solitary hunter or anyone passing through, he launches his mortal attack. No-one resists its power, and, from this encounter, victims get fever which is inevitably followed by death.

Festivals

Festivals occur during the dry season. Preparation for the festivals takes a year, or a little less, while their realization, around a month. In order to hold a festival, it is necessary for the house-owner, that is, the host (íiway [owner of the chicha, fermented beverage], or mêiway [owner of the plaza]), to have planted a large garden of corn, manioc or yams – the choice of the produce to be used in the preparation of the drink is made by the guest of honor. Besides that, he has to capture a young animal to be sacrificed, preferably a wild boar. Peccary, monkey, macaw, quati, curassow, jacamim and others – or these days, even chickens and cattle – equally serve for the role of victim. Once captured, the animal receives a name and is raised by the wife of the íiway, or by his daughter.

The festivals are ritually connected to Cinta Larga sociology, since forms of ritual conduct refer to forms of daily conduct, although in a way that we could call the inverse.

There is no generic name for this ritual: the Cinta Larga say íwa (to drink chicha), ibará (to dance) or, more rarely, bébé aka (to kill pig). Such references sum up, in a way, the ritual program: to drink chicha, dance and kill the animal. And, from the beginning, they have to do with an invitation. The building of a new house (maloca) or a warrior expedition were the principal motives that traditionally led a zápiway (houseowner) to plan a festival. For war, the ritual enlists allies, organizing the attack, and then, commemorating the deeds of the warriors. For the house, it represents a “homage” to the zápiway of another village, who assumes the role of “guest of honor". In one case, the festival inaugurates a social space, in the other, on the contrary, it marks a rupture in social ties.

The festival can be understood as an invitation to kill this animal, whose name is announced to the guests by the host’s messenger. When that happens, the house, garden, and domesticated animal together provide the necessary material conditions for the ritual. But it is the guests who are the principal social sine qua non, for it is they who “make” the festival. A sociological premise of the Cinta Larga ritual, reciprocity between host and guests orders relations between people and villages, since one festival involves another in return: on accepting the invitation, the invited guest ideally commits himself to organizing a new festival the next year in his house. In the words of Taterezinho (a Cinta Larga):

It’s the other who gives afterwards, another, another village will give the festival another year. The one who gave this year won’t give the next year. There has to be an other, another group that does the fest. Then he invites the other just as he was also invited.

Structurally, the invited guests take the position of the “other", a term for a virtual relation of affinity. For a similar festival, the Suruí (Tupi-Mondé) explained with clarity the relation in play and described the guests as “non-kin” or “affines" (Mindlin, 1985:48-9), who are associated with the metare (a camping site near the village where the men work on their bows and arrows). On this point, the Cinta Larga seem to establish this relation in a more “symbolic” way: they say mâmarey (má, 3rd person), "the others", to designate the visitors; while pãmarey (pã: 1st person pl. inclusive), "we", the members of the group itself.

The whole ritual sequence is based on this central opposition, which, at all moments and through very diverse forms, dramatizes the encounter of groups who are initially considered adversaries. They are ritually "enemies", therefore, who come to the festival at the invitation of the host. The invited guests arrive at the previously established time and enter the village, at night, dramatizing a warrior attack. However, they are received there with watery chicha, and not the sweet chicha that is habitually consumed, and they dance in the center of the house.

When men or families from a distant village, from a distinct local group arrive, the Cinta Larga are accustomed to dancing one or more nights, to drinking chicha and also singing. This confraternization between the two groups is part of the diplomacy of receiving guests. The arrival of visitors is sufficient motive for holding a festival, even though it is limited to only a few nights of dancing, a little chicha, which they drink with moderation, and some playful moments. In effect, among the fourteen festivals studied by Dal Poz, at least five of them simply marked the arrival of the visitors, or better, the re-encounter of two groups: the house filled up with people, and for several days the village became lively and happy.

Such journeys to visit, as well as the camping sites and the festivals, are activities which are typical of the dry season. After the clearing of the forest in May or a little later, the families circulate widely among other villages, favored by the climate and, as their only obligation, the burning and gradual planting of two gardens. This was likewise the most propitious time for warrior expeditions. The arrival of the visitors follows a certain order: they announce themselves from a long way away, playing a panpipe, the dissonant sounds of which carry over great distances. They lay their bows and arrows down by the side of the door and enter the shade of the maloca, imposing figures, dressed for the occasion – eagle feather crowns, multi-layered collars and belts of treebark. This moment is one of great theatrical presentation and, as on other occasions, the coming on stage seeks to impress the spectators.

At intervals of two or three days, the nightly dances are repeated, in a rhythm that increases in intensity and liveliness. Face to face, two lines of men dance, rivaling each other. Behind these lines several women also dance, with their hands on the belt or shoulder of their husbands, boyfriends or brothers. A set of reed flutes (tokótokóáp or wa’áp) provide the musical accompaniment for the dance choreography. From time to time, the musicians remain silent and a singer improvises verses, which are repeated in chorus. These songs, called bérewá, focus on the very social context of the festival, highlighting the relations between the groups involved. In the common festivals, they don’t mention fights or hunts, but they affirms that “all is well", that "it is good to drink chicha", or describe their journey there, the place where they live and the growth of the group, or then they recall visits and other peaceful events.

In the festivals in preparation for war, however, the songs anticipate the tactic of the warriors, but on the condition of not pronouncing the ethnonym of the enemies or that they will “attack people". The singers then say that they are going to “kill pig", "kill monkeys" or that they have left for a "hunt". Or, then, they remember the “wild” animals that they have already killed: eagle, jaguar, etc. Other times, the warrior speaks of himself as a predatory animal, a jaguar, for example. A rule of warrior discourse, the linguistic avoidance which is likewise extended to the festivals that commemorate battles and last for a long time, situates the enemies in the domain of animality and makes hunting a metaphor for war.

Festival and daily life

The ritual script clearly traces contrasts with daily practices: activities which are individualized in daily life (gathering, making chicha, hunting, eating, playing a flute, singing, etc.) are, in the ritual context, done collectively, always having someone to lead them or coordinate them. Thus, for example, beverages have a central place in the festivals; however, they are displaced by the mechanism of inversion in the mode of production, distribution and consumption. If in daily life each woman prepares chicha for her husband, in the festival it is the group of women which takes on this task. And the host, who neither dances nor sings, must personally serve it to each dancer – which is distinct from daily conduct, when the other men are simply called by the husband to altogether serve themselves from the bucket. Ritually consumed in excess, chicha is vomited on purpose in the middle of the big room by the dancers.

As ritual drink, therefore, chicha appears as an anti-food, subverting the vital function attributed to it by the Cinta Larga (fattening, strengthening the body).

The ritual program also highlights the host’s obligations to provide food. When the messenger comes to announce the festival, the invited guests put forth their requests for food, called méémã – in general game meat or fish; and, to attend to these requests, the host organizes collective hunting expeditions. On normal days, the Cinta Larga prefer to hunt alone or with only one companion. But this aspect, which is not the only one, appears ritually inverted. The cooked meat will be divided by the íiway in two parts: the first, served to the invited guests, who grab the food in the basket, behavior that offends good manners; the other, which is ceremonially delivered to the invited guest who requested the dish.

In relation to the food, the lack of moderation and the voracity of the guests are the norm. If they are hungry, they don’t hesitate to kill chickens and domestic pigs or take the food that they desire, even though they reciprocate with one or two arrows. On certain nights, they even organize real “assaults” on the stocks of food: Akoy té ma wirá (where is the food?), they repeat, while they comb all corners of the house, gathering and eating the food they find.

In the internal organization of the ritual itself, in turn, one finds curious scenes: an almost obligatory part of the night dances, young men with grotesque disguises abruptly interrupt the dancers and act out small comedies (gôji), full of obscene or repugnant humor. In effect, the expressions of opposition, present in daily life or of a strictly ceremonial nature, are multiplied at each step: owner of the chicha/ drinkers, cookers/hunters, giver of food/”devourers", women/men, musicians/singers, dancers/clowns, and are repeated in various other elements.

A dance on the final night, the one that is most awaited, precedes the sacrifice of the animal victim and engenders numerous symbolic operations, particularly gender inversions and other metamorphoses. On that day, it is the men and not the women, who go to get manioc or yams in the garden. At night, another inversion: the women open the great room where the dances take place, dancing in two lines, similar to the male dancers. Some time after, the guests enter, eagerly, and the space is once again occupied by the men, who dance and drink abusively.

At dawn, excited by the drinking and the all-night ritual, the remaining dancers ritualize a kind of “vengeance” against the host, thus paying back, as the Cinta Larga say, for all that they have “suffered” in the dances and drinking bouts during the festival. In a revealing gesture, the host is symbolically animalized by the guests: they follow his “trail” and, on finding him asleep, they throw cold water in his ear; they oblige him to then drink chicha, while they simulate fanning flames with straw fans, to light the fire to roast him.

Identified with a domesticated animal (since he is treated with chicha), the host thus suffers an extreme symbolic displacement, being converted into “food” for the guests. In other words, the host not only feeds the guests, he is the ritual food itself – and the insistent gesture of fanning the fire leaves no doubt: we are cooking, “later we eat “! A critical nexus of the Cinta Larga ritual scheme, this passage thus unveils the cannibal logic which organizes it.

In the context of the Cinta Larga festival – and also Suruí and Zoró, both of the Tupi-Mondé language – sacrifice has a central place; all ritual acts lead up to this climax and find their meaning in it. A good part of the men’s attention, before and during the festival, is concentrated on the death of the animal victim. As I have said, the invitations already point to this objective:

For that reason he (the host) did the festival. To kill the animal. For that reason he invited everyone, to eat, to join everyone together. To join together friends to eat that animal. (Taterezinho).

The guests, then, are assembled around the sacrifice – an eminently social purpose. It means setting up an alliance in which the victim plays the role of intermediary. Not a term, but a relation: the ritual death of the animal victim appears here as a symbolic sacrifice of the host himself. The gôm, the animal domesticated by the host’s group, is substituted in the sacrificial act. The vicarious function of the animal, - even though this is not explicitly stated by informants – is logically deducible. In a word: a "host animalized" by the guests will, in sequence, offer a “socialized animal” to be killed and eaten. In effect, host and victim are placed in a relation of metaphorical identity, since the first has acted the part of an animal a bit before; metonymic also, for both “belong” to the same social group.

In the early morning hours after the last dance, the guests burst out of the house shouting and dance and drink until dawn. In the morning, the host ties the animal by the feet, in front of the house. This detail would once again denote the association between the victim and the host, who was also tied up in an analogous way. The host then leads the men by the hand, beginning with the guest of honor, and positions them side by side, facing the tied-up animal (thus, with their backs to the house), and then steps back. With their bows and arrows in hand, the men dance, advancing and retreating in front of the victim. In improvised verses which will be repeated by the others, the guest of honor praises the hospitality of the host and announces the death of the animal, and, when he finishes his song, he orders the men to kill it: kaben sakirára (let’s kill it!). In an instant, all the archers shoot their arrows. At the same time, they shout that they have killed many animals, naming them: "I will kill, as I killed that deer", for example.

In this way, in the same act in which they sacrifice the gôm, the guests recall the hunt. In a phrase, the sacrifice would be the memory of the hunt. When we referred above to Cinta Larga war songs, we saw that hunting and warfare were related metaphorically, the first being a language for the other; we know now that sacrifice also touches on this same keynote.

At this moment of the ritual, the participants break out into pandemonium. It is difficult to reproduce the pride of the phrases, the cries of jubilation, or describe the exalted bearing and energetic gestures of the ritual performance. I would only say, at the risk of paradox, that they seem to be in a state of happy combat. Thus, memory of the hunt, but a war ritual.

Having killed the victim, the men turn to the host who, only a small distance away, observes the spectacle, and they communicate to him that they have killed the animal: Amoya, enaeyá sakirá (my kin, I have already killed it for you!). The air of excitement, formalism and tension that precedes the sacrifice dissolves. The guests now give their arrows as presents to the host. The dead animal is placed on leaves or straw in the same place where he was tied up and, one by one, beginning with the guest of honor, the participants in the sacrifice throw their arrows, looking at the victim or at things closeby. These are not the arrows that were used to kill the victim, they are others, finely finished and decorated, and they are thrown with some depreciative or joking comment made by the archer. The host them comes close to hear and, after, gets the arrow for himself.