Ikpeng

- Self-denomination

- Ikpeng

- Where they are How many

- MT 584 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

The Ikpeng came from the region of the feeder streams of the Xingu in the beginning of the 20th Century, when they lived in a state of war with their upper Xinguan neighbors. Contact with the non-indigenous world was even more recent, at the beginning of the 1960s, and had disastrous consequences for their population, which was reduced to less than half as a result of diseases and killings. They were then transferred to the borders of the Xingu Indian Park and "pacified." Today they maintain relations of alliance with the other villages of the Park, but nevertheless their society is quite distinct from the others. They don't wage war any longer, although war is still at the center of their worldview, not only as a motive for death but also for the replacement of the dead through the incorporation of the enemy into the group, thus also being responsible for the reproduction of social life.

Name

Ikpeng is the self-denomination of the group, but they became known through the name given to them by a hostile group with whom they came in contact: Chicão, Tchicão or Txicão. As far as the term Ikpeng, there is more than one version about its origin that is told by the Indians. Most state that this is the name of an angry wasp, the larvae of which they rub against their skin in a warrior ritual. According to several people, it is an ancestral ethnonym; and for others it corresponds to a name that was given to them by ancient enemies and which they later adopted. In any case, there is consensus that the designation Ikpeng is older and more authentic than Txikão.

Language

The first prolonged contact on record of the Ikpeng with Brazilians dates from 1964. The ethnologist Eduardo Galvão, present at this encounter, recorded a dozen words which enabled him to establish the affinity of the language of these people with the Apiaká (of the Tocantins) language and the Yaruma language of the ancient enemies of the Kalapalo and the Suyá (Galvão and Simões, 1965:24). Moreover, there are immense lexical similarities between their language and the different groups called Arara, from the region of the lower Xingu - which leads us to believe in the existence of an Arara language group in the Karib family. This language, nevertheless, seems to us to be closer to the Karib groups of northern Amazonia (Apalai, Wayana, Trio etc.) than to the Kalapalo or Kuikuro (both karib) of the upper Xingu.

Among what we understand as Arara groups - Ikpeng, Yaruma, Apiaká and Arara - there are not only linguistic similarities but also a series of similar cultural aspects, leading us to believe that their diaspora was due to separations and different migrations of groups that had once been together.

There is scant information about these groups, thus it is only possible to elaborate a summary picture of their principal cultural characteristics, such as the centrality of war to their worldview, their great mobility, the extreme fragmentation of social units and the absence of social segments beyond the extended family (strictly speaking, given the lack of data on other Arara groups, this feature only applies to the Ikpeng). The origin of the Arara group is probably northern Amazonia and their way of life is more oriented to the land than to the rivers, their agriculture is diversified, they have a refined technology and complex artwork (primordially weaving in cotton).

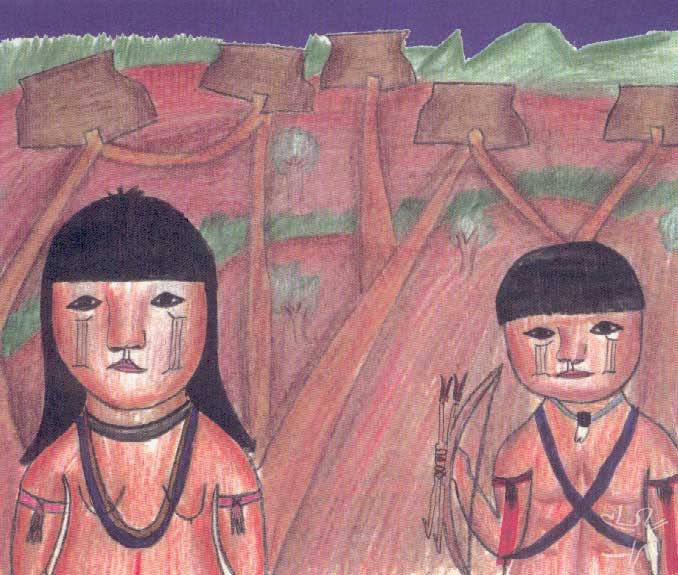

The term arara has been applied to Indigenous Amazonian groups from at least the beginning of the 20th Century, and the references to societies designated as Arara that inhabit the Lower and Middle Xingu are very numerous from 1850 on (Cf. Ehrenreich, 1895; Nimuendajú, 1931 and 1948). It is possible that the origin of the name (Arara = macaw) refers to the dark blue facial tattoo from the temples to the corner of the lips, the three parallel lines of which recall the bristly cutaneous folds of the black feathers around the macaw's eyes.

History of occupation

We have no knowledge of the existence of written records on the Ikpeng before their entry into the region of the feeder streams of the Xingu River. To reconstruct this itinerary, it is necessary to analyze the narratives (semi-mythical reports and oral traditions) of the Ikpeng themselves. These, however, only allow us to reconstruct an intermittent history with little time depth, of an imprecise zone in which personalities from specific present-day kin groups are not distinguished from great ancestors with supernatural powers of whom the myths speak.

Below, we will present a synthesis of the Ikpeng itinerary, which is told in greater detail in my work, In name of the others. Classification of social relations among the Txicão of the Upper Xingu (see the item Sources of Information).

In Ikpeng discourse, Kantavo is the original demiurge, about whom the stories refer to a time when these people had great enemies, but counted on the solid alliance of the Txipaya people. Their relations with the Txipaya were friendly and helpful, although the Ikpeng say that they took a group of them prisoner and brought them up, and that it was from this group that they learned the forms and ways of making baskets, the weaving of cotton, among other techniques. Besides that, they admit to having obtained various ritual songs and elements that were integrated to their rituals. Consistent with this, older sources (such as Nimuendaju, 1948 e Snethlage, 1910) indicate that Ikpeng were present among a Xipaya group which inhabited the banks of the Iriri, principal tributary of the Lower Xingu, leading us to believe that the Ikpeng would have inhabited that region.

By around 1850, the Ikpeng occupied an area characterized by many converging rivers, where they made war with a series of groups. But the names they give to the rivers do not allow us to identify the region. The general formation on the hydrographic basin, the description of certain natural resources (such as cashew nuts) and geographical features, as well as evidence from names and characteristics of their enemies, allow us to suppose that it was the Teles Pires-Juruena river basin, and more precisely the intermediary zone between the confluence of the Rio Verde-Teles Pires and the confluence of the Teles Pires-Juruena.

As for their enemies, they mention the Tapaugwo and the Abaga, the latter possibly corresponding to the Apiaká, which in this period (between 1850-1900) occupied an area between the Juruena and its tributary the Arinos. They also make reference to the Kumari, which does not correspond to the known designation of any people of this region, but perhaps refers to the Kaiabi. They also comment on the presence of a group of whites, who had horses and cattle, and from whom the Ikpeng captured one or several people. Curiously, the Ikpeng call the latter group Tupi. These permanent hostilities, although irregular, caused successive moves of Ikpeng villages.

A little before 1900, pressured by their adversaries, who, in turn, were pressured by the advance of the colonization frontier along the Teles Pires, the Ikpeng crossed the Formosa Mountains, an insignificant natural barrier that marks the division between the Teles Pires-Juruena and Alto Xingu basins. In this region, they seem to have been confronted once again by their enemies from the Teles Pires - Abaga and Kumari - besides a group that they called Pakairi, comprised of "whites and several blacks". Evidently this refers to the Bakairi of Paranatinga (a greater probability than those of the Rio Novo), who already were experiencing the consequences of contact with non-Indians, clothed as whites and raising cattle, mixed with caboclos -[descendants of Indians and whites]

The series of Ikpeng villages in the region of the upper Xingu - around 12 during the first half of the 20th Century - were all situated near the small tributaries or dead branches of the Jatobá or the Batovi, at approximately 13o latitude south. Around 1930, they began attacks against the more southern Xingu villages: wauja, nahukwá and mehinako. Thus, one may suppose that the history of Ikpeng territorial occupation corresponds to their inhabiting of the region of the Iriri at least until the first half of the 19th Century, followed by a migration to the upper Tapajós and, after several decades, their move to the upper Xingu, between the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

The pacification of the Ikpeng successfully completed by the Villas-Bôas brothers represents a definite rupture in the history of these people, which contributed to creating a new relation with the other ethnic groups of the region. Their fame as attackers and feared warriors changed drastically in 1960, when the Ikpeng captured two young Wauja girls. The girls were carriers of the "white man's" death, for the Ikpeng began dying from respiratory diseases caused by a flu virus. Besides that, the Wauja decided to seek revenge and got hold of firearms from a Brazilian. The conflict caused 12 deaths among the Ikpeng, but the Wauja were not able to get the girls back. Due to sickness and the "white man's diseases", the Ikpeng thus lost half their population within a few months.

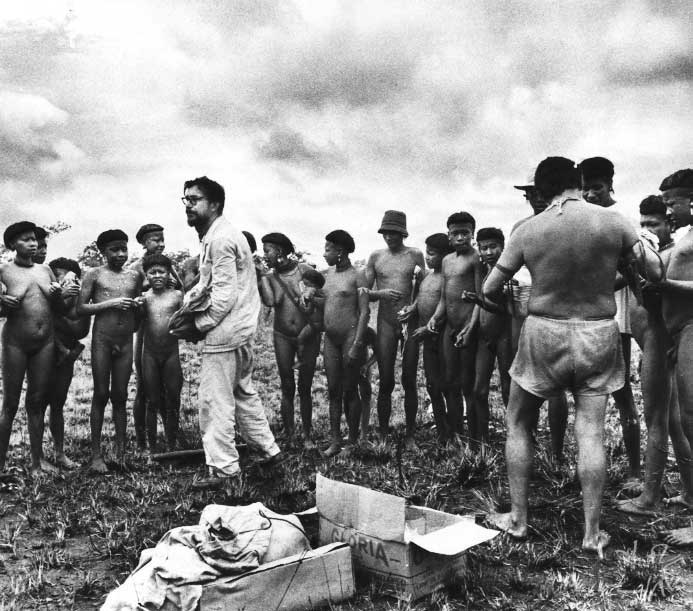

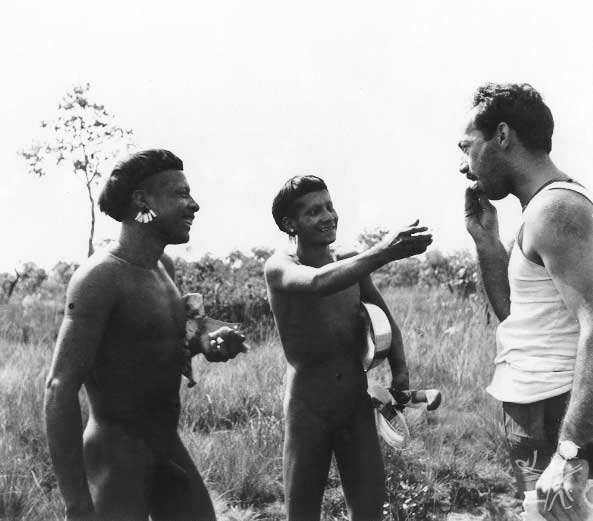

In 1964, the Villas-Bôas brothers found them to be in a very precarious situation, sick and malnourished. They then sought to assist them and provided them with metal tools. But the non-indigenous groups who invaded the region presented ever greater threats to their existence, bringing them new diseases, and, in 1967, the Ikpeng accepted transferral to another territory, within the boundaries of the Park.

Under the protection of the authrorities of the Xingu Indian Park, the Ikpeng began a new phase of dependence. From the health and nutritional point of view, they received daily support from the indigenous post. Besides that, the indigenists encouraged the other peoples of the Park to be generous with their old enemy. Thus, the Ikpeng dispersed for a short period, each familial group going to live in a different village. But their relations with their hosts were difficult, since the bad feelings resulting from the period of wars were still latent.

At the beginning of the 1970s, they regrouped and made a new village in the proximities of the Leonardo Villas Boas Indigenous Post, on the road that leads to the convergence of the Kuluene with the Tatuari rivers. They did not adapt well to the place and, between the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 80s, they moved to the region of the middle Xingu, below the village of Terra Preta, of the Trumai. In 1985, Megaron Txucarramãe, then administrator of the Park, created the Pavuru Indigenous Post, about 15 minutes distance from the Moyngo village. Today, this Post is administered by the Ikpeng, and is almost like another village, where families of FUNAI employees (the head of the post, assistants, boat pilot, etc.), and one of the teachers and Ikpeng employees of the health district live. There is even a family responsible for the Ronuro Vigilance Post, near the Ikpeng's traditional territory, on the Jatobá river. Generally speaking, the Ikpeng are very much involved in the defense of the territory of the Park, keeping watch and taking invaders, such as lumbermen and fishers, prisoner.

But the main objective of the Ikpeng lately has been to regain their territory prior to their transferral to the Park, in the region of the Jatobá River, contiguous with the Xingu Indian Park, but outside its borders. In September, 2002, Ikpeng made an expedition to this territory, for the purpose of reconnaissance and to bring back resources such as medicinal plants and shells to make earrings.

Population

When I first met the Ikpeng, a few weeks after their rescue by indigenists, their population was very sparse. The 56 individuals who arrived alive at the Leonardo Villas-Bôas post were quickly reduced to 50, because of an accidental death and five deaths from diseases. By the end of 1969, however, the births increased and when I returned there, in 1972, the Ikpeng had a total population of 62.

The population curve of the Ikpeng before the attack of the Wauja, which marked the beginning of their decline, was relatively stable, given that the confrontations with other groups did not result in many deaths and probably they hadn't yet been exposed to viral infections against which they had no immunity. Thus, from 1932 to 1952, according to a series of sources, the Ikpeng had an average population of 148 people.

If we investigate the facts regarding this brutal decline during the 1960s, when the population was reduced by more than half, we clearly perceive that mortality by disease was far greater than mortality by violence. But, in the following decades, there was an effective demographic recovery and today, the Ikpeng total 315 individuals.

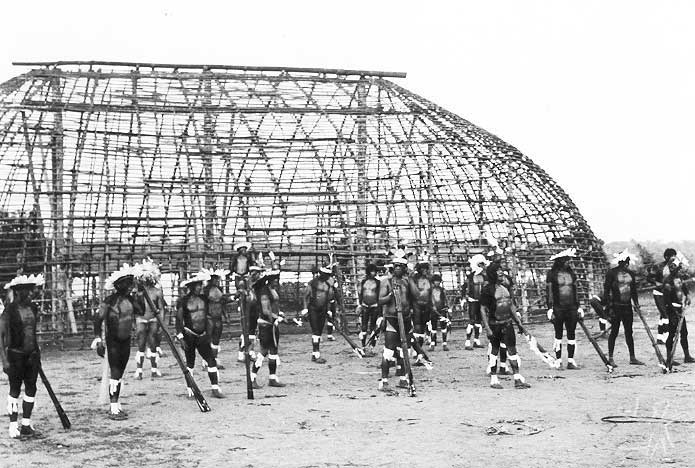

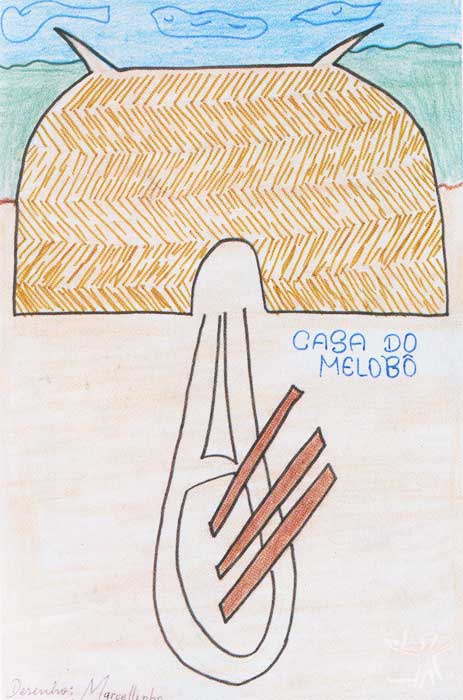

Village and cerimonial plaza

As stated in the previous section, the present Ikpeng village is located on the Middle Xingu, below the village of Terra Preta, of the Trumai. The model of the Ikpeng village contains the "moon" or ritual plaza, consisting of an ellipse with two fires, as a cerimonial center. In the ellipse there is a covered hut with a double sloping roof and no walls, called the mungnie, which is not a men's house, as in other Xingu societies, for the women generally have access to the place. It is rather at once, an atelier for artwork - with better illumination than the very dark dwelling-places -, a rehearsal room for cerimonial preparations, a place where friends can drink and eat outside the domestic context, and, finally, the "arsenal" where a few men, under strict tabu, make the headdress called otxilat, which represents the principal apparel of the warrior.

In general, the great Ikpeng rituals are held on the central plaza and mark life passages, most of the time involving the whole village. In the final phase of the initiation cycle (which culminates with the tattooing of the faces of boys from eight to ten years old), for example, the hunters return from having spent several weeks in the forest carrying pieces of smoked meat, which are brought in an immense basket, with the help of a front band and supplementary nets, that is placed on the plaza for the distribution of the meat.

The cerimonial paths are always elliptical, given that the dances are made around two points, one of which is the center of the house and the other the center of the mungnie. Even when the village consists of several houses and the mungnie is in the center (which is the case of the present village), each house forms with the mungnie a circuit for the elliptical dance.

The Moyngo festival

The principal festival celebrated by these people is male initiation, called Moyngo, in which the faces of the boys are tattooed. The ritual is preceded by many dance sessions and, at end, by a great hunt, organized by the fathers of the boys to be tattooed, who are the owners of the festival. After about a month, a messenger from the expedition is sent to the village announcing the return of the hunters. On the following day, during a session of dances to the sound of flutes and the song of the chief, the hunters arrive with an immense basket, full of game meat (especially monkeys). The hunters set up camp near the village and the women go there to fetch the smoked meat and to take manioc bread. The participants cover their bodies with a wood resin over which they stick bird feathers. At night they enter the village and drink sweet perereba fruit (porridge). After that, each man dances holding with one hand a child who will be tattooed and in the other a torch. They pass another entire night dancing. Finally, on the last morning of the festival, the children are tattooed. First incisions (stripes) are made on the face of the boys with a tucum thorn and then they apply carbon extracted from jatobá resin.

The Ikpeng have also adopted several festivals typical of the upper Xingu, such as the Tawarawanã and the Yamurikumã, which they perform annually. Moreover, many adornments typical of the Indians of the upper Xingu, such as snailshell collars or body paintings, have been incorporated (To learn more about the rituals and material culture of the upper Xingu, see the page on the Indigenous Park of the Xingu).

Social organization

Three major levels of Ikpeng social organization can be distinguished: the people, the house, and the hearth. Among the Ikpeng there is no single expression that designates exactly the "people", as a community of language and culture, but there are various forms that denote particular aspects of collective existence. In the presence of a non-Ikpeng, the exclusive "we", txmana, is used by preference, which is opposed to the set of foreigners or enemies, uros. As a term of reference, often the phrase "ompan Ikpeng ninkun", which means "all the Ikpeng" is used.

The Ikpeng social whole is a group that expresses moral solidarity in relation to outsiders, that speaks the same language (tximna muran) and is usually valued through the term tempano, "group of men", above all in solemn and cerimonial contexts, in which the essential humanity of "we" is opposed to the ambiguous humanity of the foreigner-enemy.

The second level which one can recognize in Ikpeng society is the domestic group. They live in a single dwelling - the architecture of which is similar to the upper Xingu type - comprised of domestic units of variable kinds and dimensions. The house does not privilege one type of social relation, but rather contains all the social ties existing among inhabitants of different houses, although with greater density. Thus, it is very common that the women of one house go together to gather manioc and prepare manioc bread. In the same way, co-resident men usually hunt and fish together.

Each one of the several nuclear families or co-resident domestic units are then grouped around a hearth, which serves for cooking and warming up the cold nights. Those who share this "fire" comprise the third recognizable level of Ikpeng society, generally comprised of husband, wife and shildren (biological and occasionally adoptive). As the Ikpeng practice polygyny and polyandry, both the man and the woman can have more than one spouse who also shares a space around the hearth.

Generally speaking, the Ikpeng do not differentiate consanguineal from affinal (kin by marital alliance) kin. Thus, kinship does not necessarily imply common ancestry, and can be treated in terms of future procreation. Thus, virtually all Ikpeng are kin, the differences occuring in the degrees of kinship relative to marital rules.

Among the Ikpeng, there is no notion of lineage, for a son is always a descendant of his father and a girl is always a descendant of her mother. Properly speaking, conception is the result of copulation, but the male fetus (tempano) is comprised solely of sperm substance. Thus, it is necessary to constantly nourish the growth of the embryo, and a woman's husband is not capable of fulfilling this task by himself. It is the regular lovers of the future mother and, occasionally, other men who those come to be considered as lovers, who help in this task. The role of the mother,however, is not merely one of a simple receptacle, for she is responsible for the form of the child, while the fathers are responsible for his substance.

The nuclear family, or more precisely the group comprised of mother, her children, her husband, and "associated genitors" forms a community of substance, in the heart of which there occur constant exchanges of body fluids which, when added up, could produce a neutral or balanced result, but the excesses of which cause corporal modifications that have dangerous, or even fatal, repercussions, on the spiritual being of the most fragile members of the community, the children.

Effectively, the rule of bilateral filiation and the set of other social rules do not define any social segment between the ethnic community and the restricted family. Economic and political factors, however, can shape the form of groupings and thus lend a certain plasticity to the collective arrangements.

The status of prestige (werem: "the master", or weblu: "the provider", or simply oke: "the great") depends on personal qualities and efforts and are not hereditary. There are always several werem, around whom a network of kin groups may crystallize for a certain period of time. Finally, each house has a "headman", who is responsible for coordinating daily activities, but who does not necessarily exercise the function of chief.

War and social reproduction

War is a central question in Ikpeng culture, present in the myths and the worldview of these people. The acquisition of goods has only secondary importance for warfare. Its main purpose is to avenge the dead, or even avenge death. For the Ikpeng, it is the witchcraft of the enemies that causes death, and prisoners of war are substitutes for the deceased.

Any death in principle could serve as pretext for a vengeance expedition, because death, for the Ikpeng, is never a natural phenomenon, which happens by accident or by chance. It always results form the direct or indirect action of the enemy-foreigner (uros). In war, the enemy's desire to kill manifests itself as a visible murderous violence; on other occasions, witchcraft is the means which the enemy uses to get the same results, principally by sending sicknesses. This enemy is not an abstract entity, but refers to people close to the village, generally neighboring groups. As the cases of homicide are very rare among the Ikpeng - and, when they occur, it is believed that the killer has been possessed by the spirits and did not know what he was doing -, voluntary evil only exists, and always exists, between enemies.

But the enemy, once captured, is incorporated into Ikpeng society, is treated well and is a source of prestige for the family who has adopted him. This family seeks to systematically ridicule his culture of origin and praise that of the Ikpeng, and, as a result, many captives have refused to go back to their group of origin, even when the circumstances permitted.

In this sense, social reproduction goes through two distinct and to a large degree opposed modalities: biological birth and sociological incorporation. Thus, one can be born Ikpeng (when the parents are), but one also can become Ikpeng by virtue of being captured or incorporated, for in that case, the person substitutes an Ikpeng who died. Despite the number of captives incorporated into Ikpeng society being very small, there is an intellectual and moral need for substituting the dead through prisoners.

Another element related to the status of the captive - who can receive an Ikpeng name or keep the name from his language, but who frequently assumes an ethnic nickname that recalls his origin- is that his worth is in part measured by his "naming" capacity. The captive, in effect, is a privileged namer given that he is able to recall foreign names, which is why part of the present-day Ikpeng population has Xinguan names.

Thus, the substitution of the dead takes place through births as much or more so than through captives, and both are incorporated into the totality through the system of names.

The importance of names

Most Ikpeng individuals have an impressive number of names (between six and fifteen, on the average a dozen). The chain of names that each one possesses is recited in a ritual (orengo eganoptovo: "recitation of names") related to the cerimony of returning from a successful war expedition. Or it is recited on very formal occasions during which a "great man" (who is not called "chief", for this term is inadequate) expresses the speech of the group, through special forms. In this case, he begins the discourse through the proclamation of names, and will repeat this several times, to emphasize what he is saying. Each chain of names is called orengo and is composed of a more common and important name, the emiru - which is acquired in an advanced stage of life, always after the death of one's parents -, and imon names- which are given after birth.

The process of naming is cumulative, given that during a person's lifetime he is usually named several times and retains all the names. The utilization of these names is opposed to nicknames which are affectionate epithets, mocking or occasional. The nickname is amut, a term that designates a type of decorative object used jokingly. In contrast with names, the nicknames are descriptive, specific to the individual, depending on the circumstances, and forgettable. Most Ikpeng possess one nickname, and these are the designations that are the most used in daily life, to the detriment of the names. That is, despite the fact everyone has many names, their daily use is rare. In any case, the process of naming is fundamental to the conception of the world and the social reproduction of these people.

The process of naming is done according to a chain of three members, within a kin group. One kin chooses a sequence of already existing names from one of his own kin, generally deceased. Then there is another person who names and someone who is named. The relation between the latter two is, often, one of close kinship, such as parents, uncles/aunts and grandparents.

The choice of the name is not arbitrary, but is determined by rules for the transmission of the names, and also, by considerations of the quality of social identity. Thus, giving a child the name of an ancestor who may have suffered from a grave shortcoming or a pernicious excess, is avoided, for there is the possibility that the destiny of this ancestor may be repeated in the child.

In this manner, through name transmission, the Ikpeng conceive of a continuous relation with the ancestors, which goes back to the mythic founding heroes. But it is not only social continuity that is guaranteed through name transmission, but also new names are incorporated over time, whether because certain nicknames are adopted as names and transmitted or, mainly, through the incorporation of names of foreign captives. Even though they may be few, the importance of captives as namers is great and, as soon as they have children with an Ikpeng, they are summoned by preference to give names.

In the Ikpeng logic of taking captives as a way of substituting a dead person, one can say then that, from the point of view of substance (beings of flesh), the system is conceived as a state of equilibrium (one dies, a foreigner is captured to substitute him); but from the point of view of quality, the foreign substance represents an addition, in the form of new names.

Even though the historic moment in which they are living has interrupted the warrior cycle and capture of foreigners, this model continues to operate on a conceptual level, concentrating on the symbolic plane a way of thinking and acting in the world.

The indigenous school

In recent years, the Ikpeng people have attributed great value to school education. There are four teachers among them and it is the village of the Park that has the greatest number of students (107). In 1994, with the help of linguists, the Ikpeng teachers elaborated a form of writing, in the context of the Teacher Training Program of the Xingu Indian Park (of the Socioenvironmental Institute). As a result, Ikpeng writing has been greatly used by the students, who also learn the Portuguese language, which is spoken with great fluency by most of the population. The Ikpeng school has assumed a central role in the Project, being responsible for the acquisition of school materials and its distribution to other villages of the Middle Xingu.

Sources of information

- CAMPETELA, Cilene. Análise do sistema de marcação de caso nas orações independentes da língua Ikpeng. Campinas : Unicamp, 1997. 160 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Aspectos prosódicos da língua Ikpeng. Campinas : Unicamp, 2002. 209 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

; PACHECO, Frantomé (Orgs.). Textos na língua Ikpeng. São Paulo : ISA, 1996. 101 p.

- EMMERICJ, Charlotte. A fonologia segmental da língua txikão. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1972. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- FERREIRA, Mariana Kawall Leal (Org.). Histórias do Xingu : coletânea de depoimentos dos índios Suyá, Kayabi, Juruna, Trumai, Txucarramãe e Txicão. São Paulo : USP-NHII ; Fapesp, 1994. 240 p.

- GALVÃO, Eduardo. Diários do Xingu (1947-1967). In: GONÇALVES, Marco Antônio Teixeira (Org.). Diários de campo de Eduardo Galvão : Tenetehara, Kaioa e índios do Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1996. p. 249-381.

; SIMÕES, M.F. Notícia sobre os índios Txikão -Alto Xingu. Boletim do MPEG: Série Antropologia, Belém : MPEG, n.s., n.24, 23 p., 1965.

- IKPENG, Korotowi; IKPENG, Iokore; IKPENG, Maiua. Ikpeng Orempanpot. São Paulo : ISA, 2001. 90 p.

- MENGET, Patrick. Au mon des autres : classification des relations sociales ches les Txicão du Haut Xingu (Brésil). Paris : Université Paris X, 1977. 306 p. (Tese de Terceiro Ciclo)

. Em nome dos outros : classificação das relações sociais entre os Txicão do Alto Xingu. Lisboa : Assírio & Alvim, 2001. 334 p.

. From forest to mouth : reflections on the Txicão theory of subsistence. In: KENSINGER, Kenneth M.; KRACKE, Waud H. (Eds.). Food taboos in lowland South America. s.l. : s.ed., 1981. p.1-17.

. Le propre du nom : remarques sur l'onomastique Txicão. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris : Société des Américanistes, v. 79, p. 21-31, 1993.

- PACHECO, Frantome Bezerra. Aspectos da gramática Ikpeng (Karib). Campinas : Unicamp, 1997. 145 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

. Morfossintaxe do verbo Ikpeng (Karib). Campinas : Unicamp, 2001. 303 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- RIBEIRO, Berta G. Diário do Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : Paz e Terra, 1979. 266 p.

- SIMÕES, Mário E. Os "Txikão" e outras tribos marginais do alto Xingu. Rev. do Museu Paulista, São Paulo : USP, v.14, p.76-105, 1963.

- VILLAS BÔAS, Cláudio; VILLAS BÔAS, Orlando. A marcha para o oeste : a epopéia da expedição Roncador-Xingu. São Paulo : Globo, 1994. 615 p.

- Marangmotxíngmo Mïrang : Das crianças Ikpeng para o mundo. Dir.: Natuyu Yuwipo Txicão; Karané Txicão; Kumaré Txicão. Vídeo Cor, NTSC, 35 min., 2001. Prod.: Vídeo nas Aldeias

- Moyngo. Dir.: Kumare Ikpeng; Karane Ikpeng. Vídeo Cor, 40 min., 2000. Prod.: CTI

VIDEOS