Ingarikó

- Self-denomination

- Kapon

- Where they are How many

- RR 1728 (Coping, 2020)

- Guiana 4000 (, 1990)

- Venezuela 728 (, 1992)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

The Ingarikó inhabit the area surrounding Mount Roraima, the dominant landmark on the triple border between Brazil, Guiana and Venezuela, and, above all, the stump of the mythological tree of life, which was chopped down at the beginning of time. Occupying the highest portion of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, they remained free of the various forms of recruiting indigenous labour that affected neighbouring peoples to the south for centuries. Contacts with their relatives in Guiana are today, as in the past, fairly frequent.

Names

Engaricos is the oldest form – dating from 1883 – of writing the name, later almost invariably written as ingarikó. At the time it was said to designate, in Guiana, a hybrid mixture of Makuxi and Arekuna, rather than a unique people (Im Thurn).

Forty years later, the name ingarikó was translated in Brazil as “people from the dense forest” of the northeast of Roraima, a term with a pejorative connotation: people who formed the main common enemy of the Taurepang and Arekuna (Koch-Grünberg 1924). During this period, the referent of the term ingarikó was an open question. Hypotheses ranged from the name referring to a particular people located on the Brazilian side of the triple border between Brazil-Guiana-Venezuela, perhaps linked to the Akawaio of Guiana, to the idea that the name was applied indiscriminately to the Patamona and Akawaio living in Guiana, considered two separate peoples (Frank 2002).

In the 1980s the term ingarikó was glossed as “people from the peak of the mountain,” this time without a pejorative connotation. Before this anthropologists already knew that those called the Ingarikó in Brazil and the Akawaio and Patamona in Guiana were one and the same people, who could be designated by the term kapon. It was understood that, in light of the meaning of the name ingarikó, the term could also be applied to the Akawaio and Patamona, given that they live almost exclusively in upland areas (Butt Colson 1983-1984). This means that the term ingarikó can be used in a variety of contexts by themselves and by others. In practice it means that the same person can, according to circumstances, identify him or herself, whether in Brazil or elsewhere, either as Patamona or as Ingarikó. Currently the Patamona living in Brazil tend to identify themselves as Ingarikó in the context of national policies. Only in Brazil does the name ingarikó have a national significance.

More recently a third translation for the name ingarikó was presented: “people from the cold and dry place.” The term is used in this sense by the Macuxi who live in Guiana vis-à-vis the Patamona, who also inhabit the country (Whitehead 2003).

A contemporary linguistic analysis gives the following: “descriptively ingarïko is: inga 'mouintain range,’ 'thick forest;’ rï- 'connecting element;’ -ko 'collective: origin, place of inhabitants,’ ‘inhabitant of,’ ‘resident of,’ hence ‘people from the thick forest,’ ‘mountain dwellers’” (Maria Odileiz Sousa Cruz).

The term kapon was taken as a self-denomination of the Ingarikó, Akawaio and Patamona by various authors (Brett; Im Thurn; Kenswil; Butt Colson). Among the meanings of kapon are: ‘people,’ ‘the people,’ or better, ‘celestial people,’ ‘people of the heights,’ ‘high people’ (kak, ‘sky,’ ‘elevated place’ and -pon, ‘those in’).

It should be noted that today this term may also designate ‘Indians’ (Macuxi, Waiwai, Yanomami, Ingarikó etc.), specifically in contexts in opposition to ‘non-Indians.’ Hence the term is not a self-designation. However, given the absence of a more suitable term for designating ampler social or linguistic units formed exclusively among the Ingarikó, Akawaio and Patamona, researchers have used the term kapon. This led to the introduction of the composite names: Kapon-Ingarikó, Kapon-Patamona and Kapon-Akawaio.

The name akawaio has a large number of synonymous variations: guacavayo, okawalho, wakawaio, akawoi, accoway, acquai, acawey, acuwey and akawaïsche. The name akawaio seems to derive either from the tobacco juice, kawai, ingested by shamans (Migliazza 1980) or the ‘white cinnamon,’ akawoi, sought by the Dutch in Guiana (Whitehead 2002). This plant was found in the Pacaraima Mountain Range and the valleys of the Cuyuni and Mazaruni rivers. The first record of the term Wacawaios was made in 1596 by Laurence Keymis on the Demerara river (Butt Colson 1994-1996). However the first observation of the presence of the Akawaio in Brazil was only made in 1909 by the German botanist Ernst Ule, who called them Okawalho (Ule 2006). After this, around 1960, it was recorded that the Akawaio stretched from Guiana to Brazil (Henfrey).

The name patamona also has several synonymous variations: pantamona, partamona and paramona. The term means ‘inhabitant,’ ‘dweller’ (Butt Colson 1983-84) and ‘owners of the land’ (Whitehead 2003). The term patamona can be described as follows: pata ‘house,’ ‘dwelling’ (generic term) and wona>mona ‘to,’ loosely meaning ‘my house,’ ‘my dwelling place,’ ‘to house’” (Maria Odileiz Sousa Cruz). The first reference to this term was made in 1825 by the Indian inspector in Guiana, William Hilhouse. However the first reference to the presence of the Patamona in Brazil dates from as late as 1932 (cited in Nunes Pereira).

The name Waica or Guaica means ‘warrior or ‘killer’ and is widely disseminated (Butt Colson 1994-1996). As the designation of an Akawaio subgroup from Guiana, it was first recorded by R. Schomburgk (1848a). Much earlier the Spanish missionary Antonio Caulin had already located the Guaica in Guiana around 1780 without, though, relating them to the Akawaio, who he called Guacavayos. The term Guaica is frequent in the eastern region of Venezuela, as can be seen in the works of Capuchin missionaries from the second half of the 18th century onwards. By the 20th century, though, it was considered another name for the Akawaio in Venezuela (Mosonyi).

Other names – Seregong, Kukuyikó, Kuyálako, Kakóliko, Pulöiyemöko, Temómökó, Alupáluo, Ateró, Wauyaná, Arenacottes, Erena-gok, Masalini-gok, Kamalini-gok, Quatimko, Etoeko, Passonko, Koukokinko, Cauyarako, Skamana, Komarani and Yaramuna – are composed from the name of the river on whose shores the group lives or the name of the area inhabited, frequently combined with the suffix kok (-gok; -koto; -goto), meaning ‘inhabitant’ or ‘people of a particular location.’ This form of ‘fluvionymy’ is found among the Kapon on all sides of the Brazil-Guiana-Venezuela border, forming the contemporary way in which people identify themselves within the local context.

Language

The Ingarikó, filled with the political spirit acquired over the last 10 years, are seeking to obtain recognition of their dialect as a separate language. However new studies on the three dialects may furnish other information and criteria that could alter the present demand. In addition, as language is a dynamic process, today the seven Ingarikó villages reveal the presence of various sub-dialects.

As well as the dialects, the speakers of Ingarikó also understand and establish clear and direct communication with speakers of Taurepang and Arekuna (Pemon Indians who live in neighbouring areas). Nonetheless, although the Ingarikó manage to speak and understand the Makuxi language (also from the Carib family), its speakers cannot understand Ingarikó very well. It is only after some time living together that the Makuxi manage to acquire a certain level of comprehension of Ingarikó. Despite the ‘political-linguistic domination’ that the Makuxi attempt to impose on the Ingarikó, linguistic features also hinder the easy learning of Ingarikó by Makuxi speakers.

Another important aspect of the language is gender distinction. The difference between men’s speech and women’s speech is present in some kin terms, such as the terms for ‘daughter’ [mïre for a woman and ensi for a man] and ‘older brother’ [pipi and rui, respectively].

The same phenomenon occurs in the sphere of the Hallelujah religion, an occasion when certain honorary titles are applied to the men – such as tïkarinin, ‘he who cuts meat’ – and others to women – pasiko, ‘sister.’ All these names relate to the social functions and roles already conventionalized in the ritual. The Ingarikó believe that the Hallelujah rite also commands the ‘gift’ of the language spoken by them.

Ingarikó is a language of intense vitality, spoken by all the members of the different villages – children, youths, adults and old people.

Alongside the indigenous languages, Portuguese is also strongly present in the Ingarikó villages. The language has spread rapidly through the region over the last ten years and the context of few bilingual speakers has already changed. The change from monolingualism, still predominant among the older generation, to bilingualism and plurilingualism is due especially to the role of young people in the communities. In general as well as the indigenous languages the latter speak Portuguese, Spanish and English. This situation was generated by the multiple social contacts and by the school.

Location

The Kapon (Ingarikó, Patamona and Akawaio) inhabit an area divided between Brazil, Guiana and Venezuela, surrounding Mount Roraima, the region’s highest mountain, marking the triple border. In Brazil the Ingarikó and the Patamona occupy an upland region of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, located in the northeast of Roraima state.

The population is distributed in 7 villages along rivers and creeks with the highest demographic concentration on the upper Cotingo river and on the Ponari. They are closer to Mount Roraima than their neighbours to the south, the Makuxi, Taurepang and Wapixana, with whom they share this Indigenous Territory.

In Guiana the Akawaio inhabit the middle and upper course of the Mazaruni river and its affluents and the Cuyuni river. The Patamona, for their part, are located in the Pacaraima Mountain Range and along the Ireng (Maú) river on the border with Brazil. Both are located in upland areas of Guiana. In Venezuela the Akawaio are situated in the east of Bolívar state on the border with Guiana, close to the Wenamu river.

Further reading

To learn more about the demarcation process for the Raposa Serra do Sol IT, see ISA’s special report.

Population

According to the survey presented at the 7th General Assembly of the Ingarikó People in 2005, the Ingarikó population was approximately 1,120 people, or around 8% of the total population of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT.

In 2007 the Ingarikó numbered around 1,170 people.

The table below shows the population distribution in the seven Ingarikó villages between 1992 and 2007:

| Village name | Population in 1992 | Population in '2007 |

| Serra do Sol | 186 | 330 |

| Manalai | 178 | 344 |

| Kumaipá | 69 | 145 |

| Mapaé/Caramãbatei | 57 | 143 |

| Sauparu | 56 | 89 |

| Awendei/Canauapai | 40 | 82 |

| Pipi | 28 | 37 |

| Total | 614 | 1170 |

Sources: Data from the CIDR (Roraima Diocese Information Centre) from 1992 (in Abreu 2004) and Coping - 9th General Assembly 2007.

The largest section of the population is formed by children followed by young people and adults. In 2000 individuals aged over 60 years old comprised less than 5% of the population. It can be observed from the table that the Ingarikó population practically doubled over a fifteen year period.

History of contact with non-Indians

No precise information exists on the first contacts of the Ingarikó with non-Indians on the Brazilian side of the border. It is known that in 1932 the Boundary Demarcation Commission was in contact with the Patamona of the Maú (Ireng) river on the Brazilian side, in the area between the mouth of the Timã creek and the Ireng-Scobi confluence.

Still in the 1930s, Benedictine priests, in particular Dom Alcuino Meyer, entered into contact with the Ingarikó in the Serra do Sol village and in other more remote villages.

The first scientific expedition reached the Ingarikó in 1946. The team was composed of Nunes Pereira, then an employee of the Ministry of Agriculture, and the US ornithologist G. Tate. Nunes Pereira explained the objectives of his own research thus: “to learn about the ecological conditions enjoyed by the Taulipangue and Ingaricó Indians and to obtain data on the ichthyological fauna of the Cotingo river and nearby creeks in the Uêitêpêi and Roroima Mountain Ranges.” They set out from Boa Vista without being able to obtain numerical data on the Ingarikó population from the Benedictines, since the missionaries only had data for the Macuxi and Wapixana. Nunes Pereira was responsible for the first photographic images of the Ingarikó. These comprise five photographs taken in the village of the ‘tuxaua’ (chief) Jones in the foothills of the Uêitêpêi mountains. The caption to three of the photos reads ‘Dancers of the Aleluia Dance,’ but the same photos are cited elsewhere as the ‘Parixara Dance.’ The photos as well as Nunes Pereira’s observations were made public only in 1967 in the book Moronguetá.

In the 1950s the priest Bindo Meldolesi of the Ordem da Consolata reached the Ingarikó of the Serra do Sol a few times without, though, taking plans for establishing a mission.

Between 1952 and 1964, Atlas Brasil Cantanhede, an agronomist and civil air pilot known as the pioneer of aviation in Roraima, made regular trips to Serra do Sol as part of the rubber extraction in the area. An Ingarikó man worked for him for some years during which time he learned Portuguese.

The 1970s saw a surge of prospecting in the upland region of the Macuxi area with miners reaching the Ingarikó. However they were forced to retreat, settling in the locality of Caju, one day’s horse ride from the Serra do Sol village. Caju was a non-indigenous mining site with a landing strip and some stores selling food, drink and tools. The Ingarikó visited the site regularly but refused to allow the non-Indians to enter their area. Around this time a trader from Caju tried various times to install a cattle ranch close to the Serra do Sol village. The Ingarikó drove away the cattle and burnt down the farmhouse.

Also in the 1970s, priests from the Ordem da Consolata visited the Ingarikó. Father Jorge Dal Ben undertook three journeys during which time he was in contact with all the villages in the area.

From 1975 onwards FUNAI began to make regular flights to the Serra do Sol village. The FAB (Brazilian Air Force) for its part was already making border control inspections.

In 1976 the anthropologist Orlando Sampaio Silva was informed of the continued isolation of part of the Ingarikó as well as the sporadic contact of another group with missionaries from the Assembly of God Evangelical Church in Serra do Sol. He also recorded the presence of a few of the Ingarikó at the São Marcos Farm.

National park in areas of indigenous occupation

At the end of the 1980s the Ingarikó, though distant from the direct conflicts involving squatters, smallholders, ranchers, rice farmers and indigenous populations living in the south of the region now forming the Raposa Serra do Sol IT, began to experience a new type of pressure on their lands.

Om June 28th 1989 the Mount Roraima National Park was created, overlapping a section of the territory traditionally occupied by the Ingarikó (two villages are located within the Park and another seven are situated in the surrounding region). Fifteen days earlier the Ingarikó Indigenous Area had been declared by the Interministerial Group and, in parallel, the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT (whose territory includes the are now occupied by the Ingarikó) was still in progress. It is fairly evident that the creation of the Park was much more a political strategy than an action based on prior technical data.

The pressure suffered by the Ingarikó arises, therefore, from the federal legislation itself, since the legal category of Full Protection (Conservation Unit) in which the National Park is included has serious implications for the life of communities whose territories overlap that of the Park. The conflicts emerge especially around the issue of the usage restrictions established by Ibama’s Management Plan.

The Ingarikó only learnt about the existence of the Mount Roraima National Park and the conflicts relating to the situation generated by the overlapping areas during a FUNAI mission in September 2000. A ‘participative workshop’ was held with three Ingarikó representatives during which the Park management plan was elaborated. According to a statement by a key indigenous leader, although they had taken part, the Ingarikó attending the workshop had not in fact understood the implications that the implementation of the National Park could have for their way of life.

Hence a new conflict was generated in the Raposa Serra do Sol IT as a result of the overlapping of the Conservation Unit/Indigenous Territory. This is far from being an isolated case in the country. It probably gained more visibility because of the conflicts relating to approval of the Raposa Serra do Sol IT. However, the discussion on the overlap of areas in the Mount Roraima region was pushed into the background by the conflicts existing in the south of the IT.

Although many documents emphasize the opposition of the Ingarikó to the implementation of the National Park and also indicate a consequent legal-institutional conflict between the Indians and IBAMA, what now exists is a negotiation process, which culminated in the indigenous assemblies held in 2005, especially in the wake of the decree ratifying the Raposa Serra do Sol IT on April 15th 2005.

The term Double Allocation was used in the text of the decree to clarify the legal condition of the Mount Roraima National Park. The idea contained in this term is that of the coexistence in the same space of a National Park and an Indigenous Territory, and the need for a management plan to be elaborated by the federal environmental and indigenist agencies alongside the Ingarikó community.

In 2005 a new phase was inaugurated in the political debate on the question of double allocation, which was boosted by the strengthening of the political organization of the Ingarikó (with the new prospects for alliances) and by the deepening of the discussions on the overlap situation for the management of the territory in question.

The document produced at the 7th General Assembly of the Ingarikó, held between the 18th and 21st of April 2005 in Serra do Sol village, sets out the group’s concern with: the sociocultural changes under way, the problems existing within the communities, the conflicts relating to the demarcation of the RSS IT and its impacts on the relations between the villages, as well as their autonomy in light of the legal situation of overlapping federal areas of protection. The text also emphasizes the intention to obtain recognition of the cultural specificity of the Ingarikó so as to enable the implementation of specially designed actions.

Social organization

The Ingarikó villages in the Raposa Serra do Sol IT are made up of a variable number of habitations, ranging from the smallest with two houses to the most extensive, which may contain several dozen family units.

At first sight the layout of these villages seems haphazard. They involve a central clearing around which are built a number of houses, arranged in an apparently random form, frequently along the river shores. Examining more carefully, however, shows that these houses are grouped in small clusters that, composed of groups of close kin, constitute various nucleuses of more intimate coexistence.

The Ingarikó, like the other peoples from the Carib language family in the Guiana region, have a strong uxorilocal tendency: in other words, the traditional practice of marriage associated with the subsequent residence of the couple in the village of the wife’s family.

According to this rule, women after marriage remain living in their village of origin, while the men relocate in space and within social life as a whole. As soon as they marry, the young husband moves to live with the woman’s family, providing services to her parents, especially his father-in-law, bringing game and fish and helping with swidden work, building or repairing the house, gathering various plant fibres and making items for household use such as baskets, mats, sieves, tipiti manioc presses, and various other objects.

Each local group is organized around the figure of the leader/father-in-law on whose political skill in manipulating kinship the stability of the village depends. When the couple’s first children have grown, the new family establishes its own area of cultivation and begins to live in another house, consolidating a new, relatively autonomous domestic group.

Following the growth of the kingroups with the marriage of younger generations the local group tends to assume other forms, such as for example a series of siblings residing in the same location alongside their respective families. When the growth becomes excessive or the leader dies, the local group may dissolve with the return of the married men to their villages of origin together with their families.

Hallelujah ritual

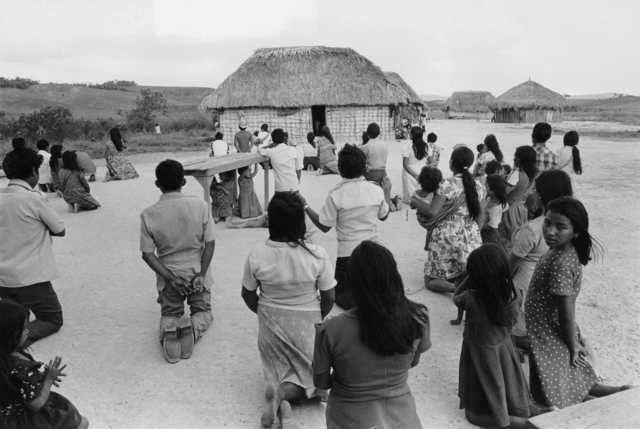

It is not rare for us to encounter, among the indigenous peoples of South America or elsewhere, the use of a special language – of foreign, archaic or artificial origin – during ritual performance. Very often many words or even the entire language are incomprehensible to those speaking them in the rituals. This is not a symptom of disorganization, loss of memory or acculturation. Neither is it necessarily evidence of syncretism or mimetism. The Aleluia ritual presents us with this complexity from the outset. The word hallelujah (aleluia) is used by the Kapon themselves (Ingarikó, Akawaio and Patamona) to designate a ritual that will only be fully performed with the arrival of the general cataclysm and the white messiah.

Presented below is an outline of the history of the word hallelujah among the Kapon and neighbouring peoples. This is followed by a description of the rite.

Outline of a history of the word hallelujah

The word hallelujah was first recorded in the first half of the 19th century in the song of an Indian living on the Corentyne river, on the border between Guiana and Suriname. This was in 1839. At the time the Anglican missionaries had just arrived in Guiana. On a reconnaissance trip to the area, Bishop Coleridge wrote (Farrar 1892:55-56):

"One time on the Corentyne river I heard an old blind chief sing hallelujah time and again, in a soft and whining cadence, whenever he completed the verse of a sacred hymn taught to him by the Moravians in his youth."

This old blindman, Nathaniel, is depicted as “the last relic,” “the last surviving disciple of the Moravian brothers".

Based on this first record we can reconstruct the process of catechism during the Dutch colonization in Guiana, though not without first stressing that the Dutch indigenist policy did not look to convert the Indians or settle them in mission villages, but to establish trade relations with them. This catechism was undertaken by the German Moravians. They established three missions focused primarily on the Arawak (Lokono) and Carib (Karinya): the Pilgerhut mission on the Essequibo river between 1740 and 1763; the Ephraim mission on the Corentyne river, shut down soon after its inauguration in 1757; and the Hoop mission on the Suriname side of the Corentyne between 1765 and 1806, transferred to the Guianese side between 1812 and 1816.

The Moravian missionaries devoted themselves to intense study of the Arawak language (Lokono) and ended up translating numerous hymns and Bible passages into the native language, as well as producing an Arawak(Lokono)-German dictionary. What interests us, though, is the relationship with the Akawaio. The documentation available at the present time consists of diaries from the first mission, Pilgerhut, only. The first contact between the Akawaio and the Moravians took place in 1743 on the Berbice river, an encounter repeated various times on the same river between 1748 and 1749. It is also known that the Akawaio were among the Arawak who arrived at the Pilgerhut mission in 1751, where they were baptized. In addition the Morávios already had at that time an Akawaio preacher called Ruchama (Butt Colson 1994-1996).

For the subsequent period that leads us to the most important mission, Hoop (Hope), located on the Corentyne river, the information is even sparser. While the history of the Moravians in Guiana is starting to be studied in studied in more depth, we are missing almost a century of history between mid 18th century and 1839. Although we do not know whether the chief who sang Hallelujah in 1839 was Carib (Karinya) or not, we do know that the Kapon followed prophets from other peoples too and spread from east to beyond the western border of Guiana. In the 18th century there are reports of outbreaks of prophetism involving the Akawaio. Here we can already spot the emergence of the themes of the Indians transforming into whites and the return of the dead back to life. The earliest outbreak, observed in 1756, would lead in turn to an examination of the catechism undertaken by the Capuchins in Venezuela, the possible epicentre of the outbreak.

The second recording of the word takes us to the end of the 19th century. In 1884, the colonial agent Everard Im Thurn witnessed “an absolutely incessant cry of Hallelujah! Hallelujah!” which lasted from one sunset to the next, accompanied by large amounts of drinking. This occurred in the foothills of Mount Roraima, on the Guianese side, in the village of a people linguistically and culturally close to the Kapon, the Arekuna (Pemon).

Between the first and second recording of the word hallelujah there are reports of five outbreaks of prophetism in the area around Mount Roraima and on the Essequibo and Demerara rivers, as well as accounts of two migrations of the Kapon, and on a smaller scale the Makuxi, Arekuna and Maiongong, to the coastal Anglican missions among the Arawak (Lokono) in the northwest of Guiana. This period is well documented in Guiana. Here we can glimpse a prophetism movement common to the Kapon and Pemon based on the following main elements: terrestrial cataclysm by water and fire, skin changing, change of language, the end of work, the figure of the messiah and that of the white (or other) prophet, death at the hands of the followers of the prophet as a means to transformation, and, finally, the demand for books or papers. The latter demand is one of the more obscure points. The prophets had distributed papers in 1840 and 1845.

The migrations of the Kapon to the coastal missions, which heavily surprised the missionaries, were strongly linked to this demand for paper. In this context we can highlight a young Kapon man who stayed for around ten years from 1853 onwards at the Pomeroon mission were catechization was made in Arawak (Lokono) before moving to a Carib (Karinya) village with the idea of producing a translation into the Kapon language of the Carib (Karinya) version of the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, made years earlier by the Anglican missionary W. Brett.

W. Brett and the young Philip ended up working together on the Kapon translation on the coast of British Guiana for about a year. This resulted in the distribution of small books printed in the Kapon language and illustrated with Biblical passages to various villages. On one hand, this provoked the second flow of the Kapon and neighbouring peoples to the coastal missions between 1863 and 1869 and, in the case of the missionaries, a shift in their attentions to the central region of Guiana. This led to the expansion of catechism as far as the headwaters of the Demerara and Essequibo rivers where two missions were founded, Eneyuda and Muritaro. These were followed by another three on the Mazaruni, Cuyuni and Essequibo rivers. Though the missionaries had already declared themselves surprised by the openness of the Kapon to catechism, the Patamona of the Potaro river would consolidate the hypothesis of spontaneous conversion completely. Arriving in this difficult to access area in 1876, the missionaries discovered that the Patamona were already chanting, in the Kapon language, the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed and the Ten Commandments.

At the start of the 20th century the word hallelujah already carried a considerable weight. It was the designation given by the Kapon and Pemon to a ritual common to both peoples. For observers of the first decades of the last century, however, this was an ‘atypical dance,’ a ‘strange dance,’ a ‘strange religion’ or a ‘crazy religion.’ Nonetheless in June 1977 the Council of Churches of the Republic of Guiana officially incorporated Hallelujah as a member, and on October 21st the Government of the Republic of Guiana approved the association. The Anglican Church was responsible for the initiative.

In Brazil Hallelujah was examined with different degrees of interest by three researchers: Nunes Pereira and Stela Abreu among the Ingarikó, and Koch-Grünberg among the Taurepang (Pemon); in Guiana, it was studied among the Akawaio and Patamona by seven observers: C. Cary-Elwes, Frederick Kenswil, Michael Swan, Colin Henfrey, Audrey Butt Colson, Susan Staats and Neil Whitehead; and in Venezuela by David Thomas among the Pemon.

On the three sides of the triple border, the intensity of the dancing in Hallelujah also drew the attention of observers. On the Brazilian side, “many of the dancers fall into a trance, like in spiritist sessions, candomblé and macumba,” wrote Nunes Pereira in 1946. During the same period, on the Guianese side, “they sang and danced with such a frenzy that men and women became hysterical and began to shout and roll about on the ground,” reports F. Kenswil. And in Venezuela, “although none of the participants went as far as to faint, many required assistance since they were in a state close to trance as they jumped about, impelled by a mild frenzy. There is no doubt that as an intense form of dance,” writes D.Thomas, “this jumping step represents a type of catharsis and almost pushed some of the participants into a state of trance.” Among the Pemon too, on the Brazilian side, “sometimes the first dancers circle once and then the two semi-circles dance for a short time in front of each other, since one half walks forwards and the other backwards, throwing the upper part of the body violently forward or backward,” wrote Koch-Grünberg.

Hallelujah ritual

Among the Ingarikó Hallelujah is a rite of passage to the celestial layer by means of a messiah bench. It is not a invocatory rite. No action can prevent the coming conflagration, nothing can alter its course. The Hallelujah rite is rather the means of fleeing the water that burns, paraw, whose arrival will be announced in advance by the prophet. Hallelujah produces a double change of skin and a change of language.

The ceremonies held today are incomplete given that we are not exactly at the end of the world, but on its eve. Consequently these ceremonies are preparatory in nature and are directed especially towards women. Hallelujah must be learnt and performed by all peoples, including non-Indians. But women must always engage in a long period of apprenticeship.

Forewarnings of the destruction of the earth are seen in various elements, such as newborns with birth defects, shorter days, terrestrial deformations, people’s height, aging, illnesses and death. On this point, people day that the length of the day is slowly decreasing since the sun is moving ever more quickly across the sky, making the weeks ever shorter. Concomitantly, individuals themselves are becoming gradually but inexorably îpun umadî, ‘diminished people’: each generation individuals are born who are, according to Kapon cataclysmology, physically shorter than the previous generation. Moreover they are people who have been reduced to pure automatons, îpun pîra, “without their own will.” They also claim that the aging process is gradually accelerating, making individuals born not so long ago too old, and that diseases are also on the increase. Finally, they assert that large terrestrial deformations have been seen in the form of deep craters. But it is in the cities that these signs are more numerous and perceptible.

Hallelujah sings not so much of the agents of destruction but of the various beings and instruments that will descend from the sky and, once on earth, will lead, support and accompany the ascension of all those taking part in the ritual. The Ingarikó say without exaggeration that the sky will come down. The two most important beings in this descent are a bench of light and the shadows of the fathers and mothers of natural entities, the indjerî. The bench of light is a messiah who speaks a special, inaudible language. He will teach this language and transport people to the sky. He is known as wise one (epukena), older brother (ui), son of my father (papay mumu), or by his proper name, sisosikray (sixoxikrey) or kîray, Jesus Christ or simply Christ.

On the terrestrial level all the participants will undergo the first change of skin, which leads to their radical transformation into shadows of the fathers and mothers of natural entities. The person is no longer human but indjerî. The second change of skin, the most important and experienced by everyone only on the celestial level, is initially announced in a supplication made to the bench of light, recited during the Hallelujah, through the expression îmîrî-pe wetope, for I to become equal to you, like you. The fragment îmîrî-pe, like you, equal to you, also appears in the prayers. This transformation is also expressed by the forms epukena-pe, like a wise person, and yapon-pe, like a bench, which also figure in the songs. In addition it also appears in the maximal form, sixoxikrey yurî, Jesus Christ I. This is chanted about ninety times consecutively, or almost, while the simultaneous dance movement corresponds to the high point of the ceremony in which one pair emerges and turns in the opposite direction to the column formed by all the other dancers, moving either clockwise or anti-clockwise until they rejoin the group. The first pair always includes the master-of-ceremonies (ina epuru). Consequently the bench is the messiah and the ulterior form of the transformation produced by Hallelujah.

Simultaneously the change of language is made. People start to speak the language of the messiah bench, inaudible until then. All the indications are that it was the prior and fundamental conception of a special language which had to be learnt that enabled and governed the incorporation of foreign words into Kapon cosmology, whether in the songs or elsewhere. In this sense, the missionaries offered a privileged nomenclature for a cosmological portion that consisting of a domain separate from experience, radically different and almost completely unknown, kept open the possibilities of absorbing from the outside.

Today dome descents can be seen. Books fall from the sky, or in other terms, some benches of words have already been thrown to earth. The Kapon say that the papers of books are “the bench of words,” mayin apon (word bench). They conceive, therefore, a close connection between paper and bench. We can state, then, that the hermetic question of the Kapon fascination and demand for papers is a particular case of the relevance that the figure of the bench possesses in their cosmology. Hence the literal launch of papers and books involves the descent of benches, something that is more apparent on the eve of the terrestrial annihilation. Indeed, these are complementary benches given that the books can be seen but do not speak by themselves and that messianic bench cannot be observed, only heard.

Among the peoples neighbouring the Kapon, we can observe a variety of benches, either used in the domestic sphere, in welcoming ceremonies, in rock paintings, in the paraphernalia of chiefs and shamans, in the toponymy or in mythology. There are various associations between, on one hand, the bench and, on the other, constellations, mountain ranges, waterfalls and animals. Advancing into Venezuelan territory, the mountain range close to the Caroni rive is conceived by the Pemon as a succession of benches of a giant anthropomorphic eagle. Meanwhile on the Uraricuera river, below Maracá island, a large rock found there is, according to the Pemon, the bench of the father of the macaws, watoima-mureyi, and further to the north, the Serra do Banco, a name adopted by Brazilian maps, is the bench muiritêpê abandoned by a mythic shaman of the Pemon. The benches are above all linked to the posthumous destiny of the shamans.

Parixara

Aleluia is the main ritual of the Ingarikó, but parixara, celebrating the harvest, is one of the group’s most traditional festivals. Sometimes when parixara is danced during festivities for the December harvest a number of separate events may be combined.

One event that is being seldom practiced by the group is after the hunting trip, the moment when parixara is held. The akamana hunters, who have been absent from the community for 15 days, are welcomed by the women. Laden with caxiri (fermented manioc drink) the women walk through the dense forest to meet their husbands. Everyone arrives in the village singing and dancing, next more caxiri is served and the game is later divided up among all the families. The various events that happened during the hunt are narrated at any time after the arrival of the hunters. Parixara may be begun immediately and generally only ends when the caxiri runs out.

Productive activities

The domestic groups comprise basic, relatively independent productive units, each one working in its own area of crops. They practice slash-burn agriculture in which the clearing and burning of the forest is undertaken collectively by various domestic groups, while planting, weeding and harvesting are carried out by each family.

Women assume a predominant role in the tasks of harvesting and preparing food. They are exclusively responsible for making caxiri and pajuaru, fermented manioc drinks, basic components of the daily diet and of community rituals. They dedicate themselves mainly to village life, the tasks of spinning and weaving cotton, among other work, while the men are more concerned with activities relating to economic exploration outside the village, undertaking routine hunting, fishing and gathering expeditions along the rivers and in the forests, far beyond the boundaries of the respective villages.

Relations with the other peoples of the Mount Roraima region takes place through trade exchanges – for which they undertake expeditions – marriages and the periodical organization of festivals where they dance above all Hallelujah.

The dynamic of Ingarikó social life consists of fairly diversified relations in terms of rhythm and intensity. These relations, considered as a whole, alter significantly over the annual cycle of community activities determined by climate variations and by the composition of soils in specific areas. Both factors play a major role in determining the occupation sites and distribution of the indigenous population, as well as improvements in the specialized strategies for managing resources.

Gathering activities, for their part, involve a series of locally diversified and specialized procedures. These procedures are undertaken during particular moments of the growth and reproduction of flora and fauna throughout the year, though in an alternated form.

Hunting during the transition between seasons is ideally pursued in the forest areas, while becoming confined during the dry season to the areas close to rivers and lakes.

(Text based on the publications Pemongon Patá: Território Macuxi, rotas de conflito (2001) and Os Taurepáng: memória e profetismo do século XX (1993), by Paulo Santilli and Geraldo Andrello respectively)

Diet

The Ingarikó, like many other South American groups, consume manic bread (eki) as the main staple food in their diet. There are two other components in addition to the bread: caxiri made from sweet potato (sakï), and a regional speciality, damorida, pepper broth (pïmëi) mixed with various ingredients, especially meat and fish. Caxiri is, in fact, the element to which the widest range of other foods are added, including caxiri with maize, banana, sugar cane or pumpkin. Both bread and caxiri require the woman – solely responsible for their production – to possess a technological knowhow that spans from extracting the poison from manioc to the reuse of the latter when it is transformed into the delicious tucupi sauce, widely used in Amazonian cooking.

Smoked game, though now passing through a phase of scarcity due to the growth of the population over the last 10 years, is much appreciated by everyone. Fish and crustaceans are more rare in the Ingarikó diet since the cold mountain waters and the low levels of oxygen in the rivers comprise adverse conditions for many species.

Banana is the most predominant fruit crop, followed by pineapple, oranges, tangerines, mangos and sugar apple, with each type of fruit being planted and monitored by a different nuclear family – a practice that sustains the relation of exchange between them. Depending on the season of the year, other food may be available. For example, in summer ants, lizards, fruit and honey may be added to the diet. The only restriction in terms of eating meat is eating jaguar, kaikusi, avoided by older people though the younger generation no longer adhere to this rule.

(Maria Odileiz Sousa Cruz)

Arts

A group’s material culture can be identified by sets of technologies and objects that express its modus vivendi, for example: painting, utensils, adornments, tools and containers, many of which can be perfected over time. Undoubtedly these and other elements symbolize and collectively represent the material culture, both in different time periods and across diverse cultures, since some of these elements are determined by the choices made by the artisan over during the course of his or her life. Listed below, therefore, are some elements of Ingarikó material culture, artefacts governed in principle by the group’s social, artistic and economic life. It is worth remembering that material objects can seldom be disconnected from the group’s cosmological viewpoint.

Basketry

Basket weaving is one of the most expressive elements of Ingarikó culture. Beautiful baskets from vine and arumã fibre with a variety of woven designs are made by men and have multiple functions. As well as the combination of colours, forms and sizes, the material is further enriched when iconographic shapes are added.

There is also the exquisite vine hat, a traditional type of sandal, pïta pi'pï, mo'mo necklaces and pakara and taimé bags. The last two artefacts can be made by women but their production tends to involve very small items. The Ingarikó seem to hold the notion that the best artisans are men and thus women are assigned a secondary role in this activity.

Artefacts used in fishing

One important item is the canoe along with its set of paddles. These items are highly disputed in the regional trade network; the Ingarikó canoes are acquired by other groups, such as the Makuxi, since they are recognized as the best of the region. The canoe can be traded for cattle and horses, for example, or be sold.

Along with various basketry artefacts (jiki moroi', jamaxim ma'wai pïruta, the manari sieve) that are also used in fishing activities, nets of various sizes are employed, and nets and slings are woven from different raw material. A set of arrows used in fishing is covered in decorations with featherwork and paint designs on the tips.

Art and hunting

Body tattooing (forearms tattooed with vertical lines and the thorax with horizontal lines) is a form of invoking the spirits who protect the hunters and of attracting abundant game. The hunters typically revitalize their tattoos by deepening the cuts in the body and then spreading ginger over the wounds and in their nostrils. War clubs, wooden spears, and large bows and arrows are the main instruments used by men in hunting, though the arakapusa gun is a tool familiar to the group for a long time. As well as the instruments and supplies taken by the hunters on the expeditions, they also take a calendar – a length or fibre or rope with 15 knots, leaving a replica with the family.

Iconography and kansu tattoos

The region inhabited by the Ingarikó contains rock paintings that indicate the antiquity of the human presence there. Unfortunately, the absence of archaeological studies forms a lacuna in terms of understanding the region’s formation and occupation. On the other hand, in contemporary terms, almost all the artefacts, baskets, traditional utensils, clothing and adornments possess iconographic representations of the different worlds with that of animals being preferred.

The kansu tattoos are also examples of contemporary iconography. Young women after their first menstruation can be tattooed on their face with vertical lines (on the lower part of the jaw and the upper mouth), thereby displaying their beauty and above all their ability to make good caxiri and large manioc bread.

The main raw material used for tattooing is genipap, though resins from other plants may also be used.

Notes on the sources

Without a shadow of doubt, Guiana concentrates the most voluminous and diverse source of information on the Ingarikó (Akawaio and Patamona). These include records made in the field since the 19th century by missionaries, naturalists, Indian inspectors, museum curators, miners, historians, linguists and anthropologists. They have examined in particular prophetism and the Hallelujah ritual. One of the first key contributions is the work of Anglican missionary William Brett. Among the anthropologists, Audrey Butt Colson has dedicated herself for five decades mainly to the study of cosmology and the exchange system. The various scattered records were assembled, presented and analyzed by the anthropologist Stela Abreu in her MA dissertation, subsequently published. This work also includes the first ethnography of the Hallelujah ritual among the Ingarikó on the Brazilian side, produced in 1993. In 1999 the linguist Odileiz Sousa Cruz began researching the Ingarikó language in Brazil, concluding his Ph.D. thesis in 2005.

Sources of information

- ABREU, Stela Azevedo de. Aleluia: o banco de luz. Campinas: Unicamp, 1995. 132 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- --------. Aleluia e o banco de luz. Centro de Memória Unicamp, Campinas, 2005, 132p.

- AMODIO, Emanuele & PIRA, Vicente. "Ingarikó". In: CEDI (Centro de Documentação e Informação). Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Volume 2 - Roraima (manuscrito). São Paulo, 1983.

- ANDRELLO, Geraldo. Os Taurepáng: memória e profetismo do século XX. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 1993. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- BRETT, William. 1868. The Indian Tribes of Guiana: Their Conditions and Habits London: Bell and Daly Publishers.

- --------. Legends and Myths of the Aboriginal Indians of British Guiana, London, 1880

http://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/sa/lmbg/index.htm

- --------. s/d. Mission work among the Indian tribes in the forest of Guiana. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- BUTT-COLSON, Audrey. "The Birth of a Religion: the origins of a semi-Christian Religion among the Akawaio". In: J.Middleton (ed.), Gods & Rituals: Readings in Religious Beliefs & Practices. The Natural History Press, New York. [1960]1967.

- ---------, “Akawaio”. IN: World Culture Encyclopedia.

http://www.everyculture.com/South-America/Akawaio.html

- --------- "Inter-tribal Trade in the Guiana Highlands". In: Antropologica 34: 1-70, 1973.

- --------. "The Spatial Component in the Political Structure of the Carib Speakers of the Guiana Highlands: Kapon and Pemon", Antropologica 59-62: 74-124, 1983.

- --------. Fr. Cary-Elwes S. J. and the Alleluia Indians. Amerindian Research Unit: University of Guyana, 1998.

- --------- "´God´s Folk´: The evangelization of Amerindians in western Guiana and the Enthusiastic Movement of 1756". Antropologica 86.1994-1996. pp-3-111.

- CARY-ELWES, Cuthbert [1909-1923]1985 Rupununi Mission. Londres, Jesuit Mission.

- CAULIN, Antonio 1841[1779] Historia corográfica. Caracas: G.Coser.

- CENTRO DE INFORMAÇÃO DIOCESE DE RORAIMA. Índios de Roraima. 1989.106p.

- CONSELHO INDÍGENA DE RORAIMA. Raposa Serra do Sol: os índios no futuro de Roraima. Boa Vista: CIR, 1993, 40 p.

- --------; COMISSÃO PRÓ-ÍNDIO-SP. Parecer sobre o relatório de impacto ambiental da hidroelétrica de Cotingo. São Paulo: CPI, 1994. 37 p.

- COSTA, Kinha. 1999. Índio Ingaricó visita Amsterdã. In: Revista Papagaio, n. 35 junho-julho, pp. 13 e 29. Amsterdam: Fundação Encontro.

- CRUZ, Maria Odileiz Sousa. "A Posse do Nome em Ingarikó (Caríb)". In: Atlas do I Encontro Internacional do Grupo de Trabalho sobre Línguas Indígenas da ANPOL. Ana S. A. C. Cabral e Arion D. Rodrigues. (eds.). Tomo II: 13-21. Belém: UFPA, 2002.

- --------. Fonologia e Gramática Ingarikó - Kapon Brasil. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2005. (Tese de Doutorado)

- COUDREAU, H. A. La France Equinoxiale, II: Voyage à travers les Guyanes et L'Amazonie. Paris, 1887.

- EDWARDS, Walter F. "A Brief History of the Amerindians of Guyana". In: Publication of papers presented at the conference of The Society for Caribbean Linguistics. Cave Hill, Barbados: University of the West Indies, 1978.

- --------. An Introduction to the Akawaio and Arekuna Peoples. Amerindian Languages Project. Guyana: University of Guyana, 1977.

- FARAGE, Nádia. As muralhas dos sertões: os povos indígenas no Rio Branco e a colonização. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra/Anpocs. 1991.

- FARRAR, Thomas. Notes on the History of the Church in Guiana. [New Amsterdam] Berbice, W.Macdonald, 1892.

- FORTE, Janette. "The Populations of Guyanese Ameridian Settlements in the 1980s". In: Occasional Publications of the Ameridian Research Unit. University of Guyana. Georgetown, 1990.

- --------. About Guyanese Amerindians. Georgetown, BusinessPrint, 1996.

- --------. Thinking about Amerindians. Georgetown, BusinessPrint, 1996.

- --------. Amerindian languages of Guyana. In: As línguas amazônicas hoje. F. Queixalós & O. Reanult-Lescure (orgs.). São Paulo: Instituto Socioamabiental, 2000, pp.317-331.

- FRANK, Erwin. "A construção do espaço étnico roraimense, ou: Taurepáng existem mesmo?" In: Revista de antropologia, São Paulo, 2002, vol. 45 e n. 2.

- FUNDAÇÃO NACIONAL DO ÍNDIO (FUNAI). "Grupo Ingarikó vê branco pela primeira vez". In: Revista Atualidade Indígena. Ano II, n. 10. Brasília. (Maio-Jun.), 1978.

- Grupos Étnicos Indígenas en Venezuela.

http://www.pmi-usa.org/paises/Aup2/presenta/Etnias%20Latinas/Venezolanas.htm

- HENFREY, Colin. The Gentle People: A Journey Among the Indian Tribes of Guiana. London: Hutchiwson & Co, 1964.

- HILHOUSE, William. Indian Notices. Georgetown, 1825.

- HOMET, Marcel F. Os Filhos do Sol. São Paulo: Instituição brasileira de difusão cultural S. A. (Trad. Beatriz Sylvia Romero Porchat),1959. Título original em Alemão Die Söhne der Sonne. Olten: Verlag. Otto Walter Ag. 1958.

- IM THURN, E. Among the Indians of Guiana. New York: Dover Publications, 1883.

- KENSWIL, Frederick W. Children of the Silence: an account of the aboriginal Indians of the upper Mazaruni River, British Guiana. Georgetown: Interior Development Community,1946.

- KEYMIS, Laurence "A relation of the second Voyage to Guiana, performed and written in the year 1596". In: Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations of the English Nation. Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons. 1904. Vol 10. pp. 441-501.

- KOCH-GRÜNBERG, Theodor. Del Roraima al Orinoco. 3 vols. Caracas: Banco Central de Venezuela. [1917-24] 1979-82.

- --------. Do Roraima ao Orinoco: observações de uma viagem pelo norte do Brasil e pela Venezuela durante os anos de 1911 a 1913. São Paulo: Editora Unesp/Instituto Martius Staden. 2006. vol. 1.

- --------. A distribuição dos povos entre rio Branco, Orinoco, rio Negro e Yapurá. Manaus: Editora INPA/EDUA, 2006.

- LORIMER, Joyce. English and Irish settlement on the river Amazon, 1550-1646. The Hakluyt Society, London, 1989.

- MIGLIAZZA, Ernest C. "Languages of the Orinoco - Amazon Region: Current Status". In: South American Indian Languages: Retrospect and Prospect. Harriet E. M. Klein and Louisa R. Stark (eds.). Austin: University of Texas Press. 1985, pp. 286-303.

- MLYNARZ, Ricardo Burg. Processos Participativos em Comunidade Indígena: um estudo sobre a ação política dos Ingarikó face à conservação ambiental do Parque Nacional do Monte Roraima. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2008. (Dissertação de Mestrado).

- MOSONYI, Esteban. "Indian Groups in Venezuela". In: W.Dostal. The Situation of the Indian in South America. 1972.

- NATIONAL FOUNDATION HEALTH-FNS. Relatório sobre a Área Ingaricó. Boa Vista - Roraima. 1994, Ms.

- NUNES PEREIRA, Manoel. Moronguetá: um Decameron Indígena. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. 1967, vol. 1.

- SANTILLI, P. As fronteiras da república: história e política entre os Macuxi no vale do rio Branco. São Paulo, NHII-USP/FAPESP, 1994.

- --------. Pemongon Patá: Território Macuxi, rotas de conflito. São Paulo: Unesp, 2001. 227 p.

- SCHOMBURGK, R.H. "Travels in Guiana and on the Orinoco during the years 1835-39". In: W. E. Roth. The Argosy. Co. Ltd., Georgetown: British Guiana.

- --------. A Distribution of British Guiana. London, Simpkin, Marshall & Co, 1840.

- SAMPAIO SILVA, Orlando. "Os grupos tribais do território de Roraima". Revista de Antropologia 23. 1980. pp. 69-89.

- STAATS, Susan. "Fighting in a Differente Way: Indigenous Resistance through the Alleluia Religion of Guyana". In: Jonathan Hill (ed.), History, Power, and Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Americas 1492-1992. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. 1996, pp.161-179.

- SCHOMBURGK, R.H. "On the Natives of Guiana". Journal of the Ethnological Society. Pp.253-276. 1848a.

- --------- "Remarks to accompany a comparative vocabulary of eighteen languages and dialects of Indian tribes inhabiting Guiana". Simmond´s Colonial Magazine 15:46-64. 1848b.

- ----------Travels in Guiana and Orinoco in the years 1835-1839. Georgetown: The Argosy Company. 1931.

- SWAN, Michel. The Marches of El-Dorado: British Guiana, Brazil, Venezuela. London, Jonathan Cape, 1958.

- THOMAS, David. "El movimiento religioso de San Miguel entre los Pemon". Antropologica, 43: 3-52. 1976.

- TRINDADE, Amilton. Índios Ingaricós. In: Revista Ecologia e desenvolvimento. Rio de Janeiro: Terceiro Mundo. 1994, ano 2, n. 36.

- ULE, Ernst. "Entre os índios do rio Branco do Norte do Brasil." IN: T. Koch-Grünberg, A distribuição dos povos entre rio Branco, Orinoco, rio Negro e Yapurá. Manaus: Editora INPA/EDUA, 2006 [1913], pp.113-151.

- UNDP (Guyana) National Report on Indigenous Peoples and Development. http://www.sdnp.org.gy/undp-docs/nripd/

- WHITEHEAD Neil. L. The Patamona of Paramakatoi and the Yawong valley: an oral history. Guyana: The Hamburg Register Walter Roth Museum of Antropology Georgetown, 1996.

- --------. . Dark Shamans. Kanaimà and the Poetics of Violent Death. Durham & London: Duke University Press. 2002.

- --------. "Three Patamuna Trees: Landscape and History in the Guyana Highlands". Histories and Historicities in Amazonia. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. 2003, pp.59-77.