Nambikwara

- Self-denomination

- Anunsu

- Where they are How many

- MT, RO 2332 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Nambikwára

Famous in the history of Brazilian ethnology for having been contacted ‘officially’ by Field Marshall Rondon and studied by the renowned anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the Nambikwara today live in small villages on the headwaters of the Juruena, Guaporé and (previously) Madeira rivers.

They inhabit both the cerrado and the Amazonian rainforest, as well as the transitional areas between these two ecosystems. The Nambikwara occupied an extensive region in the past and showed a pronounced spatial mobility. Possessing an apparently simple material culture and an extremely complex cosmology and cultural universe, the Nambikwara have preserved their identity through a mixture of aloofness and opening to the world.

Names

The term Nambikwara is Tupi in origin and can be glossed as ‘pierced ear.' It was following the Rondon Commission’s expedition into the interior of Mato Grosso that the Indians until then referred to as ‘Cabixi’ became called the ‘Nambikwara,’ the name by which they are still known today.

The Pareci guides who worked for the Rondon Commission thought that this Tupi tern – used originally to designate a group speaking a Gê language located in the region between the Arinos and Sangue rivers – meant ‘enemy’ and thus used it when they spoke in Portuguese with the Commission’s members to refer to their western neighbours.

Other spellings

The ethnonym may be found written in other forms: Nambikwara, Nambicuara and Nhambicuara.

Hence since the start of the 20th century, this term has been used to designate the various groups who occupy the region spanning the northwest of the state of Mato Grosso and the border areas of the state of Rondônia, between the affluents of the Juruena and Guaporé to the headwaters of the Ji-Paraná and Roosevelt rivers.

Other names

While the name ‘Nambikwara’ is a generic designation for the peoples inhabiting the Chapada dos Parecis, the Guaporé valley and the region more to the north, there are on the other hand a profusion of names used by the Indians to designate the Nambikwara subgroups.

Among the Northern Nambikwara, there are the Da’wandê, the Da’wendê, the Âlapmintê, the Yâlãkuntê (Latundê), the Yalakalorê, the Mamaindê and the Negarotê. Among the Southern Nambikwara, ther are the Halotésu, the Kithaulhu, the Sawentésu, the Wakalitesu and the Alakatesu. And among the Nambikwara of the Guaporé valley, we find the Wasusu, the Sararé, the Alãntesu, the Waikisu and the Hahãitesu.

Language

The groups that occupied and still occupy the Chapada dos Parecis, the Guaporé valley and the northern region, between the Iquê river and the Cabixi and Piolho rivers, speak languages from the Nambikwara linguistic family. No relationship has been discovered between this family and any other South American linguistic family.

According to David Price’s classification (1972), the Nambikwara linguistic family can be divided into three major groups of languages spoken in different regions of the Nambikwara territory. These are: Sabanê, Northern Nambikwara and Southern Nambikwara.

“With the exception of the Sabanê language, which today has less than 20 speakers, the other Nambikwara languages are well preserved. Portuguese is spoken by all Southern Nambikwara and by most of the Northern Nambikwara. In the Guaporé valley, understanding of Portuguese is more accentuated among the younger generation. In general, women also have less knowledge of Portuguese than men, as the latter leave the villages much more. The only area that developed multilinguism among the Nambikwara is the north. In the 1990s, there were still speakers of Sabanê and the Northern Nambikwara who could speak the three Nambikwara languages (plus Portuguese). Multilingualism in this case was the result of the intensification of the contact between these groups.” (Marcelo Fiorini).

Sabanê

The Sabanê language, spoken by groups inhabiting the extreme north of the Nambikwara territory, probably to the north of the river Iquê in the region between the Tenente Marques and Juruena rivers, presents major differences in relation to the other two languages.

In a comparative study, Price (1985) concluded, based on the high number of cognates [similar words] observed among the Sabanê and the other two Nambikwara languages, that, despite the differences, the Sabanê language belongs to the Nambikwara linguistic family. The Sabanê-speaking groups were severely affected by the epidemics provoked by contact and many of them became extinct.

Currently, most of the survivors from these groups are located in the Pyreneus de Souza Indigenous Territory and are generically classified as Sabanê. Some of them live with the Mamaindê and some families have migrated to the city of Vilhena in Rondônia.

Northern Nambikwara

The groups speaking the Northern Nambikwara language inhabit the valleys of the Roosevelt and Tenente Marques rivers, as well as the region further to the northwest, which includes the area drained by the Cabixi and Piolho rivers. They are designated: Da’wandê, Da’wendê, Âlapmintê, Yâlãkuntê (Latundê), Yalakalorê, Mamaindê and Negarotê.

Price (1972) states that all the dialects of this language are mutually intelligible, despite the small variations observed between the dialects spoken in the region of the Tenente Marques and Roosevelt rivers and those spoken in the region of the Cabixi river, traditionally inhabited by the Mamaindê. The author suggested that the dialect spoken by the Negarotê, a group located on the shores of the Piolho river, was an intermediary dialect between the other two. Recent studies undertaken by linguists from SIL indicate that the dialect spoken by the Negarotê is very similar to that spoken by the Mamaindê.

Southern Nambikwara

The language classified as Southern Nambikwara is spoken in the rest of the Nambikwara territory, which can be divided into three dialect areas: the Juruena valley, the region formed by the Galera and Guaporé rivers and the Sararé valley.

In the Juruena valley region are found the groups referred to in the bibliography as the 'Cerrado Nambikwara’ or ‘Savannah Nambikwara.’ These groups are located in the northeast of the Chapada dos Parecis and are designated: Halotésu, Kithaulhu, Sawentésu, Wakalitesu and Alakatesu.

Price (1972) distinguished four dialects spoken by the groups inhabiting the Chapada dos Parecis as a whole. The first is spoken by the groups situated to the far north of the plateau, in the region known as Serra do Norte. These groups were known as Niyahlósú, Si’waisu and Lunkatesu, and are currently known as Manduca. The second dialect is spoken by the groups located in the region drained by the Camararé river, the third by the groups living in the region between the Formiga and Juína rivers, and the fourth by the groups situated in the area between the Juruena and Sapezal rivers.

Despite speaking the same language (Southern Nambikwara), the groups located in these four dialect areas find it difficult to understand each other, with the groups located in the Guaporé valley seeming to speak an intermediary dialect between those spoken in the Juruena valley to the east and the Sararé valley to the southwest of the Nambikwara territory.

The groups inhabiting the region formed by the Guaporé valley below the Piolho river are known as: Wasusu, Sararé, Alãntesu, Waikisu, Hahãitesu and are generically called ‘Wãnairisu,’ a term that refers to a type of haircut typical to the groups of this region (Fiorini 1997: 1).

Location

The territory traditionally occupied by the Nambikwara can be divided into three geographic areas.

The first is formed by the Chapada dos Parecis, corresponding to the eastern part of the Nambikwara territory. This region consists of a plateau cut by the Juruena river and its affluents: the Juína, Formiga, Camararé, Camararézinho, Nambikwara, Doze de Outubro and Iquê rivers. The area is covered by large tracts of savannah. Dense forest covers just 5% of the region. The groups who live in this area conceive the entire territory occupied by the Nambikwara in terms of the distinction between savannah (halósú) and forest (sá’wentsú).

The Guaporé valley region corresponds to the west of the Nambikwara territory between the border of the Chapada dos Parecis and the Guaporé river. Eighty-five percent of the region is covered by forest. In the part below the plateau, the forest is denser and the soil more fertile. The forest thins out towards the west, towards the Guaporé river, an area which is composed of lowland fields and floodplains. Flowing towards the Guaporé river are the Cabixi, Piolho, Galera and Sararé rivers. The latter defines the southern limit of the territory occupied by the Nambikwara. The region of the Sararé river is separated from the remainder of the Guaporé valley by the Chapada São Francisco Xavier. The Guaporé river flows into the Madeira river to the northwest.

In the north of the Nambikwara area, forests cover the region along the Roosevelt and Ji-Paraná rivers, as well as their affluents. In all three regions, the climate is split between a rainy season between September and March and a dry season from April to August.

The Nambikwara usually locate their settlements close to the headwaters of rivers and, as Price observed (1972), the actual limits of the Nambikwara territory tend to be related to the limits of navigability of the rivers traversing it. Price therefore suggests that the extensive area occupied by these groups may have been defined by the natural obstacles that prevented the incursion of riverside-dwelling Indians who used canoes, such as the Tupi groups.

Population data

David Price’s estimate for the Nambikwara population at the start of the 20th century was around 5,000 people. Lévi-Strauss, on the other hand, calculated that at this time the Nambikwara totalled 10,000 Indians, while in 1938, the date when he stayed with some of the Nambikwara bands, he estimated the population at between 2,000 and 3,000 people.

The census conducted by Price in 1969 showed that 30 years after Lévi-Strauss’s expedition through the Nambikwara territory, these groups had been reduced to 550 individuals.

In the last two decades a population growth has been observable among the region’s groups. According to the census recorded by ISA in 1999, the Nambikwara population numbered 1,145 people. In the last census, carried out by FUNAI in 2002, the Nambikwara totalled around 1,331 people.

Despite the recent demographic growth, many groups have become extinct and others reduced to a few individuals. This was the case of a portion of the Northern Nambikwara groups, whose survivors joined with other, more numerous groups to form a single group. Currently, some survivors from the Da’wendê, D’awandê and Sabanê groups, for example, live with the Mamaindê at the Capitão Pedro Indigenous Post.

Contact history

First Records

David Price undertook extensive historical research on the occupation of the region traditionally inhabited by the Nambikwara. According to him, the intensive occupation of what today corresponds to the state of Mato Grosso began with the discovery of gold in the Coxipó river in 1719, luring the Portuguese to the region. In 1737 gold was discovered in the Chapada São Francisco Xavier, in the far south of Nambikwara territory. However, there are no records of any encounter with Indians during this period.

The first records of the region occupied by the Nambikwara date from 1770, when an expedition was organized to build a road linking Forte Bragança to Vila Bela and to search for gold in this region. The documents relating to this expedition mention the presence of Indians, including the ‘Cabixi,’ located between the upper course of the Cabixi river, the Iquê river and the lower course of the Juruena. More than likely, the people were the Sabanê, a group that inhabited the far north of the Nambikwara territory.

During this period, as well as the term ‘Cabixi,’ various other terms were used to designate the groups known today as Nambikwara. A subgroup of the Pareci was also known as Cabixi during the same period and, in come historical records, a distinction was made between the ‘tame’ and ‘wild’ Cabixi, referring to the Pareci and the Nambikwara, respectively.

In 1781, the first attempt was made to settle the Indians known as Cabixi who lived in the region of the Sararé valley. Documents from the period mention the presence of 56 Indians classified as Pareci and Cabixi. However, this small mission village was abandoned in 1783.

The existence of quilombos in the Cabixi territory, close to the Piolho river, is also mentioned. This region is currently occupied by the Nambikwara group known as Negarotê. The population of quilombos was constituted by former black slaves who had fled from the gold mines in the Chapada São Francisco Xavier, and by Indians and caborés (people of mixed black and Indian ancestry). Various documents report the dispatch of expeditions to capture and punish the runaway slaves and destroy the region’s quilombos. One well-documented expedition was sent in 1795 by the then Governor General of Mato Grosso, João Albuquerque Pereira de Mello e Cárceres. This expedition left the town of Vila Bela, journeyed down the Guaporé river and up the Cabixi and Pardo rivers (an area traditionally inhabited by the Mamaindê) before continuing overland to the Piolho river, where blacks and Indians were captured and taken back to Vila Bela.

Price (1972) records an account given by a old Kithaulhu man who states that his warred with a people with curly hair who lived in the forest. This informant also told him of the sites where shards of pottery produced by this people could be found, attesting to the existence of quilombos in the region.

By the end of the 18th century, the mines of the Chapada São Francisco Xavier were becoming exhausted and many of the towns that had sprang up in the region were abandoned. There are records from this period of attacks launched by the Cabixi on the region’s towns and settlements. Indians called by this name threatened the workers involved in poaia extraction, an activity that began in the region in 1854.

The attacks by the Indians on the population of Vila Bela lasted until the beginning of the 20th century when the expedition led by Rondon entered the territory occupied by the Nambikwara.

Rondon Commission

In 1907, the Rondon Commission initiated the first expedition to the region of the Juruena valley to determine the trajectory of the telegraph line that would link Mato Grosso to Amazonas.

When the Rondon Commission entered the Nambikwara territory, these Indians were already in contact with rubber tappers with whom they frequently warred. During this period, the Nambikwara already used metal axe acquired from the rubber tappers. The attacks launched by the Nambikwara against the employees of the telegraph stations probably resulted from the association made by the Indians between these workers and the rubber tappers who typically killed the men and kidnapped the women.

Although the Nambikwara had already had sporadic contacts with the rubber tappers and the former slaves who lived in the region’s quilombos, it was from the beginning of the 20th century onwards with the creation of the SPI (Indian Protection Service), directed by Rondon, that the first peaceful contacts were established with the Nambikwara Indians.

The arrival of the missionaries

The telegraph lines also cleared the way for the entry of missionaries into Nambikwara territory. Price (1972) relates that in 1924 a missionary couple from the Inland South American Missionary Union, a Protestant organization based in the United States, settled close to the Juruena Telegraph Station.

A short while before their arrival, six telegraph line workers had been killed by the Nambikwara, possibly in revenge for the death of an Indian who had been hit by a shotgun fired by the Station’s inspector. The couple left the Station in 1927 and returned with a small child in 1929, when they were attacked by the Wakalitesú after they had medicated an Indian who subsequently died. Only the women survived the attack. She returned to the United States where she devoted herself to raising funds to ensure the mission continued.

In 1936, the same missionary organization was re-established at the Campos Novos Telegraph Station where it remained until 1948. In 1957, a Station occupied by missionaries was built on the Pardo river, which was transferred to the Camararé village in the Juruena valley in 1961.

In 1950, the Guaporé valley also saw the arrival of missionaries, this time from an organization known as the New Tribes Mission, who were killed, though, by the Nambikwara shortly after arriving in the region.

In 1959 and 1960, missionaries from the Missão Cristã Brasileira began to make contact with the Nambikwara of the Sararé valley. During this same period, missionaries from another organization, called the Wycliffe Bible Translators, or the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), began to work with the Nambikwara groups. Menno Kroeker and Ivan Lowe settled in the Serra Azul village, beginning their studies of the Southern Nambikwara language. David Meech and Peter Weisenberger, in 1962, began to work with the Mamaindê and were succeeded by Clifford Barnard and later by Peter Kingston who initiated studies with the Mamaindê language (Northern Nambikwara). These were the first systematic studies of the Nambikwara languages.

Since 1930, Catholic missionaries had already been working with the Nambikwara of the Juruena valley at the Utiariti Mission, where they ran a school for teaching literacy and catechizing the region’s Indians (Pareci, Nambikwara, Iranxe/Manoki).

Mentioning the presence of missionaries among the Nambikwara groups, Price (1972) makes the following claim: “despite the heavy evangelization, I have never met a Christian Nambikwara.”

The permanent contacts of the Mamaindê were not with Catholic missionaries, but with the Protestant missionaries of SIL who were present in the village from the 1960s onwards, albeit more sporadically from the 1990s onwards. However I never heard a Mamaindê person define themselves as a ‘believer.’ They know the bible and part of it has been translated into the Mamaindê language by the missionaries. In some situations, especially when responding to my questions on the forest spirits, they used the term ‘Satan’ to designate the latter.

Some young people are encouraged by the missionaries to leave the village to study in the school by the mission in the Chapada dos Guimarães, close to Cuiabá (MT). There they are taught to read and write in Portuguese and undertake courses to become pastors and hold religious services in their own villages. However, at least during the period when I was living with the Mamaindê, I never saw any of these young people hold services or speak of the bible in the village. When telling me about their experiences at the school, they emphasized what they had learned about white people’s way of life.

The era of the Indian Protection Service

In 1919, an Indigenous Post was created at Pontes de Lacerda (MT) to attract and pacify the Nambikwara of the Sararé valley. This Post was transferred in 1921 to a site close to the Sararé river, but was never able to make contact with the Nambikwara of this region.

In 1925, an Indian Protection Service (SPI) Post was established on the Urutau stream, close to the Juina river, which attracted many Indians. Following a reduction in the federal funds allocated to the SPI, the Post was gradually abandoned. In 1942, this Post was transferred to the Espirro stream on the headwaters of the Doze de Outubro river, close to the town of Vilhena. The officer Afonso França was named the head of this Post, which changed name to the Pyreneus de Souza Post.

França produced numerous reports on its activities and in these complained about the difficulty in keeping the Nambikwara living at the settlements for any length of time. According to him, the Indians stayed at the Post only long enough to acquire the goods they wanted and then returned to their own villages.

In the 1940s with the onset of the Second World War, rubber extraction intensified across the Amazonian region and during this period the Pyreneus de Souza Post began to sell rubber extracted by an indigenous workforce. I obtained accounts that, during this period, the Sabanê living at the Post were subjected to forced labour. Available reports suggest that rubber extraction had less impact on the region of the Guaporé valley below the Piolho river.

During the period spanning from 1940 to 1970 there are records of various epidemics striking the Nambikwara groups. The mortality rate in the villages that had no contact with the SPI Posts cannot be estimated. The groups known as Wakalitesú and Alakatesú, situated in the Juruena valley, were the most affected by the epidemics arising from contact, since their villages were located on the route of the telegraph line. On the other hand, the groups occupying the southwest of the Nambikwara territory, in the Guaporé valley, do not seem to have been so heavily affected by the epidemics during this period, since they avoided frequent contacts with the whites, preferring to remain in more remote locations.

In the 1950s, the federal government encouraged farming initiatives in the area inhabited by the Nambikwara as part of a regional development project. In 1956, Gleba Continental occupied the territory between the Camararé and Juína rivers, but the initiative proved unsuccessful and the region was abandoned in 1962. During this period, work began on constructing the highway linking Cuiabá (MT) to Porto Velho (RO) (today designated the BR 364), cutting the Nambikwara territory in half.

The era of Funai

In October 1968, President Costa e Silva created the Nambikwara Reserve in the region delimited by the Juína and Camararé rivers. The demarcated region, traditionally inhabited by just 1/6th of the Nambikwara groups, was composed almost entirely of an extremely poor and arid soil. The aim of the federal government’s project was to transfer all the Nambikwara groups to this single reserve, freeing the rest of the region for farming initiatives.

Soon after the demarcation of the Nambikwara Reserve, the recently created Funai began to issue Negative Certificates, testifying that there were no Indians in the area of the Guaporé valley. According to Costa (2002), a report from the Department of Lands, Mines and Colonization shows that in 1955 the lands of Mato Grosso were divided among 22 companies, each of them receiving a minimum of 200,000 hectares.

At the end of the 1960s, the lands of the Guaporé valley, the region with the most fertile soil within the entire Nambikwara territory, was being sold to farming companies receiving federal funds from SUDAN (Amazonia Development Agency).

In 1973, in an attempt to minimize the conflicts between the farmers and the Nambikwara, a strip of land between the Camararé and Doze de Outubro rivers was added to the Nambikwara Reserve. However, a short time later part of these lands were reoccupied by farmers.

The groups most affected by the occupation of the farming companies were those of the Guaporé valley whose lands had not been demarcated. These populations were subject to numerous attempts by FUNAI to transfer them to the Nambikwara Indigenous Reserve and, later, to an area in the south of the Guaporé valley. All these attempts were frustrated and the groups ended up returning to their original territory, which, however, was already occupied by farmers who deforested a large part of the forest, clearing it for pasture.

Funai therefore adopted another strategy and hired employees to demarcate small ‘islands’ of Indigenous Reserves and fix the different local groups who occupied the Guaporé valley regions within them. In 1979, four of these small Reserves were created, though in the case of two of them the original size was reduced following pressure from local farmers. Some groups, however, did not have even small parts of their territory demarcated.

Later between 1980s and 90s small areas of significant value for the Nambikwara were demarcated: the Lagoa dos Brincos Indigenous Territory (IT), where the Mamaindê and the Negarotê collected the shells needed to make the ear pendants used by them; the Pequizal IT, created with the aim of protecting the pequi fruit trees growing there, the basis of the Alantesu diet (the group's ethnonym in fact translating as ‘people of the pequi’); and Taihãntesu IT, a site where the Wasusu locate the ‘sacred caverns,’ the dwelling-place of the souls of the dead.

In the 1980s, World Bank funds were used to finance the Polonoroeste Project for building a road between the municipality of Pontes de Lacerda and the federal highway (BR 364) linking Cuiabá to Porto Velho. The road cut through the Guaporé valley, passing through the middle of the region inhabited by four Nambikwara groups whose lands had yet to be demarcated and close to the small areas demarcated for another three groups.

With the road open, immigrants from various parts of Brazil entered the region, setting up farms. During this period, logging also began in the Nambikwara territory. The Sararé valley was once again occupied by mineral prospectors. In 1992, the number of prospectors in the Sararé IT reached 8,000 (Costa 2002).

Today the extensive territory traditionally occupied by around 30 Nambikwara groups, some of them already extinct, is divided into nine non-contiguous Indigenous Territories: Vale do Guaporé, Pirineus de Souza, Nambikwara, Lagoa dos Brincos, Taihãntesu, Pequizal, Sararé, Tirecatinga and Tubarão-Latundê. The latter is located in the state of Rondônia and inhabited by Aikanã Indians and by a Nambikwara group denominated Latundê.

Groups and membership criteria

According to Lévi-Strauss (1948), the criteria that define a person as a member of a particular group are malleable and, sometimes, correspond to political interests, making it impossible to define the group to which a person belongs with any precision.

Writing on this topic, Price (1972) claimed that in most cases place of birth is used to define group belonging , while patrilinearity can also be invoked, though a wide margin for individual manoeuvring always exists. Price suggests that although the Nambikwara groups do not recognize themselves as political units, group belonging can be defined by use of the term anusu (‘people,’ in the Southern Nambikwara language).

Comparing the data of Price and Fiorini (1997) on the Southern Nambikwara groups with my own data on the Mamaindê (Northern Nambikwara), I noticed a variation in the use of this term. The groups of the south of the Guaporé valley, studied by Fiorini, classify only members of the same local group as anusu. The cerrado groups studied by Price, on the other hand, also considered members of related groups as anusu (i.e. all those connected by marriage alliances).

The Mamaindê use the term nagayandu (‘people’) to classify all members of the local group, but when used in opposition to ‘whites’ (kayaugidu), the term may also include all the Nambikwara groups and, in certain contexts, other indigenous groups living in the region, such as the Pareci and the Cinta-Larga. In addition, some animals may be called ‘people’ (nagayandu). Generally these kind of claims refer to the mythic past, when the animals were people, or to the fact that the spirits of the dead transformed into animals.

The extension of the use of the terms translated as ‘people’ therefore indicates that the limits of humanity depend more on the context than a prior or intrinsic meaning to the term. The same can be said of the ethnonyms attributed to the Nambikwara groups; far from indicating a previously defined group identity, these terms indicate the impossibility of defining the group itself without resorting to the viewpoint of others. We could therefore say that, in this ethnographic context, the limits of humanity and social groups depend fundamentally on a relationship.

Habitations, villages and swiddens

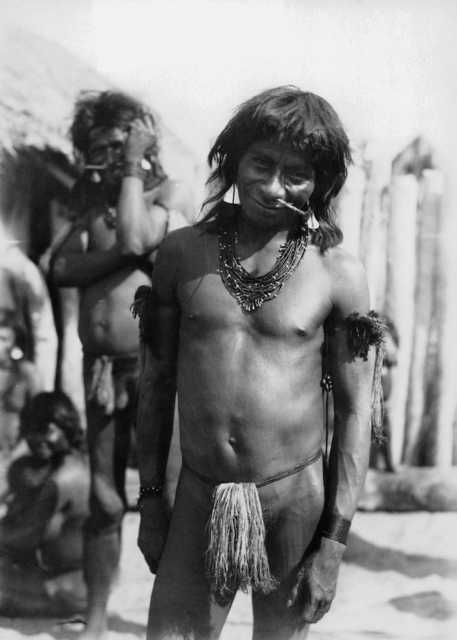

Different types of habitations were found in the villages located in each of the three reasons making up the Nambikwara territory. Among the groups of the north, the houses were conical; in the Guaporé region, the houses were large and elongated, while in the Juruena valley region they were smaller and semi-spherical.

Rondon (1922) described the first Nambikwara village that he visited, in 1907, in the Juruena valley. According to him, the village comprised one large house and another two smaller houses, both of which were semi-spherical and straw thatched. In one of the small houses he found bamboo flutes similar to those of the Pareci. According to his description, the village was circle in format with the area in front of the houses 'impeccably clean'.

Roquette-Pinto visited the Nambikwara of the Serra do Norte, the highest region in the north of the Chapada dos Parecis, in 1912. According to him, “the villages of the Indians of the Serra do Norte are generally built at the top of small hills, far from the rivers. Some are located more than a kilometre from the nearest river or stream. (...) The village is constructed in a large plaza some fifty metres in diameter; the ground is cleared of undergrowth, weeded by hand, and kept clear by the passing of the residents (...) The circular shape formed by the village in the middle of the cerrado assumes the a star form thanks to the trails radiating out from its circumference” (1975). He adds that the Nambikwara villages typically have two houses, one in front of the other, separated by a central plaza, and are generally located in the cerrado on more elevated sites.

Although they live in a forest region, the Mamaindê build their villages in higher areas with sandy soil and vegetation typical of the cerrado. The term halodu (field, cerrado or open space), used by the Mamaindê to designate the village, indicates that the savannah or cerrado is considered the appropriate place for locating a village.

Currently the Mamaindê inhabit a village situated on the high point of a plateau designated yu’kotndu (‘suspended on the edge/mouth’ [of the mountains]). The swiddens are cultivated in the lower part of the mountains in an area of dense forest between the Pardo and Cabixi rivers where the soil is more fertile.

Ideally the swiddens are cleared close to the village. However, swiddens may frequently be located two or three hours walk from the village. In this case, the family responsible for it usually build temporary shelters where they stay for the planting period and later during harvesting, thereby avoiding having to return to the village every day.

The village’s central plaza provides the location for the flute house, used to store these bamboo instruments and hide them from women, who are prohibited from seeing them. Today the Mamaindê and Negarotê villages no longer possess a flute house. The Mamaindê say that ceased storing the flutes in the village after contact with the whites intensified. They add that the flutes are now made and kept in the forest, far out of women’s sight.

According to David Price, the village plaza is the centre of public life, where the rituals are performed and where the dead are buried. The main criterion enabling a location to be defined as a 'village' is the fact that dead people are buried there. Hence the sites of many former villages tend to be remembered by the Nambikwara as locations where their ancestors reside. As a result, it can be said that the Nambikwara villages are primarily villages of the dead.

The Mamaindê recount that they used to spend much of their time in swidden camps. These locations could also be considered villages if dead people had been buried in them. When someone died far from the village and taking the body to be buried close to the house of their kin was impossible, a swidden camp was chosen or a site where a new swidden could be cleared. Consequently the place where the dead were buried could become a habitational site in the future.

Generally speaking, the villages are the places where the Nambikwara groups spend most of the year. Village sites usually changed every 10 to 12 years. During the planting and harvesting seasons, the families might relocate to the swidden camps, changing the residential makeup of the village, but after these periods they returned to the same site.

During hunt expeditions or on trips to visit distant kin, the Nambikwara also used to reside in temporary dwellings. Lévi-Strauss stayed with the Nambikwara in temporary encampments along the telegraph line built by the Rondon Commission and asserted that the Nambikwara were semi-nomads who spent most of their time travelling, concentrating in larger villages only during the rainy season. Subsequently, both Paul Aspelin and David Price questioned the classification of the Nambikwara as semi-nomadic, pointing to the importance of agricultural activity and the sedentary life in the villages, which provoked a debate on the mobility patterns of the Nambikwara (see Aspelin 1976, 1978; Price 1978; Lévi-Strauss 1976, 1978).

Female puberty ritual

As soon as she menstruates for the first time, the pubescent girl (wa’yontãdu, ‘menstruated girl’) must remain in reclusion in a house built by her parents especially for this purpose.

The Mamaindê refer to this small maloca made from burity leaves as wa’yontã’ã sihdu (‘menstruated girl’s house’). There the girl must remain for one to three months. At the end of this period, a large festival is held during which the guests from other Nambikwara villages remove her from reclusion. The girl (wekwaindu, ‘girl,’ ‘young woman’) is then considered a ‘formed’ woman, as the Mamaindê put it.

The female puberty ritual is performed by almost all the Nambikwara groups, apart from those occupying the southern Guaporé valley. Though the latter do not hold this type of ritual, they are similar to the cerrado groups in many other aspects.

Among the cerrado groups, the ritual presents some small variations. The Nambikwara themselves emphasize these differences, criticizing the other groups and accusing them of not knowing how to perform the ritual correctly. However, all the other Nambikwara groups who are called to take part in the initiation rituals of the others recognize these rituals as the same, despite the variations between them.

The Northern Nambikwara groups, including the Mamaindê, also perform the female puberty ritual and therefore form part of a wider network of relations that, as we have seen, involves the cerrado groups. According to a young Kithaulhu man (a cerrado group) married to a Mamaindê woman, the Mamaindê were the first to hold this kind of ritual and later taught it to the other Nambikwara groups.

According to Price, the groups located in the region drained by the affluents of the Juruena river state that very long ago the female puberty ritual was unknown and that the Negarotê – a Northern Nambikwara group neighbouring the Mamaindê – were the first to perform it. This was how the cerrado groups learned to practice it. For this reason, the set of music sung during the ritual is called nekato’téyausú, ‘music of the Negarotê,’ by these groups.

The Mamaindê possess a repertoire of vocal music called ‘menstruated girl music,’ which is associated with the female puberty ritual, but is not restricted to this context, since the music may be sung simply for fun. As well as vocal music, they also have a repertoire of ‘flute music’ and are the only Nambikwara group to use wind instruments made especially for the occasion.

Many authors who have studied the Nambikwara have recorded the practice of this ritual. Despite the contradictions and variations observable in the data, the descriptions of the female puberty ritual generally emphasize the change in the girl’s social status as she becomes a ‘marriable’ women on its conclusion.

Shamanism (Mamaindê)

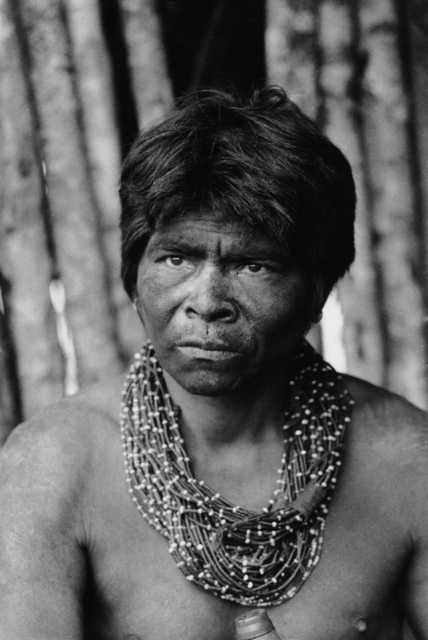

Shamanic power is described by the Mamaindê (a Northern Nambikwara group) as the possession of many objects and body decorations given to the shaman by the spirits of the dead and by the shaman who first initiated him in the techniques of shamanry. Consequently, the shamans possess the largest number of body decorations of anyone.

The two shamans active in the Mamaindê village continually wear numerous bands of black beads. One of them also constantly uses a strip of woven cotton round his head, sometimes replaced by a single line of red cotton, as well as cotton bands on his arms.

The shaman’s decorations and objects may be called wanin wasainã’ã, ‘magical things,’ or waninso’gã na wasainã’ã, ‘the shaman’s things.’ By possessing the decorations and objects of the dead, the shaman comes to perceive the world as they do, thereby acquiring the capacity to see the things that are invisible to most people.

Nonetheless, not only shamans possess body ornaments. The Mamaindê say that as well as the visible decorations, everyone possesses internal decorations that only the shaman can see and render visible during curing sessions. What makes a decoration visible or invisible is not any intrinsic characteristic attributed to it, but the observer’s visual capacity. From the point of view of the shaman, a being capable of adopting multiple points of view, the body of the Mamaindê always appears as a decorated body.

Although some objects and decorations are possessed solely by the shaman, what differentiates him from other people is the fact that he acquires these decorations directly from the spirits of the dead and thereby becomes capable of seeing them. In this sense, the term ‘magical things’ designates not so much an intrinsic quality of the shaman’s ‘things’ as the relations that he establishes with the spirits of the dead that lead to his possession of these ‘things."

Shamanic initiation

The Mamaindê describe shamanic initiation as a kind of death. Walking alone in the forest, the future shaman is beaten with a war club by the spirits of the dead and faints. Some people say that the spirits of the dead may also shoot arrows at him. At this moment he receives various ‘magical’ decorations and objects from the spirits. As well as the objects, the future shaman also receives a spirit-woman who is described as a jaguar, though the shaman sees her as a person. She will accompany him wherever he goes, sitting constantly by his side and helping him during curing sessions. The shaman may refer generically to the objects received from the dead and to his spirit-wife as da wasaina’ã, ‘my things.’ Both are responsible for his shamanic power.

The initiation of a Halotésu shaman (Savannah Nambikwara) was summarized by Price as follows: a man sets off into the forest to hunt and sees the animals as people. Later he encounters the spirit of an ancestor who calls him ‘brother-in-law’ and gives him a spirit-woman in marriage, singing her name for him to hear. The man takes her home and only he is able to see her. This woman is responsible for his shamanic power and becomes his assistant, always sitting by his side. She must be treated well or she will cause harm to everyone. With her the shaman has a child who he sees as a child but who everyone else sees as a jaguar. This jaguar-child lives in the shaman’s body as the embodiment of his ‘spiritual force.’

Both for the Mamaindê and for the Halotésu and other cerrado groups, shamanic initiation can be conceived as a process of dying. For the Negarotê, according to Figueroa (1989), the process of shamanic initiation, called a ‘dream vision,’ is equivalent to a form of reclusion: the initiate shaman remains inside a small house made from burity leaves especially for this purpose and during this period of reclusion receives “a degree of instruction from a mature shaman who uses songs and speech to summon the arrival of ancestors as protectors and helpers.”

This practice is not a kind of formal apprenticeship; rather, all the techniques of shamanism (sucking out pathogenic objects, blowing tobacco smoke, singing etc.) are learnt informally by observing the performance of other more experienced shamans. Inside the reclusion house, the initiate must consume large quantities of chicha (a fermented drink) previously prepared by women and proclaim that ‘many’ are drinking for him. Figueroa states that “the candidate sings, drinks and smokes ceaselessly, covers his body in annatto dye, wears burity decorations on the wrist and a soft cotton necklace, and may use cotton necklaces with jaguar teeth.”

As we have seen, for the Mamaindê, the episode of the encounter with the spirits in the forest can be considered the emblematic case of shamanic initiation. However, a person may also be initiated by an older shaman who, as they say in Portuguese, gradually “hands over the line” to him.

One of the shamans currently active in the Mamaindê village told me that he received his line (kunlehdu) from a shaman (now deceased) who had lived in his village. He gradually passed his ‘things’ on to him until he himself became a shaman. He said that the shaman’s necklace was usually stronger than that of other people, meaning it was less likely to break. As well as body decorations, he also received a number of objects from this older shaman: stones, jaguar teeth, a gourd, a bow, arrows and a wooden sword used to kill the forest spirits during the curing sessions. He also added that some years ago he received other ‘things’ (a stone and jaguar-tooth necklace) from a Kithaulhu shaman who was visiting the Mamaindê for a girl’s initiation festival to which the Kithaulhu had been invited.

Hence the novice shaman must always accompany an older shaman in order to learn everything he knows, especially the music for curing. At a determined moment, the older shaman will force the initiate to pass through a decisive test: he must spend an entire night alone in the forest without weapons. During this period, the shaman will send various animals (snakes, jaguars) to frighten him. However, he must see these animals as people and talk to them, asking them not to attack him. If he becomes frightened and runs away, the shaman will know and will not pass anymore of his ‘things’ on to him.

It is interesting to note that, in this case, the encounter between the shaman initiate and the animals sent by another shaman is not very different from the encounter with the spirits of the dead in the forest, cited above as the emblematic case of shamanic initiation. Here it is worth recording that, according to the Mamaindê, the spirits of the dead can transform into animals, especially jaguars. As we have seen, the spirit-woman who the shaman receives from the spirits of the dead is also described as a jaguar.

As he is extremely visible to the forest spirits, the novice shaman must take a series of precautions. As well as avoiding wandering to far away from the village so that his decorations are not stolen by other beings, he must also abide by a series of restrictions to ensure his body decorations and his spirit-wife remain with him. He must not eat hot food or blow on the fire, since the heat will scare away his spirit-wife and break his body decorations. He must also avoid heavy work or carrying heavy loads lest his decorations snap, and avoid talking loudly in case he scares his spirit-wife who will think he is fighting with her.

The shaman’s dietary precautions are primarily intended to establish and maintain the marriage with his spirit-wife who, as the Mamaindê say, “begins to eat with him always.” As well as dietary restrictions, the shaman must also limit his sexual activity, particularly extramarital sex, since his wife will become very jealous and hit him, snapping his body decorations.

The transmission of the decorations from one shaman to another is a reversible operation. Consequently, the possession of body decorations is never seen as a definitive condition or intrinsic attribute of the shaman, but, on the contrary, as an unstable condition that requires continual effort in order to be maintained. As a result, many people cease to be shamans, since they cannot bear the restrictions imposed on those who relate so intimately with the spirits of the dead.

The shaman’s work is therefore essential to the living, but extremely dangerous for the shaman. Those unable to withstand the restrictions needed to acquire and maintain shamanic power run the risk of dying as victims of the revenge of the spirits of the dead who, ceasing to act as their kin, begin to act as enemies, provoking accidents and illnesses.

Notes on the sources

The first ethnographic data on the Nambikwara are found in the publications of the Rondon Commission. These are reports made by Rondon and the employees who worked for the Telegraph Line Commission.

David Price (1972) mentions these reports and observes that most of them refer to the material culture and the geographic location of the different Nambikwara groups. According to him, the reports produced by Antonio Pyreneus de Souza (1920), the engineer responsible for transporting supplies to the telegraph stations, are the most interesting for anthropologists since they contain careful observations about the Nambikwara diet and day-to-day life. Price also cites the records made by travellers who passed through the region inhabited by the Nambikwara, but whose expeditions were not directly related to the Rondon Commission, such as Roosevelt and Max Schmidt.

In 1912, Edgard Roquette-Pinto, then professor of anthropology at the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, was the first ethnologist to visit the Nambikwara in the region of the Serra do Norte. He had already studied the material sent by the Rondon Commission to the Museu Nacional, containing various objects collected from diverse Nambikwara groups. In the book Rondônia, published in 1917 in the ‘Arquivos do Museu Nacional,’ Roquette-Pinto describes his experience among the Nambikwara and records important information on the material culture of these groups, mentioning the objects that were collected by him to expand the Museu Nacional’s collection. Roquette-Pinto also made visual records (on film) of two war festivals and sound recordings of Nambikwara musical pieces, two of which are transcribed in his book.

The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss stayed with the Nambikwara in 1938, living with different groups in their temporary encampments located close to the telegraph stations built by the Rondon Commission. In 1948, Lévi-Strauss published an ethnography of the Nambikwara entitled La vie familiale et sociale des indiens Nambikwara, which was partially published in Tristes Tropiques (1955), as well as various articles in which tackles a variety of themes on the basis of the ethnographic material relating to the Nambikwara: kinship, leadership, naming, the relation between warfare and trade in Amerindian societies, dualist systems of social organization, the notion of archaism in anthropology and shamanism. He also wrote the article on the Nambikwara included in the Handbook of South American Indians (1948).

In the expedition to Central Brazil, Lévi-Strauss was accompanied by the medic Jean Vellard, who published an article on the preparation of curare poison among the Nambikwara (1939), and by Luiz de Castro Faria, who published a book with his field notes and photographs from the expedition (2001).

In 1949, Kalervo Oberg visited the Jesuit mission in Utiariti, where he studied the Nambikwara group he named as ‘Waklitisu’ (i.e. Wakalitesu), numbering 18 people at the time. His work describes the social organization, religious practices and lifecycle of the Nambikwara.

Ten years later, Lajos Boglár visited Utiariti and, like Oberg, did not leave the mission. There he recorded Nambikwara music, later analyzed by Halmos. in 1968, René Fuerst collected artefacts from the Nambikwara groups of the Sararé valley, which were sent to museums in Europe.

The engineer Desidério Aytai conducted research with the Nambikwara in the 1960s and published a series of articles. Price wrote an article entitled ‘Desidério Aytai: o engenheiro como etnógrafo [the engineer as ethnographer]’ (1988), mentioning the work of this author who, though lacking anthropological training, recorded the flute music in detail, as well as aspects of bow making among the Nambikwara groups.

In August 1963, Aytai visited the Mamaindê. Between June and July 1964, he stayed with groups from the Sararé valley. In June and July 1966, he returned to the Mamaindê and, in July 1967, stayed with the Nambikwara of Serra Azul village (Halotésú) and with groups from the region drained by the Galera river (Wasusú). But it was at the end of the 1960s that studies involved long-term fieldwork began to be undertaken with Nambikwara groups.

In 1965, the anthropologist Cecil Cook of Harvard University began his fieldwork among the Nambikwara of Serra Azul and Camararé villages (cerrado groups) but unfortunately the results of his research were never published. I am only aware of an article he wrote with Price (1969), which offers a general panorama of the situation of the Nambikwara during this period.

David Price was the anthropologist who spent the most time in the field, between 1967 and 1970. Over a period of 14 months, he was able to visit almost all the Nambikwara territory and stayed in the villages of various groups. Price completed his doctoral thesis in 1972 at Chicago University and published numerous articles. He set up the ‘Nambikwara Project’ for FUNAI and returned to the Nambikwara villages between 1974 and 1976 as part of this work.

The Nambikwara Project primarily aimed to establish mechanisms for Funai’s work in the villages that would enable a reduction in the high mortality rate among the Nambikwara, as well as gathering information for the demarcation of new areas for these groups. Price also acted as a consultant for the World Bank, the financer of the Polonoroeste Project, in 1980, and in 1989 published a book on the basis of this experience.

Paul Aspelin conducted field research with the Mamaindê between 1968 and 1971. His work focused specifically on the productive system of the Mamaindê economy and resulted in a Ph.D. thesis successfully completed at Cornell University in 1975, as well as a number of articles on agriculture and the trade in artefacts among the Mamaindê.

More recent works on the Nambikwara include the doctoral thesis by Alba Lucy Figueroa on anthropology applied to healthcare work among the Negarotê, the master’s dissertation by Marcelo Fiorini on the notion of the person and naming among the Wasusu, and the works of Anna Maria Ribeiro Costa on the Nambikwara groups of the cerrado.

There are also two important articles on Nambikwara music: Avery’s article on Mamaindê vocal music and Lesslauer’ article, ‘Aspectos culturais e musicais da música dos Nambikwara [Cultural and musical aspects of Nambikwara music]’ (1999). In the latter article, the author provides a good summary of what had been written on the Nambikwara to date.

Mention should also be made of the works produced by missionaries from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (Peter Kingston, Bárbara and Menno Kroeker, Ivan Lowe and David Eberhard) on Nambikwara languages and the publications of the Jesuit priest Adalberto de Hollanda Pereira, who recorded various myths from Nambikwara groups of the Juruena valley.

Sources of information

- ASPELIN, Paul L. External Articulation and Domestic Production: the artifact trade of the Mamaindê of northwestern Mato Grosso, Brazil. Tese de doutorado, Cornell University. 1975.

- ______. “Nambiquara economic dualism: Lévi-Strauss in the garden, once again”. In: Bijdr. Taal, Land-Volkenkunde, 1976, 132 (1): 1-31.

- ______. “Comments by Aspelin”. In: Bijdragen toto de Taal-land en Volkenkunde s.l., 1978, 134: 158-61.

- AVERY, Thomas L. “Mamainde Vocal Music”. In: Ethnomusicology, Sept. 1977, n. 3, p.p.359-377.

- AYTAI, Desidério. “As flautas rituais dos Nambikuara”. In: Revista de Antropologia (São Paulo), 1967-8, separata do vol. 15/16: 69-75.

- ______. “Um mito Nambiquara: a origem das plantas úteis”. In: Publicações do Museu Municipal de Paulínia, 1978, 17:6-17.

- ______. “Apontamentos sobre o dualismo econômico dos índios Nambikuara”. In: Publ. Museu Municipal de Paulínia, 1981, 15:13-30.

- BOGLÁR, Lajos. “L’Acculturation des Indiens Nambikuara”. In: Annals of the Náprstek Museum. 1962, 1:19-27.

- ______. “Contributions to the sociology of the Nambikuara Indians”. In: Acta Ethnographica, 1969, 18:237-246.

- _______. “Nambiquara – a brazilian ‘marginal’ group?”. In: Sep. Sonderabdruck aus Néprajzi értesitõ, Budapest. 1972, v. 54, p. 217-222.

- BOGÁR, Lajos & HALMOS, István. “La flûte nasale chez les indiens Nambicuara”. In: Acta Ethnographica, 1962, 11:437-446.

- CASTRO FARIA, L. Um outro olhar: Diário da Expedição à Serra do Norte, Rio de Janeiro: Ouro sobre azul, 2001.

- COSTA, Anna Maria Ribeiro. “A flauta sagrada. Índios Nambiquara”. In: Publicações do Museu Histórico de Paulínia, 1991, 49:52-55.

- _______. “A menina-moça: ritual nambiquara de puberdade feminina”. In: Publicações do Museu Histórico de Paulínia. 1991, 51:90-95.

- _______. Senhores da memória: uma história do Nambiquara do cerrado. UNICEN Publicações/UNESCO, Cuiabá, MT., 2002.

- EBERHARD, David Mark. Mamaindê Stress: the need for strata. Publ.: Summer Institute of Linguistics and Univ. of Texas at Arlington. 1995, Publication 122.

- FIGUEROA, Alba Lucy Giraldo. Comunicação intercultural em saúde: subsídios para uma ação social em educação indígena. São Paulo: USP, 1989. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- FIORINI, Marcelo O. Embodied Names: construing Nambiquara personhood through naming practices. New York University, 1997. (Dissertação de mestrado)

- GARVIN, Paul L. “Esquisse du système phonologique du Nambikwara-Tarunde”. In: Journal de la Societé des Américanistes de Paris, 1948, 37:133-189.

- HALMOS, István. “Melody and form in the music of the Nambicuara Indians (Mato Grosso, Brazil)”. In: Studia Musicologica, 1964, 6:317-356.

- ______. “The music of the Nambiquara indians (Mato Grosso, Brazil)”. In: Acta Ethnographica, Budapest, 1979, 28 (1-4): 205-350.

- KROEKER, Barbara J. “Morphophonemics of Nambiquara”. In: Anthropological Linguistics. 1972, 14:19-22.

- LESSLAUER, Claude. “Kulturelle und musikalische Aspekte der Musik der Nambiquara, Mato Grosso, Brasilien”. In: Die Musikkulturen der Indianer Brasiliens: II, Roma: consociatio Internactionalis Musicae Sacrae, 1999, p. 267-393.

- LÉVI-STRAUSS, C. “The social and psychological aspect of chieftainship in a primitive tribe: the Nambikuara of north-western Mato Grosso”. Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1944, Series II, 7(1):16-32.

- _______. “The name of the Nambikuara”. American Anthropologist. 1946. vol. 48(1): 139-140.

- _______. “La vie familiale et sociale des indiens Nambikwara”. Paris, Société des Américanistes. 1948.

- _______. “Sur certaines similarités structurales des langues Chibcha et Nambikwara”. Actes du 28e Congrès International des Américanistes, Paris. 1948, 185-192.

- ______. “The Nambiquara”. Steward, J. (Ed). Handbook of South American Indians. New York, Cooper Square. 1948, v. 3, p. 361-369, Smithsonian Instituitio, Bureau of American Ethnology, 134.

- ______. "Guerra e comércio entre os índios da América do Sul". SCHADEN, E. (Ed.), Leituras de etnologia brasileira, São Paulo, Cia. Editora Nacional, 1976 [1942], p. 325-39.

- ______. “Comments”. Brijdragen toto de Taal-Landen Volkenkunde. 1976, s.l. 132: 31.

- ______. “Comments”. Brijdragen toto de Taal-Landen Volkenkunde. 1978, s.l. 134: 156-158.

- ______. Saudades do Brasil, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1994.

- ______. Tristes Trópicos, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1996 [1955].

- MILLER, Joana. “As Coisas. Os enfeites corporais e a noção de pessoa entre os Mamaindê (Nambiquara)”. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social – Museu Nacional/ UFRJ, 2007. (Tese de doutorado)

- OBERG, Kalervo. “Indian Tribes of Northern Mato Grosso, Brazil”. In: Smithsonian Istitution: Institute of Social Anthropology Publication n. 15, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1953.

- PEREIRA, Adalberto Holanda. “A morte e a outra vida do Nambikuara”. Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisa, Antropologia, 1974, n. 26, São Leopoldo – RS.

- ______. “O pensamento mítico dos Nambikuara”. Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas, Antropologia, 1983, n. 36. UNISINOS – São Leopoldo, RS.

- PRICE, David. “The present situation of the Nambiquara”. Sep. American Anthropologist, 1969, 71 (4):688-693.

- ______.Nambiquara Society. University of Chicago, 1972. (Tese de doutorado)

- ______. “Comercio y aculturación entre los Nambicuara”. América Indígena, 1977, 37 (1): 123-35.

- ______. “The Nambiquara linguistic family”. Anthropological. Linguist., 1978, 20 (1): 14-37.

- ______. “Real toads in imaginary gardens: Aspelin vs. Lévi-Strauss on Nambiquara nomadism”. In: Bijdr. Taal, Land-Volkenkunde, 1978, 134 (1): 149-56.

- ______. “Nambiquara lidership”. In: American Ethnologist, 1981, 8 (4):686-708.

- ______. “The Nambiquara”. In: Culural Survival. Occasional Paper, 1981, 6:23-31.

- ______ . “Earth people”. In: Parabola, 1981, 6 (2): 15-22.

- ______. “A reservation for Nambiquara”. In: Hansen, A. & Oliver-Smith, A., (Ed.), Involuntary Migration and Resettlemente; Westview Press, 1982, p. 179-199.

- ______. “La pacificación de los Nambiquara” In: America Indigena, 1983, 43 (3): 601-628.

- ______. “Pareci, Cabixi, Nambiquara: a case study in western classification of native peoples”. In: Journal de la Societé des Américanistes. Musée de L’Homme, Paris, T. 1983, 69, pp. 129-148.

- ______. “Nambiquara Brothers”. In: Working Papers on South American Indians. The sibling relationship in lowland South America. Bennington, Bennington College, 1985, (7): 16-19.

- ______. “Nambiquara Languages: linguistic and geographical distance between speech communities”. In: Flein, Harriet, Menelis & Stark, Luisa R. (eds.), South American Indians Languages. Austin, Univ. of Texas Press, 1985, pp. 304-324.

- ______. “Nambiquara Geopolitical Organization” In: Man: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 1987, 22(1): 1-24.

- ______. Before the Bulldozer: The Nambiquara Indians and the World Bank, Seven Locks Press, Washington, D.C. 1989.

- ______. “A Nambiquara puberty festival: the onset of female puberty is regarded as a maiden’s passage to womanhood and os celebrated by the Nambiquara of Brazil with a festival of dance and song”, s.n. In: Sep.: The World, may, 1989. pp. 678-689.

- PYRINEUS DE SOUZA, Antônio. “Notas sobre os costumes dos índios Nhambiquaras”. Em: Revista do Museu Paulista, o.s. , 1920, 12:391-410.

- RONDON, C. M da S. “Ethnographia”. CLTEMTA. Anexo 5. História Natural, Rio de Janeiro, 1910, 57 p.

- ______. Estudos e reconhecimentos. Rio de Janeiro, Papelaria Luiz Macedo. Relatórios, s/d, 365 p. (Comissão Rondon, 1).

- ______. Relatório parcial correspondente aos anos de 1911 a 1912, 2., Rio de Janeiro, 1915, 346p. (Comissão Rondon, 26).

- ______. Apontamentos sobre os trabalhos realizados pela CLTEMTA, de 1907 a 1915. s.n.t, s.d.

- ______. Conferências realizadas em 1910 no Rio de Janeiro e S. Paulo. In: CLTEMTA. Pub. 68, Rio de Janeiro, typ. Lenzinger, 1922.

- ______. Índios do Brasil. vol. I do centro, noroeste e sul de Mato Grosso. Rio de Janeiro. Conselho Nacional de Proteção aos Índios, 1946.

- ______. História natural – ethnographia, Rio de Janeiro, 1910. 1947, p.49-57, (Comissão Rondon, 2).

- ______. Glossário geral das tribos silvícolas de Mato Grosso e outras da Amazônia e do Norte do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro. Conselho Nacional de Proteção aos Índios. Pub. 1948, n. 76.

- ROOSEVELT, T. Nas selvas do Brasil. São Paulo, EDUSP e Itatiaia. 1976, 226p.

- ROQUETTE-PINTO. Rondônia. 6ª Edição. São Paulo, Editora Nacional; Brasília. 1975 [1917].

- SETZ, Eleonore Zulnara Freire. Ecologia Alimentar em um Grupo Indígena: Comparação entre aldeias Nambiquara de floresta e de cerrado. Dissertação de Mestrado em Biologia (Ecologia), Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, SP, 1983.

- VELLARD, J. “Préparation du curare par les Nambikwara”. In: Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 1939, 31:211-221.

- ______. Histoire du curare. Paris, Gallimard, 1965.